Chapter 3: Stirling Moss' dominance in sports cars and GTs

Sports cars, saloons, GTs, Moss mastered the lot – and it could be argued that he was better in these than in a grand prix racer

His family’s BMW 328 – the finest 2-litre sports car of its pre-war generation – provided the stepping-off point in March 1947, a hirsute and helmetless Moss carrying off a pot in a trial carrying the family’s name. It was the start of a long affair. Single-seaters would soon sweep him up – although his first Formula 2 HWM was essentially a sports car with its wings removed – but Moss’s affection for two-seaters never waned. He won in nimble Frazer Nash Le Mans Replica and brake-less OSCA (a remarkable drive at Sebring in 1954); in Jaguar C-type and Lister-Jaguar; in Maserati 300S – another favourite of his – and 450S; and in Aston Martin DB3S, DBR2 and DBR1. Their importance rivalled Formula 1, yet somehow the pressure was off. Much was expected of Moss still, but the increased team element of the bigger races removed some of the mental load. They were his (relative) relaxation and, as a result, he was arguably better in them than he was in a GP car.

He loved their numerous shapes, sizes and guises, and his turning increasingly freelance saw his racing record diversify ever more: front- and rear-engined Maserati ‘Birdcage’; Austin-Healey Sprite and Porsche Spyder. He even deigned to drive Ferraris, albeit privateer examples. It was in svelte 250GT SWB Berlinetti carrying the Scottish colours of long-time friend and entrant Rob Walker that he scored his sixth – while keeping abreast of the race commentary via its in-car radio! – and seventh RAC Tourist Trophy victories. He tested the prototype 250GTO, too, in readiness for 1962 – Enzo had gone out of his way to woo his favourite driver; Moss in turn had driven a hard bargain – but he would never get to race it.

Ferrari, therefore, was the sworn enemy in the main, as Moss strutted his stuff for Jaguar, Maserati and Astons. It was he who registered the first international victory for a disc-braked car (in Wisdom’s C-type at Reims in 1952); who gave Enzo a firm prod with Maserati’s Bologna trident in 1956-57; and who persuaded a reluctant Aston Martin to send a lonesome DBR1/300 to the 1959 Nürburgring 1000km. The latter victory, achieved after co-driver Jack Fairman had manhandled the car from a ditch before handing to a Moss on the verge of packing up and going home, set up an unanticipated world championship bid that Moss should successfully complete by defeating Ferrari at Goodwood’s RAC TT – despite having to switch cars after his original had caught fire during refuelling. The sensational was becoming almost routine.

Moss prepares to take his Aston Martin DBR2 to fourth place in the 1957 Governor’s Trophy at Oakes Field, Nassau. He scored his first Ferrari win at the same Bahamas Speed Week meeting, winning the Nassau Trophy in Temple Buell’s 290 MM

The outstanding sports car driver of his day, however, would never win the Le Mans 24 Hours. He finished second in the Jaguar 1-2 of 1953 and also in an underpowered/overmatched DB3S in 1956. He probably would have prevailed in 1955, with Fangio as his co-driver, had not even those aforementioned acceptable bounds been exceeded by the most devastating accident in all of racing; Mercedes-Benz withdrawing them from the lead, as the rising toll exacted by Pierre Levegh’s explosive crash was beginning to dawn.

In truth, despite its fringing trees and high speeds, Le Mans was never to Moss’ taste, its extended duration tending to outstrip his machinery’s capabilities to run hard throughout. His reputation as a car-breaker was debatable, but for sure he was not a nursemaid by nature. As such, he was often the willing and, if needs be, sacrificial hare drawing unwary rival teams into an unwise early pace. For nobody could charge harder for longer than Moss: three of his four Nürburgring 1000km victories – on a purpose-built ‘road’ circuit hemmed by high hedges – involved overcoming delays. (The other was achieved in heavy rain and thick mist!)

Fifteen years after that debut in the family 328, Moss took part in a three-lap supposed demonstration-turned-bun fight in Minis. Changing times indeed.

And although he would miss the exponential rise of saloon car racing and the golden eras of Gran Turismo and big-banger sports-prototypes, he had played a crucial role in their nascent stories: he had won in the surprisingly capable Jaguar MkVII – bracing against the passenger door with his foot so as not to slide across its bench seat! – in the ruggedly handsome Aston Martin DB4GT, and in both the Cooper Monaco and Lotus Monte Carlo. But it wasn’t all about the winning. Even in the event of a defeat, his participation was always guaranteed to add frisson to a race in the short-term and embed kudos in the long-term.

