Stirling Moss at 1957 Pescara road race - a battle between driver, terrain and rivals

In 1957, Pescara hosted an old-fashioned road race that formed part of the Formula 1 World Championship and, as our correspondent Denis Jenkinson reported, it was as much a battle between driver and terrain as driver against driver. It was a conflict Moss was well equipped to fight

The town of Pescara, on the Adriatic coast of Italy, is famous for many things. It is a holiday resort for the Italians, it is the point on the Mille Miglia route where the race turns inland over the Abruzzi mountains, it is the last outpost of civilisation when venturing down into Calabria by road, it is invariably very hot, but above all it has a wonderful motor racing history.

The 25-kilometre circuit, one of the longest used for grand prix racing, lies on the edge of the town and goes up into the mountains, through the villages of Montani and Spoltore and down again through Cappelle, to join a long, fast straight that runs at right-angles to the Adriatic until it meets the Via Adriatica at the village of Montesilvano, and then it runs south down the coast road back to Pescara.

The entire circuit is comprised of normal, everyday Italian roads, it runs slap through the centre of villages, and contains every known hazard of normal motoring, such as kerbstones, bridges, hairpins, rough surfaces and every type of bend and corner imaginable. Out in the country section, the road is bordered by fields, trees, high banks, hedges, sheer drops and solid concrete walls; in fact, the whole thing is pure unadulterated road racing.

It is the sort of road racing that is traditionally Italian, and the circuit is one of those like the Nürburgring, the Targa Florio, Naples or Dundrod, where the battle is not between driver and driver, nor even between car and car, but the battle between the combination of car and driver against natural surroundings. After driving around the Pescara circuit, the fact that one driver beats all the others and wins a race seems subsidiary to the principle task, which is to cover 18 laps of this fantastic old-time, real, road-racing circuit.

The history of the Pescara track goes back many years, as far as 1924 when a certain Enzo Ferrari was the winner, driving an Alfa Romeo. Since then its grand prix has been connected with such names as Varzi, Nuvolari, Fagioli, Rosemeyer, Caracciola and Trossi in pre-war days. Here the fabulous Mercedes-Benz versus Auto Union battles were waged, poor Guy Moll lost his life driving for the Scuderia Ferrari, Whitney Straight began a series of wins for British cars in the Voiturette race that preceded the grand prix for the Coppa Acerbo, his win with an MG being followed by victories by Hamilton with an MG and Seaman with an ERA.

Pescara was always a great name in road-racing circles and after the war it was soon back on the scene, but money was not so plentiful in that part of Italy and the race diminished in stature. Even so, the names of Ascari, Fangio and González, along with Maserati, Alfa Romeo and Ferrari, carried on the traditions of this great circuit. When times became a bit harder, sports cars took over the scene and Bracco, Marzotto and Hawthorn added their names to the list.

The winner had enough of a lead to be able to make a precautionary stop late in the race. It was a chance to top up the Vanwall with oil and its driver with water

It seemed that Pescara and its wonderful circuit were going to drop out of the grand prix scene, for the trend was towards artificial road circuits like Reims, Spa, Aintree and Silverstone, but at long last the Pescara Grand Prix has been able to reinstate itself as a major event, and to count for the Grand Prix World Championship. The mountains and villages of the Abruzzi once more have been ringing to the sound of the best grand prix engines of today, and just as Nuvolari and Rosemeyer pitted all their skill and the power of their cars against the local conditions, so Fangio and Moss have done the same, those conditions changing hardly at all.

In view of the road being required for the normal everyday business of living, practice was confined to the Saturday before the race, the first session being at 7am and the second at 4.30pm and everyone was out in the early morning sunshine. The Scuderia Maserati entered a full team of four cars, with Fangio, Behra and Schell on 1957 lightweight six-cylinder cars, and Scarlatti with the old hack six-cylinder from last year, while in addition the latest V12 car was brought along. This was the offset-transmission chassis that first appeared at Reims and it was hoped that it would really sing along the straights with its 310bhp.

