Le Mans 24 Hours returns after 10-year hiatus with plenty of incident

It may have taken a full decade and immense manpower to get the race back on, but the return of the Le Mans 24 Hours brought plenty of incident, and we were there...

Getty Images

Before the war Le Mans was a household word in British motor racing circles, as well it might be, with British cars winning this gruelling 24-hour sports car race outright on six occasions. The Germans did much damage to the famous circuit during the war and only this year has the Automobile Club de l’Ouest been able to revive this classic of sports car classics.

As soon as it was announced that the race would be held entries began to pour in, and the list closed at 52, of which 15 hailed from this country, 33 from France, one from Italy, two from Czechoslovakia, and one from Belgium. Apart from those racing to qualify for next year’s event, there were three distinct races: the Grand Prix d’Endurance, divided into the usual capacity classes and a mere matter of going as far as possible in the 24 hours between 4pm on June 25 and 4pm on June 26; the Biennial Rudge-Whitworth Cup race, for which the entrant has to qualify the first year by his car finishing (in this case in the 1939 race), and then contests the car afresh the next year; and the Annual Cup race, decided on a formula based on mileage covered balanced against engine size.

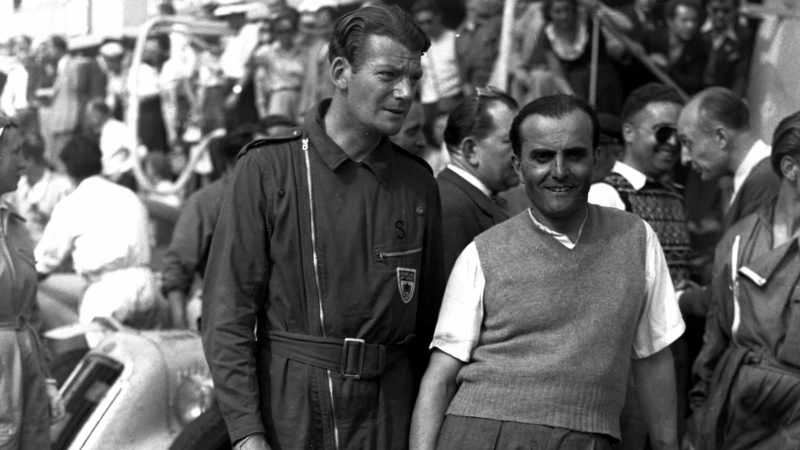

Peter Mitchell-Thomson and Luigi Chinetti. Chinetti drove for 22 hours as Lord Selsdon was unwell, something many believe was self inflicted over race week

In 1939, the last year until last month that the race was run, Wimille and Veyron’s 3.3-litre Type 57SC Bugatti won outright at 86.35mph, Gordini and Scaron’s FIAT taking the Biennial Cup. The lap record stood to the credit of Robert Mazaud’s 3.6-litre Delahaye, at 96.7mph.

The course measures 8.68 miles (14 kilometres) and skirts the town of Le Mans. From the pits and tribunes the course runs towards the right-angle at Tetre Rouge, along the main Le Mans – Tours road, curving right-handed into Mulsanne straight, past the Café de l’Hippodrome to Mulsanne corner. So drivers come to the left-handed corner at Arnage, near the aerodrome where British visitors land, and then the road twists and wriggles to the notorious White House corner and so back to the start.

As usual the races are strictly for sports cars, but this time bona fide ‘prototypes’ were allowed to race with the catalogued models, as the organisers did not wish to hamper post-war developments. The usual regulations that so make the atmosphere of this great race were enforced. Repairs could only be carried out with the aid of spares and tools carried in the cars and then only by one assistant besides the driver. Fuel tanks were sealed and refuelling permitted only after 25 laps had elapsed since the start or a previous refuel, calling for a range of 210 miles. Proper precautions were called for to ensure that headlamps wouldn’t extinguish themselves as one motored at full lick through the short (but inky) summer night. And so on and so forth — so that the atmosphere was almost that of the great days of our Bentley triumphs.