- In September 1947, Moss drove his father’s Frazer Nash BMW in the Poole Speed Trials at Lytchett Minister, in Dorset. It was one of his very earliest competitive events

- Moss awaits the start of the 1952 Reims Grand Prix, in which he took Tommy Wisdom’s Jaguar C-type to victory – the first major international win for a car fitted with disc brakes

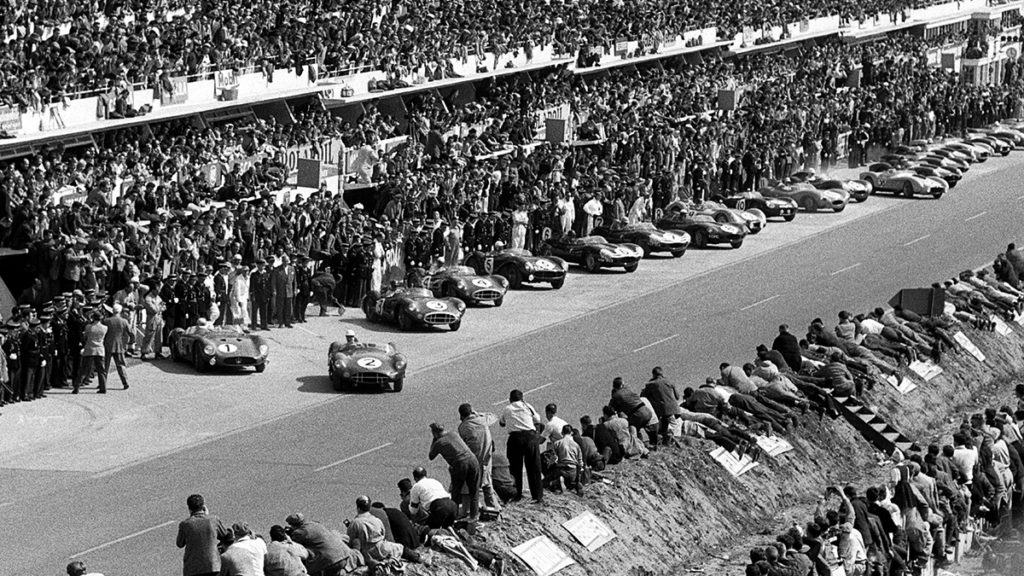

- Further evidence of Moss’ fleetness of foot, as he gets away first following the running start preceding the 1958 Le Mans 24 Hours. He pulled away steadily from the rest of the field and held a huge lead when a broken con rod brought his Aston Martin DBR1 to a halt in the race’s third hour, before co-driver Jack Brabham had taken his first scheduled stint at the wheel. None of the three works Astons lasted the distance

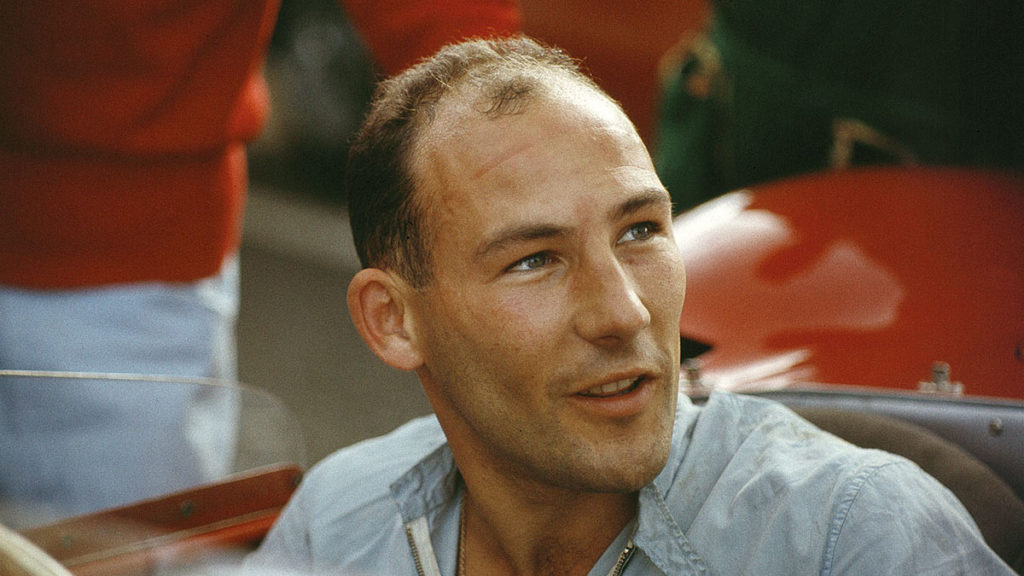

- Relaxed Moss aboard a Maserati 300S, a car that brought him many wins

- Closest to the camera, Moss makes a flying start ahead of the 1952 Goodwood Nine Hours. He was every bit as nimble on his feet as he was at the wheel