The main opposition came from the Vanwall team, with four cars, driven by Moss, Brooks and Lewis-Evans and the fourth car as spare. After looking at the line of blood-red Maseratis, it was a fine sight to see the four sleek and efficient Vanwalls, immaculate as ever, ready to pit science against brute force and experience. The Scuderia Ferrari was in a difficult position for Enzo was having a touchy dispute with the Italian government and the Automobile Club of Italy, so had refused to enter any cars at all, but at the last moment a single 1957 ‘Syracuse’ Lancia/Ferrari was brought along for Musso to drive.

In addition to these entries there were Halford, Gould, Godia and Piotti with their private Maseratis, and the Scuderia Centro-Sud with its two Maseratis driven by Gregory and Bonnier. The BRM team should have been there but decided against it at the last moment, and the total of 16 cars was made up by two Formula 2 Coopers from the factory, driven by Salvadori and Brabham.

Due to small modifications made to the circuit over the long period of years there has not been a consistency over fastest lap times, for when the pre-war German cars appeared on the scene in 1934 they were getting so far away from the Italians on sheer maximum speed that various chicanes were built into the long straights over subsequent years, and since the Second World War fast laps had been made during practice but not during the races.

QUALIFYING

Apart from all this, practice started with the knowledge that laps around 10min 15sec would be considered good for this 25-kilometre circuit. As has become a habit, Fangio set the ball rolling with 10min 14.9sec and Moss followed with 10min 20sec and then Behra stopped in a puff of white smoke indicative of a hole in a piston. Musso was soon charging round, clocking 10min 18sec and the battle was on. Having broken his six-cylinder car Behra took over the 12-cylinder, while Moss tried another Vanwall as his was not terribly happy on suspension. The surface of the Pescara circuit does not allow for suspension errors, and shock-absorbers and chassis were taking an awful beating. Since the Nürburgring, Vanwall had done some interesting sums over the matter of spring rates and damping, and it was showing signs of paying off on this hard circuit. Having settled in to the track, and the general atmosphere having stabilised, Fangio suddenly did a lap in 10min 04.4sec on his six-cylinder car, and at that the fun started. Musso got down to 10min 09sec and then did 10min 04.8sec, fractions of seconds difference in 25km of dicing. Then Moss went out and did 10min 05.8sec, so the heat was now really turned on. Fangio tried the V12 but found it about as hopeless as Behra had, and could not better 10min 20sec, while Musso was doing an enormous number of laps, trying all he knew to save the honour of Italy. He reduced his time to 10min 03.5sec amidst the cheers of the populace, and Brooks did a lap in 10min 08.8sec, which gave good support to Moss with the leading Vanwall.

The timekeepers’ line on this circuit is situated in the middle of the row of pits, and the procedure was to wheel the car back beyond the timing line and take a flying run at it when setting off on a standing lap, otherwise it meant the first lap would not be timed when starting off from the upper pits. Equally, the cars in the lower pits had to cross the timing line at the end of the lap, in order to record a time, and then stop very hurriedly and reverse back to the pits, or else go all the way round again. The resultant pandemonium in the pit area was wonderful to behold, with cars going in all directions, but it was all quite safe as everyone was on their toes to the situation.

After Musso’s fast lap Maserati warmed up Fangio’s six-cylinder car, but before he could take off Moss went away in the Vanwall, so the world champion allowed a little gap and then set off after him. While they were away on their 25-kilometre dice, activity in the pits was varied; some of the private owners were realising what a long way around it was for each lap and how hard it was on the car, especially without works backing, Ferrari was fairly happy with its one car, and Brooks and Lewis-Evans were conscious of the handicap of not having been to the circuit before.