From an early hour people streamed to Le Mans, where the atmosphere is quite unique. Gay flags floated in the breeze above the roof balcony of the magnificent new concrete pits and, opposite, vast concrete stands accommodated keen and critical crowds such as only France can produce. The sun shone from a torrid sky, so that the tar became sticky on the roads and the coloured equipe vans behind the pits glinted colourfully in the strong light, while, behind, the green of the woods and fields formed a backcloth to the memorable scene. With the crowds picnicking all around the course, the loud bands, the scantily-garbed girls in the depots, and aircraft arriving at Le Mans airfield, all the ingredients of a first-class Continental motor-race were present in full measure.

Safety arrangements were excellent, with a sand-wall and fence before the tribunes and fencing and barbed-wire at the corners. The whole tribune area was well-policed and Pressmen were handsomely looked after in their lofty and extensive Press stand, where they sat at school-desks and received food boxes and wine tickets at generous intervals. Walking along the rows of competing cars we noted that Grignard’s Delahaye had a headrest and cowled-in radiator, and the names of its drivers on the scuttle, while Villeneuve (Delahaye) was one of those who co-opted Robert Bosch, to see where he was, at night. Rosier’s Talbot had double cushions as a back-rest, a small flat headrest and its spare wheel horizontal in the tail. The Ecurie France Talbot had a 16-coil cooler protruding from its scuttle, a power bulge along the off-side of the bonnet and small, but quick-action, fillers. The Delage cars had 6in ‘funnels’ to facilitate pouring oil into their valve-cover oil fillers. Culpan sported an RAF roundel on his Frazer Nash, which had a fabric cover over the spare wheel. Eggen’s Alvis was an all-enclosed two-seater with vast boot, and Hay’s Bentley saloon had the fuel tank behind the rear seat, a filler protruding from each panel of the rear window, a thermos clipped to the rear of the front passenger’s seat, and 6.50-19 Dunlop racing tyres on its spatted rear wheels. A mechanic was adjusting its tappets.

Eugène Chaboud aboard the Delahaye he shared with Charles Pozzi. A winner in 1938, he would fail to finish any of his three post-war entries at Le Mans

Getty Images

A hush fell as the drivers lined up opposite their cars and Charles Faroux instructed the timekeeper to raise the tricolour. As it swept down the line of men broke and, in what seemed a moment, Chaboud’s Delahaye, a vicious two-seater with vast aerodynamic wings, swept off in the lead, followed by Paul Vallée’s Talbot, which overtook Hay’s Rolls-Bentley as it got away. Next came Rosier (Talbot), Grignard (Delahaye), Veuillet’s Delage, Johnson in the 2-litre Aston-Martin, Chinetti’s Ferrari, Dreyfus’ Ferrari, and Leblanc’s Delahaye. Slow to move off were Villeneuve’s Delahaye and Walker’s Delahaye driven by Tony Rolt. Hémard had to ease his Monopole out to clear Flahault’s stationary Delahaye, while the Singer and Fairman’s HRG were very hesitant and poor Jack Bartlett in the Healey saloon didn’t get off until the car had been rocked to unglue the starter and then pushed, some three minutes being lost thereby.

After a while the pack came winding downhill to pass the tribunes at the end of lap one, and the order was: Chaboud (Delahaye), comfortably ahead of Rosier (Talbot), then a vast gap before Vallée (Talbot), Grignard (Delahaye), Johnson (2 1/2-litre Aston-Martin), Veuillet (Delage), Dreyfus (Ferrari), Chinetti (Ferrari), Louveau (Delage), Rolt (Delahaye), Villeneuve (Delahaye), Culpan (Frazer Nash) and the rest.

Another lap and Dreyfus was fourth, with Chinetti in the other Ferrari coming up to pass Vallée’s Talbot. After three laps the leaders were Chaboud, Rosier and Grignard, while Dreyfus had dropped back behind Chinetti and Vallée. Then came a minor excitement, for Chaboud was seen to have damaged his off-side rear wing, which was tilted at a queer angle. Some time later Rosier had a lengthy stop, then Peter Clark passed the pits with his helmet off and the HRG did not reappear — the cooling radiator was hors de combat, the header-tank connection having pulled away.

