Chapter 6: life after racing - Stirling Moss' journey to reshape his life

His career came to an abrupt halt against an earth bank at Goodwood, but the public never forgot Stirling Moss. In a candid discussion with Simon Taylor, he explained how he had reshaped his life after his accident

On the afternoon of April 23, 1962, the professional motor racing career of Stirling Moss ended against an earth bank on the approach to St Mary’s Corner at Goodwood. The cause of the crash has been endlessly debated, but Stirling himself has no memory of it. “I remember chatting up a South African girl at a party the night before, and I remember knocking off the exhaust of my Lotus Elite that morning reversing out of the car park of The Fleece, John Brierley’s pub in Chichester. After that, nothing. I woke up six weeks later in a room filled with flowers, and I remember thinking vaguely, ‘Somebody must have thought I was going to die.’”

The race was the Easter Monday Glover Trophy: a comparatively minor event, no championship points at stake, not even much glory. Stirling’s car was a Lotus-Climax, an elderly 18 chassis despite its 21 bodywork, owned by Rob Walker but running in the pale green colours of the British Racing Partnership. It was well out of the running, having already been delayed by a pitstop to fix a jamming gear selector on the Colotti gearbox. Graham Hill’s BRM was comfortably in the lead, and the Lotus was two laps behind.

But Stirling always regarded whatever race he was doing today as the race that mattered. It was typical of the man that he wanted to give the paying spectator value for money, and there was still the outright lap record to go for. He’d already equalled the new record, set a few laps earlier by John Surtees’ Lola, and there was more to come.

I was in the St Mary’s grandstand that day, a teenage Moss fan revelling in my hero’s progress. I watched him climb back to seventh place, driving very hard as he always did, smooth, stylish, head back in the cockpit, arms outstretched. With seven laps to go he came up behind Hill’s BRM to unlap himself. As Hill moved left to take his line for the beginning of the right-hander, the Lotus ran onto the left-hand verge at around 115mph, and straight into the bank.

Why? Theories have included some sort of mechanical failure – jammed throttle, braking or steering malfunction – or that Hill acknowledged the marshal’s blue flag with his left hand, and Stirling misinterpreted that as a signal to pass Hill on the left. As far as could be established from the wreckage, the brakes were functioning and the car was in fourth gear, which would have been Stirling’s usual ratio at that point. We will never know the truth, although Stirling says now, “My mother told me Graham went up to her later and said, ‘I didn’t mean that to happen.’ I think he probably did move across on me, quite frankly, not realising I was already there.”

Moss at Goodwood in May 1963, driving one of BRP’s Lotus 19s during a private test session. Although his lap times were reasonable, he decided there and then that his professional career had run its course as the driving process no longer came to him as naturally as it had before his accident one year earlier

The impact against the bank was immense and, in the manner of spaceframe cars of the early 1960s, the Lotus folded up like a penknife. Hearing that he was trapped in the wreckage, BRP’s Tony Robinson and Stan Collier leapt into the team’s Morris Minor van, drove onto the circuit – while the race was still going on! – and rushed to the scene. It took marshals and helpers 45 minutes to cut the unconscious Moss from the car, Tony and Stan carefully removing the battery and lifting off the fuel tank over his legs. Mercifully there was no fire. He was taken to Chichester Hospital and then to the Atkinson Morley Hospital in Wimbledon.

His head injuries – no seatbelts, of course, and a thin Herbert Johnson crash helmet – were dreadful: the left side of his brain was massively bruised and partly detached from his skull, and his left eye socket was crushed. His other injuries included a broken leg and broken arm. He did not properly regain consciousness for 38 days. When he did come round, he was partially paralysed, and he could not speak.

In 2009 it is difficult to comprehend – even though F1 racing was very much a minority interest then, with none of the TV and media coverage of today – how huge a presence Stirling Moss was in the national consciousness. He was one of Britain’s most famous men, and the whole country was galvanised by his accident and hungry for news of his condition. Unlike today, with 24-hour news channels and hourly bulletins on every radio station, back then the BBC Home Service only broadcast the news four times a day. The only exceptions were emergency announcements in time of war, or when the King was dying. Yet I clearly remember, as one of millions horrified by the injuries suffered by the world’s greatest racing driver, that Stirling was treated like royalty. In the days immediately after the accident, when most expected him to die, the BBC ran hourly radio bulletins on his condition.