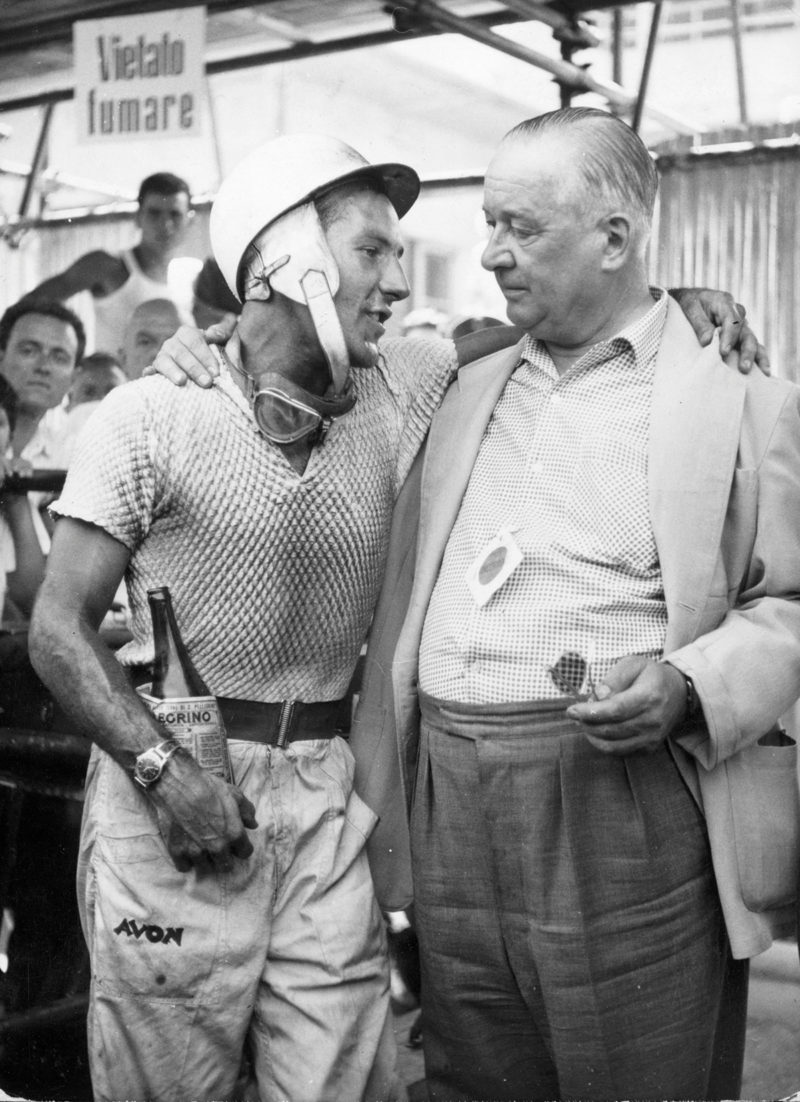

Moss with Vanwall patriarch Tony Vandervell. The British team was gaining real momentum in the slipstream of a breakthrough win at Aintree

Moss arrived back at the pits and a short time afterwards Fangio returned, but they did not stop and went on for another lap, neither of their opening laps being very spectacular. The next time they arrived a cheer went up from the happy crowds when it was announced that Moss had broken 10 minutes with a time of 9min 54.7sec, a really stupendous effort, but after Fangio had crossed the line, the loud-speakers bubbled over with excitement and the crowd screamed with excitement, as only an Italian crowd can perform. Fangio had done 9min 47.7sec, a speed of 156.486kph, and that just about finished the first practice period.

In the afternoon a surprising number of people were out, in fact only two of the private owners failed to turn up, and everyone went thrashing round the circuit again. The Vanwalls were going steadily, giving the appearance of not liking to go beyond a reasonable limit, and one felt that if the drivers tried to slide them into corners they would lose them altogether. The uneven surface of the road was playing havoc with the Vanwalls, setting up high-frequency wheel patter on the front, while the Maseratis were obviously suffering from shock loads being transmitted right through the car and giving the drivers a pretty hard ride.

It had not been very difficult to see that Fangio had been having a bit of a go, and his final lap time of 9min 44.6sec set the seal on his morning’s efforts. Moss did not improve on his morning time, but nearly equalled it, and Musso did 10 minutes flat, while Behra got down to 10min 03.1sec and Schell did a creditable 10min 04.6sec.