- Moss scored his first Nürburgring 1000Kms win in 1956: he and Jean Behra

- Moss in his works Aston DB3S during the 1956 International Trophy meeting at Silverstone, where he finished second to team-mate Roy Salvadori. Note works mechanic Eric Hind with cigarette on the go…

- Moss chats to Jaguar team manager Lofty England during the 1953 Le Mans 24 Hours. He and co-driver Peter Walker finished as runners-up in their C-type, four laps behind team-mates Tony Rolt/Duncan Hamilton (the second of Jaguar’s five victories during the decade), but it was a race Moss would never win

- Moss aboard the Maserati 300S he shared with Harry Schell in the 1957 Sebring 12 Hours. The pair would ultimately finish second to the newer 450S of Juan Manuel Fangio and Jean Behra, both Maseratis doing enough to hold back the leading Jaguar D-type of Mike Hawthorn and Ivor Bueb

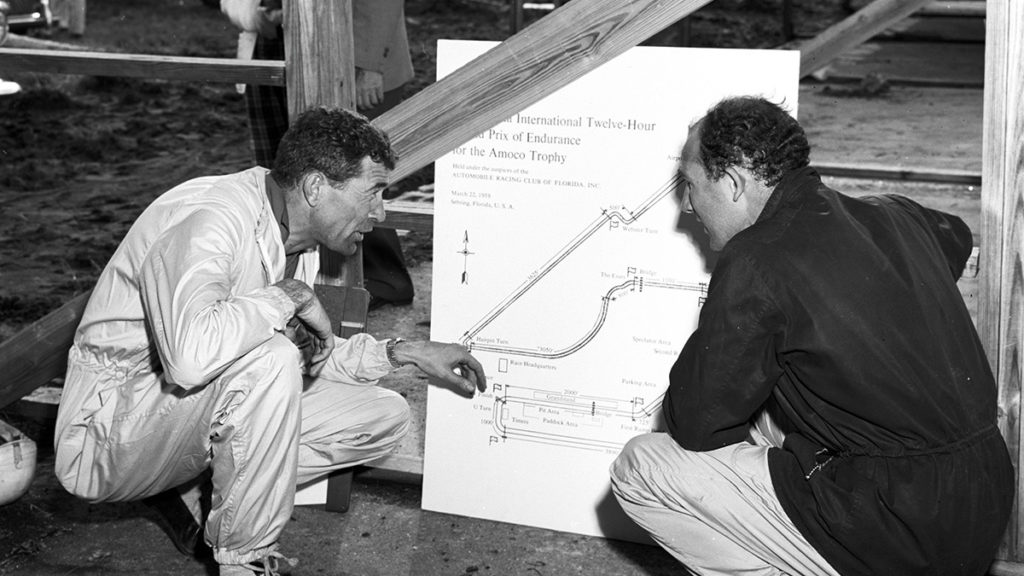

- Moss chats with Aston Martin stable-mate Carroll Shelby before the 1958 Sebring 12 Hours. Moss would share his DBR1/300 with Tony Brooks and ran well until gearbox failure put them out after 90 laps. Shelby and Roy Salvadori fared even worse, with their transmission letting go after just 62

- Moss in the pits during the British Grand Prix meeting at Silverstone, July 1958. Although he retired his Vanwall from the main event with engine failure, after qualifying on pole, Moss took a works Lister-Jaguar to victory in the supporting International Daily Express Sports Car Race. Back then, it was all in a day’s work…

- Moss takes a swig after finishing second in the non-championship Supercortemaggiore race at Monza in 1956. He shared the factory-run Maserati 200S with Cesare Perdisa

- At the wheel of Rob Walker’s Ferrari 250 GT SWB, Moss heads Innes Ireland’s Aston Martin DB4 GT during the 1960 RAC Tourist Trophy at Goodwood, when he eventually built such a lead that he was able to switch on the car radio and listen to the race commentary! Moss scored seven RAC TT victories, three at Dundrod and four on the trot at Goodwood between 1958 and 1961

- Sweet in Sweden: Moss celebrates after winning the 1959 Kanonloppet (‘The Cannon Race’) at Karlskoga. Although the field comprised mostly local drivers, Moss faced some tough opposition – not least from that season’s world champion Jack Brabham, in a similar Cooper Monaco T49