As he regained full consciousness his will to recover, which had worked miracles after his 1960 Spa accident, began to assert itself. “When I started to come round I knew I’d had an accident, but I didn’t know where or when. Then I realised the left side of me was paralysed, so I started to focus on the bits I couldn’t move. It gave me something to work on. Eventually I started to get a slight movement in one finger of my left hand, so I concentrated on that, then I moved on to the other fingers, and then the whole hand. Lying there, I assumed absolutely that I would get back to racing. I reckoned I’d had much worse accidents – breaking my back and my legs at Spa I came back pretty quickly after that. So I just thought, I’ve got to get on with this. But gradually it dawned on me that it was much more serious than I’d realised.”

On July 20, nearly 13 weeks after the accident, he left the Atkinson Morley, greeted by a huge press posse outside the hospital. Hobbling on crutches, he took the 11 nurses who had looked after him out to dinner, and gave each of them a small gift. “I went to Nassau to recuperate. But I was still in a bit of a state. I couldn’t remember anything, and my body temperature was different one side to the other. One cold hand, one hot hand. My speech was slurred, so people thought I was drunk. And I had no concentration. To open a door I had to think, consciously, ‘Put your hand on the knob. Now turn it.’ But the press gave me no peace. There were even paparazzi on the roof of the hotel in Nassau, with long lenses. Everybody was asking, ‘When are you coming back? Are you going to race again?’ The papers kept running stories about it. There was a lot of pressure on me to make up my mind. I knew I had to get the decision out of the way.”

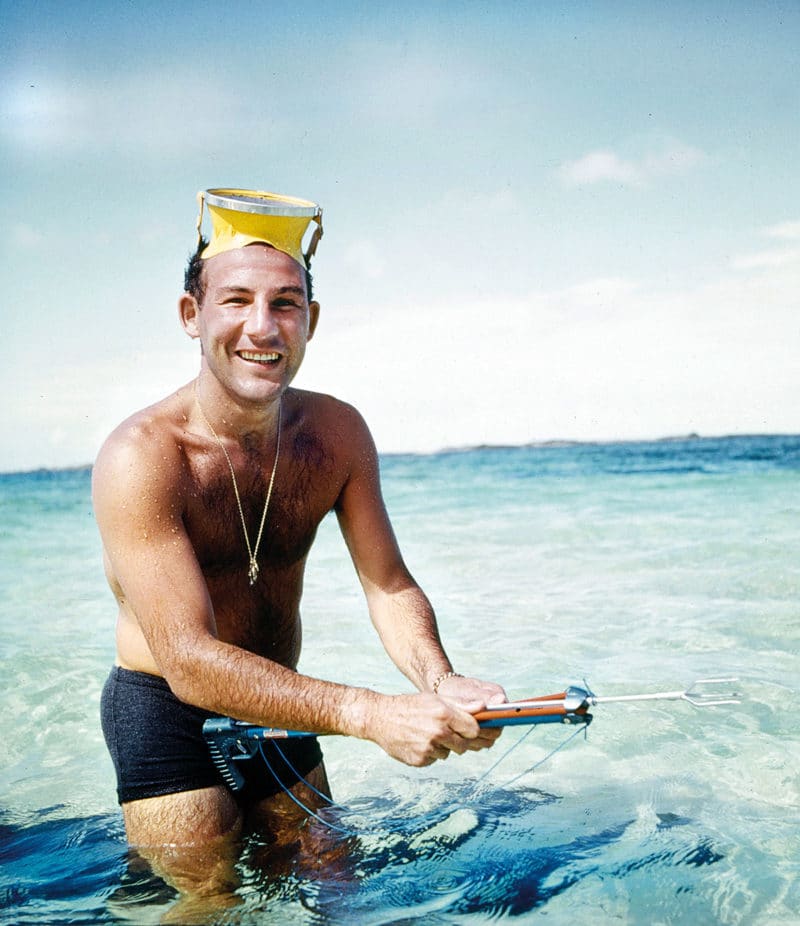

Moss had raced regularly in the Bahamas, during the traditional Nassau Speed Week, and in late 1962 he was back there again, this time to recuperate

So just over a year after the crash, on May 1, 1963, a damp grey day, Stirling drove a Lotus 19 sports car around an empty Goodwood. As he went through St Mary’s no memories of the accident came back. He drove at proper racing speeds – at one point he spun coming out of the chicane – and his times in the conditions were competitive. But as he got out of the car he knew his decision was made.