RACE

In view of the terrific heat of the midday sun, the start was planned for the delightfully vague time of “about 9.30am”, so that the 18 laps could be finished by the time the day was at its hottest, and from the early hours the populace streamed away into the mountains to sit on hillsides and banks and watch grand prix cars indulge in some real road racing. The actual start was a little chaotic to say the least, and one mechanic got scooped up on the bonnet of Gould’s Maserati as the 16 cars streamed away down the straight towards the winding section of the triangular circuit.

It was Musso in the lone Lancia/Ferrari who led the way round on the opening lap, though Moss was not far behind, followed by Fangio, Brooks, Behra, Gregory and Lewis-Evans. Musso, Moss and Fangio went through the start, but Brooks drew into the pits, the Vanwall showing signs of overheating and having internal engine trouble, possibly a burnt piston, so it was withdrawn before an expensive explosion took place.

As the tail-enders arrived at the corners before the pits, Gould went straight on into the straw bales and Piotti did not even appear on the horizon, engine trouble having intervened. Gould eventually reached the pits and retired, so the field was reduced to 13 at the end of only one lap. Up through the twists and turns Musso was keeping ahead of Moss, but only just, and before the lap was completed the Vanwall went by into the lead, and so hard were these two driving that Fangio and the rest were getting left behind.

Moss was really sliding the Vanwall through the corners, in a way that had not seemed possible in practice, and looking down into the cockpit from a high bank it could be seen just how hard he was working away on the steering wheel. The two Coopers were having a friendly scrap together, and actually leading Halford’s Maserati, while the bodywork on Gregory’s car was already beginning to shake loose. On lap three Moss was still leading, but Musso was trying really hard and hanging on closely, both cars using all the road and kicking up dust and stones from the corners. The Maseratis were not showing the turn of speed they had in practice, possibly because they were using a less potent fuel for the race, though various sources denied this, but whatever the cause Fangio and Behra were losing ground on the leading Vanwall and the lone Ferrari.

As Lewis-Evans went down the straight after the pits to start his third lap a tyre tread threw off, and he had to go the rest of the lap with a flailing rear tyre, so that he dropped back the whole time, and was relegated to the back of the field by the time he got to the pits for a replacement.

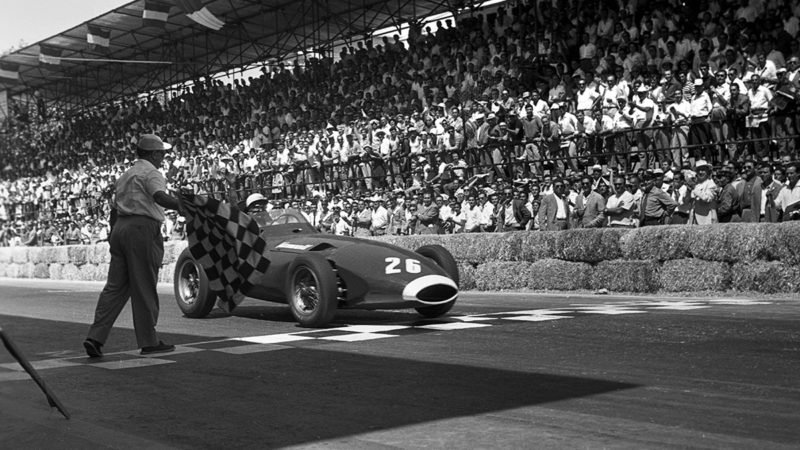

The end of a gruelling day for Moss. He might have been outpaced by Fangio during practice, but in the race the Englishman was in a league of his own once he had passed early leader Luigi Musso. It was the fifth of his 16 world championship grand prix successes and he smashed all existing circuit records en route to victory

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

On lap four Moss began to draw away from Musso by a second or two, while the gap between them and the Maseratis continued to widen and Behra had oil appearing all over the tail of the car. This was every bit as ominous as it seemed and he retired at the end of the lap with a very sick motor car, having had an unhappy time ever since he arrived at Pescara. Brabham called into the pits briefly, to report that Salvadori had overdone things and gone off the road, bending a rear wishbone but without personal damage, and this allowed Halford to get ahead.