— At 6pm the leaders were —

1st: Chaboud (Delahaye), 22 laps, 1hr 59min 59.7sec

2nd: Flahault (Delahaye), 21 laps, 1hr 56min 32.2sec

3rd: Chinetti (Ferrari), 21 laps, 1hr 58min 34.1sec

At 8pm the order was still Delahaye, Delahaye, Ferrari. At 8pm Grignard’s Delage ran out of fuel just short of its pit and the driver was deservedly clapped as he pushed the car the remaining distance — French crowds are like that. Calmly he grabbed the chock to place beneath a rear wheel, before refuelling. Alas, 14 minutes were lost before petrol could be got through to the carburetters. No time was wasted when Pozzi relieved Chaboud of the leading Delahaye.

The situation now became dramatic, as race situations will. Chinetti lost 7.5 minutes at his pit, resuming just as the other Ferrari appeared in sight, and at the same time Flahault’s Delahaye commenced a series of pitstops, the engine reluctant to restart, so that 43.5 minutes were lost, the symptoms suggesting slipped timing. And, as if that wasn’t enough, Pozzi in the leading Delahaye caught fire at Mulsanne, and it must have been half-an-hour before, amid a feverish ovation, he coaxed his stricken car to the pits, in the dusk sans lights! Then Dreyfus came in to refuel, overshot his depot, jumped out, and nimbly rolled his car back.

Luigi Chinetti guides his Ferrari 166MM through Tertre Rouge on the way to a very important win

— At 9pm the positions were —

1st: Dreyfus (Ferrari), 52 laps, 4hr 50min 27.3sec (87.4mph)

2nd: Flahault/Simon (Delahaye), 51 laps, 4hr 45min 49.0sec

3rd: Chinetti (Ferrari), 51 laps, 4hr 59min 22.3sec

The Healey had another brief stop about this time, the Chaboud/Pozzi Delahaye got going again after 11 minutes, but came in a lap later with the bonnet open on the off side, and went off again, only to disappear for an appreciable time ‘out in the country.’ The Flahault Delahaye was also in dire trouble, and then the loudspeakers — which were in efficient action almost without cessation throughout the 24 hours — told us that Dreyfus had overturned, without injury, at White House corner. It was just getting dark and this may have resulted in a misjudgement as he went to overtake a larger car. The whole aspect of the race naturally changed, Paul Vallée’s Talbot now leading Veuillet’s Delage, with Selsdon’s Ferrari, Chinetti driving, pressing them hard.

— At 10pm the positions were —

1st: Vallée/Mairesse (Talbot), 61 laps, 5hr 50min 10.2sec (84.13 mph)

2nd: Selsdon (Ferrari), 61 laps, 5hr 50min 25.7sec

3rd: Veuillet/Mouche (Delage), 60 laps, 5hr 56min 57.5sec

By 3am Gérard’s Delage was second to Louveau’s, having caught the Frazer Nash, while Selsdon led. Louveau was being regularly signalled by a torch shining on a number board. At 4am the Ferrari had a three-lap lead and the Maréchal/Mathieson Aston-Martin was fifth, three laps behind the Frazer Nash. A ‘to let’ sign had now appeared before Rolt’s pit, where they had packed up and gone.

The crowd on the balcony clapped — at 4.26am! — as Selsdon took over the leading Ferrari from Chinetti, who had driven the car continuously up to this point. The engine fired after the starter had spun for what seemed an age. The Bouchard Delahaye resumed its repeated pit-calls, but loud claps greeted the refuelling of the Flahault/Simon Delahaye, now fully recovered, but back to 11th place. Grignard’s Delahaye was reluctant to restart and more than one man worked on it.

The Delahaye 135CS of Jean Brault and Henry Leblanc gets a top-up in the pits

Getty Images

— The positions at 6am were —

1st: Selsdon/Chinetti (Ferrari), 139 laps, 83.4mph

2nd: Louveau/Jover (Delage), 137 laps

3rd: Gérard/Godia-Fales (Delage), 137 laps

Moreover, the Delage was catching the Ferrari at the rate of about 6.5sec a lap, and Louveau passed just as Selsdon had another brief stop. The Frazer Nash was now fourth and the Chaboud Delahaye fifth. Incidentally, as the sun’s warmth returned again, at 6.45am, 27 cars were still running.