“My times were quite reasonable, I was on the pace. But I found that I had to do everything in the car consciously. I’d approach a corner and think, ‘I’ve got to get over to the edge of the road here, I’d better brake now, this is where I should get back on the power.’ It all had to be worked out, nothing was automatic any more. Before, I could always jump in a car on any circuit, and get straight down to within a fraction of my best time. Then, if I wanted to put in a quick one, if I was going for pole, I’d work at coming off the brakes a little earlier, getting back on the power a little earlier. But I couldn’t do that in the same way, it was all a conscious effort. I no longer had the capability I’d had before. That was it. It was a depressing decision to have to take, but it was a very easy decision, because it was obvious to me that I wasn’t what I had been. If I couldn’t come back at the top, there was no point. I didn’t want to come back as second-best, my pride wouldn’t let me. That same evening, back in London, I announced my retirement.

“In the years after that I sometimes wondered if I took the decision too early. If I’d waited two or three years I think my faculties would have come back, my concentration and my focus. By then Jim Clark had established himself as the best, and he might have been really tough to beat. When I raced against him he hadn’t reached his maturity: when I beat him, he was no faster than Innes [Ireland], but he got much faster than Innes later. But once I’d said I was out, I was out. If people retire, and then change their minds and come back, well, I don’t like that sort of thing.

“For years I’d been well paid by the standards of the day. Because I was busy racing every weekend, I didn’t go out and spend money much, apart from chasing crumpet. But I hadn’t salted much away. In my last full year, 1961, I grossed £32,700. Out of that I paid all my own expenses, hotels, flights – I always flew economy – and after expenses I paid tax on £8000. I suppose that was roughly what a good lawyer would have earned in those days. But you paid very high tax rates then, so I probably netted about £3200.

“Before the accident I had every intention of going on until I was 50. After all, Fangio won the world championship when he was 46. At 32, I was at the top of my game. I didn’t see why I couldn’t do another 15 years or so. I was as versatile as I’d ever been, and I was enjoying racing in all types of car. Nowadays drivers get out earlier because they make so much money, and 32 is old. But even if I’d been making the money they make today, I’d have stayed racing. I wasn’t doing it for the money, you see. I just loved the racing. The fact I didn’t make a lot of money was just part of how life was then.

“After I announced my retirement, I woke up next morning with no idea what I was going to do. I tell you, boy, suddenly finding you have to earn a living when you’ve been paid to have fun all the time, that was a bitter pill to swallow.

Moss receives a helping hand as he leaves the Atkinson Morley Convalescent Hospital, Wimbledon, in June 1962

“I had no qualifications to do anything. As a teenager, before I started racing seriously, I’d done a couple of things in the hotel trade – night porter, working in the kitchens – but if you know nothing about anything, there are only two jobs available to you: estate agent or Member of Parliament. I didn’t want to be either of those. The Sunday Times was sponsoring a Cobra at Le Mans, and they asked me to be team manager, so I did that, but it was a publicity thing really. I’d never make a real team manager. I would demand too much. I’ve always demanded a lot from myself, but I know what I can do. I couldn’t start demanding it from somebody else. So I began to dabble in property. My father, who had about 16 dentistry practices around the London area, was starting to retire, and I took over his premises, rented the surgeries to other dentists, and got tenants for the properties upstairs. I began to understand how all that worked, and I bought a few small properties.

“I had an insurance policy which was meant to pay out £30,000 if I couldn’t earn my living as a racing driver. The premiums had been costing me a couple of grand a year. After the accident the insurance company tried to wriggle out of it. They said, ‘You’re walking around, you’re doing things, you can live a normal life.’ I told them I’d insured as a racing driver, and now I couldn’t race any more. I was going to have to take them to court, but at the last minute they paid up.”

Although it hadn’t been announced at the time of his accident, Stirling was going to be a Ferrari driver in 1962. While remaining loyal to Rob Walker, for whom he’d raced for three seasons in Formula 1, he had negotiated an extraordinary agreement with Enzo Ferrari under which he would race a dark blue Ferrari with a white noseband. “Rob was going to run it, but Ferrari agreed to support it and give us all the latest bits. And there would be a Dino 246 for sports car racing and a GTO for GT events. Because Rob only wanted to do F1, those two were going to be light green, in the colours of the British Racing Partnership, which was set up by my father and Ken Gregory, with Tony Robinson running the cars. We were going to go public with it as soon as the F1 car was delivered – which was meant to be in time for Goodwood. But the factory was running behind schedule. If I’d had the car for Easter, I suppose I wouldn’t have had the accident. So the late delivery of that car changed my life.”