On the next lap, with Behra out, Schell moved up into fourth place, but he had Gregory worrying at his tail and driving hard to keep up. In the other Centro-Sud Maserati Bonnier had the centre part of the bodywork come adrift and went around in a flurry of flapping aluminium, stopping at the pits to have it all screwed back together. Poor Lewis-Evans was right out of luck, for the other rear tyre began to throw bits of tread, and he had to stop once more for another new tyre, which kept him right at the back of the field.

Moss was now really into his stride and gaining seconds over Musso every lap, but the Ferrari driver was fighting as hard as he could and not giving up, and the Vanwall was proving too fast for anyone to catch it. Fangio was running a lonely third, but losing ground all the time, and Schell and Gregory were still in close company but a long way back. Then came Scarlatti all on his own, and Godia, Halford and Brabham; Lewis-Evans and Bonnier had been lapped by the leaders due to pit stops.

The lap times of Moss were being reduced with every lap, and he eventually covered his ninth lap in the all-time record time of 9min 44.6sec, but even so Musso was only losing 2sec a lap on him though Fangio was now more than a minute behind the leader. On the way up into the mountains for the tenth time, the oil tank on the Lancia/Ferrari split and – unbeknown to Musso – left a trail of oil on the road until the engine seized and his gallant drive came to an end. This left Moss way out on his own, and what really settled the matter was when Fangio slid on the spilt oil, bounced off some kerb-stones and buckled his left-rear wheel, having to slow down considerably while he carried on around the circuit with a very wobbly wheel.

At the pits he had a new one fitted, and the offside front tyre was also checked, that too having received a clout, and he rejoined the race nearly 3min behind Moss and with no hope of ever seeing the Vanwall again. Brabham stopped for fuel, and Bonnier stopped for good, the Maserati running a temperature and the bodywork coming adrift again. Moss was now out on his own, having vanquished all the opposition. The Vanwall hummed its way on through the mountains and down the straights.

Gregory was having a bad time with a scuttle that looked as though it was going to fall off, and he let Schell draw ahead to a comfortable third place, while Scarlatti in fifth was not too happy with a Maserati that was getting tired. Godia went out during the 11th lap with engine trouble and Halford did not start his 11th lap as some teeth came off the main driving gear in the transmission. Lewis-Evans was going all right now, but so far back he could not hope to catch up with anyone, and there were only seven cars left running. Before starting his 13th lap Moss stopped at the pits to take on oil, as the pressure was varying under braking, but with a commanding 3.5min lead he could well afford this. In spite of slowing his lap times to 9min 53sec Moss was still pulling away from Fangio, and Maserati was in a state of despair at such a thorough dusting-up by the dreaded ‘Wan-whol’ that had started not so long ago appearing to be just another British sporting attempt at grand prix racing, but which was now capable of beating the world in general and Maserati and Ferrari in particular.

Lewis-Evans was still not out of the mire, for he began to suffer from a sticking throttle, many times shot into corners much faster than he intended and taken all round was not enjoying his grand prix. Scarlatti stopped at the pits with a sick motor and no clutch, and after a lot of pandemonium was got going again. Seeing this the Vanwall pit signalled to Lewis-Evans and he began to press on, trying to catch the sick Maserati and take fifth place. Moss toured around for the last two laps, in complete command, and came home winner at record speed, holder of the lap record and having proved that the Aintree win was no fluke after all.

Along the 15 miles of normal two-lane country roads, Moss had, towards the end of the race, needed to steer around goats which had strayed into the road. This was a contest that would never be allowable in mainland Britain

This had been a hard, grim battle of man and machine against the local conditions, and though his team-mates all had trouble Moss had achieved a resounding victory in the finest type of grand prix road race imaginable. Fangio arrived in second place more than 3min behind, having for once been unable to overcome the handicap of being up against a superior machine, driven by a not-so-inferior driver.

It had been a tough grand prix in the real old traditional road-racing style – with an estimated crowd of 200,000 lining the track – and every driver who finished had needed to work really hard, while the machines had taken a greater battering than we have seen at this level for a long time. Lewis-Evans had pressed on to good effect and caught Scarlatti, taking fifth place behind Schell and Gregory, the young American driver having driven a good hard race.