The Gérard Delage came in for fuel, shock-absorber adjustment and change of driver at 7.30am, but was away in 2.5 minutes. Chaboud was a visitor shortly afterwards, the spectators again clapping a very gallant drive following early adversity; the radiator tended to steam as he motored off. Next, much smoke when Bouchard’s Delahaye came in with its near-side rear brake on fire. At 7am the Ferrari had done 149 laps to Louveau’s 148, Gerard was also on his 148th, the Frazer Nash on its 144th, but the unlucky Chaboud Delahaye had done only 140. With the return of daylight the race average had leapt up to nearly 90mph.

So the race went on, with routine pit-stops and some having no semblance of routine. The slower cars that had not done their qualifying distance were flagged-off, Phillips’ MG receiving the black flag. Momentarily, a larger car was baulked by Mahé’s amazing little saloon Simca, but the latter drew away from its rival round the curve beyond the pits, and the Ferrari swerved and skidded in avoiding Morel’s Talbot saloon as it drew out of the pit. The unhappy Flahault/Simon Delahaye, which had received such a brisk reception from the crowd, was pushed to the dead car park at 10.44am.

Cue drama! Louveau brought the Delage in in dire trouble, but went on. Shortly afterwards Chinetti was stationary at his pit, with Louveau in again. On his first stop the plugs had been replaced, water added, and the rear wheels changed, so we knew, now, that something more serious was amiss. The work was good, calm, but half-an-hour was lost while extensive work was done on the engine, concluding with more new plugs — as with Gérard’s Delage, too much oil seemed to be getting “upstairs”.

The Ferrari left first, but it, too, lost much time, work apparently being done on the front of the chassis, necessitating attempted removal of a headlamp. Meanwhile, the Frazer Nash motored nearer to victory. It certainly wasn’t Delage’s day, for soon after those intense moments involving Louveau and Chinetti, Veuillet had a short stop — for a moment no one saw him come in, in the concentration on Louveau’s car — which produced much Gallic shouting!

Chinetti now began to make occasional stops at his pit, presumably because he had such an excellent lead. Louveau remained second, in spite of another stop, but the Frazer Nash, apart from slowing for a while due to a fuel vapour-lock, was going well, needing no water, although for much of the time Aldington drove, because the clutch refused to free, so that clutchless gear-changes were essential. Even this trouble finally rectified itself, and this new British car remained a splendid third.

Alas, just as we hoped to see Maréchal press for this third place, it was reported at 1.05pm that the Aston-Martin saloon had overturned at White House Corner, Pierre being seriously hurt [he would succumb to his injuries the next day]. His brakes had, it seems, been absent for many laps.

Claps greeted another pit departure, on the part of the Delage, but the leader’s position held without change — Ferrari, Delage, Frazer Nash. Hot cars came in and were reluctant to restart, but still the order held. Grignard’s Delahaye, in particular, consumed vast quantities of both time and amps, oil as well as smoke began to appear from Gérard’s Delage, and Veuillet’s Delage stopped frequently, while Bouchard had clouted a hazard with the off-side front of his car. Yet bravely the men struggled to keep the cars going, and the onlookers — now 200,000 strong — showed knowledgeable approval, as they pressed closer to the rails in anticipation of the arrival of the President of the Republic. He came in a fine Renault escorted by many transverse-twin motor-bicycles and a fwd Citroën, to honour the first post-war Le Mans.

Then, as suddenly as it had begun, this great race ended, Chinetti victor for Italy in Lord Selsdon’s 2-litre V12 Ferrari. The Louveau Delage was second, in spite of many setbacks, while Aldington and Culpan very creditably brought the ‘High Speed’ Frazer Nash ‘Competition’ two-seater home third. The Talbot saloon finished fourth, frantically waved down on its last laps and missing from the parade d’honnear, and Gérard’s Delage struggled into fifth position. The Thompson/Fairman H.R.G. won the 1.5-litre class for Britain.

Originally published in Motor Sport, July 1949