(In fact a Ferrari did turn up three weeks later, for the Silverstone International Trophy. It was a 1961 car, painted red, but with a tartan sticker across the nose denoting BRP’s sponsors, UDT. Innes Ireland drove it into a lapped fourth place, and then the car was returned to Italy. The pale green GTO was delivered, however, and Ireland used it to win the TT at Goodwood that year.)

Meanwhile, even though Stirling’s place on the race track was taken by other British heroes – Jim Clark, Jackie Stewart, later Nigel Mansell and Damon Hill – the public refused to forget him. He remained in the public eye, and was called on more and more to make speeches and public appearances, open garages and supermarkets, and pronounce on any matters of public interest and concern that had a motoring slant.

The remarkable thing is that Stirling Moss was a professional racing driver for barely a dozen years, and a long time ago. Yet today, 47 years after that Goodwood crash took him out of the sport, he is still a universally popular figure, and his name has remained a household word. Always a patriot – he is one man who would never live abroad for tax reasons – he received a knighthood in 2000. Now Sir Stirling and his beloved wife Susie, who organises his life so efficiently, are busier than ever. From their base in Shepherd Street, Mayfair, where he has lived for more than 40 years in a house he designed himself, they travel all over the world. So what is the secret of his enduring appeal?

“I suppose it’s because I’ve always tried to make myself approachable. I’ve been listed in the phone book all my life. I’m a nosy bugger, always like to keep tabs on what’s going on, and if the media call up wanting to know what I think of the new Minister of Transport, or the latest FIA row, I’ll always have something to say. My diary is completely full now, which is how I like it because I’m happiest when I’m on the move. I love to keep doing things – as you know, my motto is ‘Motion is Tranquillity’. Susie and I are a team. We work seven days a week, we fit into each other’s pockets. She remembers everything and everybody: I call her my filing cabinet. We travel hundreds of thousands of miles a year, a lot of it to historic car events – the Mille Miglia in Japan, the Mil Millas in Argentina, judging the concours at Pebble Beach, demonstrating at the Goodwood Festival of Speed – and always at these things there are nice people. It takes me back, and I enjoy it. I have a good relationship with Mercedes-Benz, who seem to like reminding people about the 1955 Mille Miglia. Other companies that I drove for, too: I did a dinner at Le Mans for Aston Martin customers. And I do talks to businessmen, motor clubs, organisations all over the world.

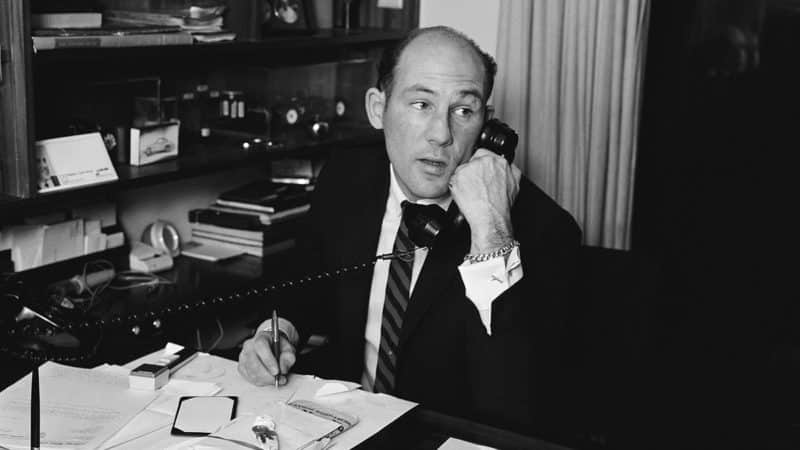

This was taken in February 1966 and photo agency Getty’s caption describes him as “British Formula 1 racing driver Stirling Moss”… No matter what else he did, or how long he had been out of the cockpit, his association with the sport he’d graced became indelible

“One reason I’m so busy is that the modern F1 drivers are impossibly expensive. If Kimi Räikkönen is earning £30 million a year, how much are you going to have to pay him to set aside a day to open a shopping mall? Or Lewis or Jenson, or any of today’s names? Fortunately for me people still remember my name, and I’m more affordable. I call myself the international prostitute. You get me there and pay me, and I’ll do the job.”

But a significant amount of Stirling’s travel is because, after all, he is still racing. He first got back into a race car in 1978, when he and Jack Brabham did the Bathurst touring car race in Australia, in a Holden. “I told Jack to start, because I thought Jack always used to get away well, and he got hit up the arse on the grid. Then I did a celebrity race at Macau, in a Cortina or something, and Mike Hailwood took me out. But my injuries had all long since healed, and it felt pretty good.”

That led, in 1980, to a drive with Audi in the British Touring Car Championship. “Worst decision I ever made in my life. I signed for two years, and it’s something I never should have done. It was a new type of driving, which I wasn’t equipped for. They all drove into each other. If my car wasn’t bent at the end of the race I wasn’t going quickly enough. I was astounded by the lack of ethics among the drivers. Some of them were quick, but none of them had any ethics. And I’d never raced on slicks before. Slicks meant I had to do things that I didn’t find easy – I learned to brake at half the distance, but I didn’t enjoy it. I am a treaded-tyre person.

“But then historic racing was coming in, and as soon as I got into historics I was home. The downside is that I used to be paid to race, and now I’m driving my own car it’s costing me a fortune. But I love it. I’ve had a C-type Jaguar, an Elva-BMW, a Chevron, and I’ve driven cars for other people, 250F Masers and D-types and so on. Now I’ve got this beautiful little 1500cc Osca, the only one with desmodromic valve-gear. This season we’re having a lot of fun – Le Mans Legends, then Oporto, Donington, Goodwood, Spa. I’ve noticed that corners which maybe would have been flat when I was younger, like say Eau Rouge at Spa, I’ll try to kid you I’m flat, but probably I’m not, not quite. If I ever felt I was getting in other people’s way, then I’d stop. My ego wouldn’t allow me to race against similar cars to mine if they were way ahead of me.

“It’s important to me to be able to race in my old helmet and overalls, and after a lot of effort I got special dispensation for that from the FIA. I signed a waiver saying if I get hurt because I’m wearing incorrect clothing, no belts, no rollbar, it’s my fault. It’s important to me: the pleasure I get is partly because I’m in the car just as things were, the way they should be for a car of this period. I’m not against other people wearing modern protective stuff, but there aren’t many people around now who know what it was like then, and I think it’s good for them to see the driver as well as the car looking correctly in period. If you look at a picture of me racing the Osca, you can’t tell if it’s 2009 or 1959.

“Many more people are interested in the history of racing now, too. Amazingly I still get three or four fan letters every day, most from the UK and Germany, some from America. Anybody who sends me a letter gets an answer. I’ve always done that, even at the height of my career. I think it’s important.”

This energetic, entertaining and courteous man is still jetting around the world, still racing and racing well in historic events, still a personality respected and welcomed everywhere, giving pleasure to thousands. It’s almost half a century now since the dreadful accident which nearly killed him, an accident that would have stopped most ordinary human beings in their tracks. But this is an extraordinary human being. Long may he continue to be the youngest, fastest-moving, retired racing driver around.

- BRDC patch still prominent in 1977

- Moss tries the dodgems at Battersea Fun Fair in 1968

- When he joined fellow racers John Surtees and Denny Hulme in Nice Time, a Granada TV series; he spent two seasons – 1980 and ’81 – in the British Saloon Car Championship with Audi, but didn’t enjoy it

- Filming a then-and-now feature with Lewis Hamilton at Silverstone, 2013

- Stirling and wife Susie at the Ennstal Classic, Austria, in July 2015

- As well as retaining strong links with Mercedes, Moss has done likewise with Aston Martin and is seen here in a DB3S at Goodwood, 2016

- CHICHESTER, ENGLAND – SEPTEMBER 09: <> at Goodwood on September 9, 2016 in Chichester, England. (Photo by Michael Cole/Corbis via Getty Images)CHICHESTER, ENGLAND – SEPTEMBER 09: Sir Stirling Moss in Aston Martin DB3S, owned by Steve Boultbee Brooks, in the Assembly Area at Goodwood on September 9, 2016 in Chichester, England. (Photo by Michael Cole/Corbis via Getty Images)

- Sir Stirling and Lady Moss taking part in a stage of the 2008 La Festa Mille Miglia rally in Miyagi, Japan