Chapter 5: Stirling Moss' road racing prowess - a test of skill and courage

On lethal routes over hundreds of miles, road racing was the era’s ultimate test of skill and courage. It is no coincidence that it was on these dusty tracks that the Moss legend was truly forged

Motor racing is dangerous still. But it used to be dangerous in the extreme, when its cars and equipment paid little heed to safety, and the majority of its circuits were comprised of public roads, with all the natural and man-made hazards that entailed. Fatal accidents were common yet fell within bounds deemed acceptable by a public emerging from global conflict. It was the price paid for freedom.

And it was central to the thrill that Moss felt. As those less talented hesitated between the claustrophobic earth banks of Ulster’s Dundrod, or peered aghast over the vertiginous drops of Sicily’s Targa Florio, or stared incredulously down the long and narrow and cambered straights of Pescara – scene of a world championship grand prix, for heaven’s sake – he pressed home his superiority. Relentlessly. He did not lack for imagination – although it took some badgering/blackmailing by his father for him to don a ‘sissy’ crash helmet (of layered linen strips soaked in resin and lined with cork) – and certainly he suffered the pain of broken bones that went with the pleasure. But this was where, when and how ‘The Boy’ separated himself most obviously from the men.

And that was before it rained – surefooted Moss is a strong contender for being the all time greatest in the wet – and before mention is made of the Mille Miglia. His 1955 victory in this 1000-mile tear-up of Italy is perhaps the most famous in all of racing. Guided by Motor Sport’s stoic continental correspondent Denis Jenkinson and his ‘bog roll’ of route/pace notes, Moss averaged 99mph for more than 10 hours. He brushed a hay bale or three, launched over a fifth-gear brow of underestimated severity, and escaped from a ditch on the Radicofani Pass, but pressed on unabatedly – as brilliant 25-year-olds tend to – because at no stage did he feel sure of victory. He won by more than 30 minutes. Runner-up Fangio was delayed by fuel injection bothers, but it had been highly unlikely that he was going to beat his younger (by almost 18 years) team-mate that day; he knew it, even if Moss didn’t. The Argentinian, a hardened veteran of his continent’s crazy cross-country enduros, was beginning to parcel out his performances: he did not enjoy the Mille Miglia; he had not prepared as thoroughly as had Moss; and he was, if necessary, willing to concede to the fit-as-a-flea Englishman in two-seaters as long as their status in Formula 1 remained unchanged.

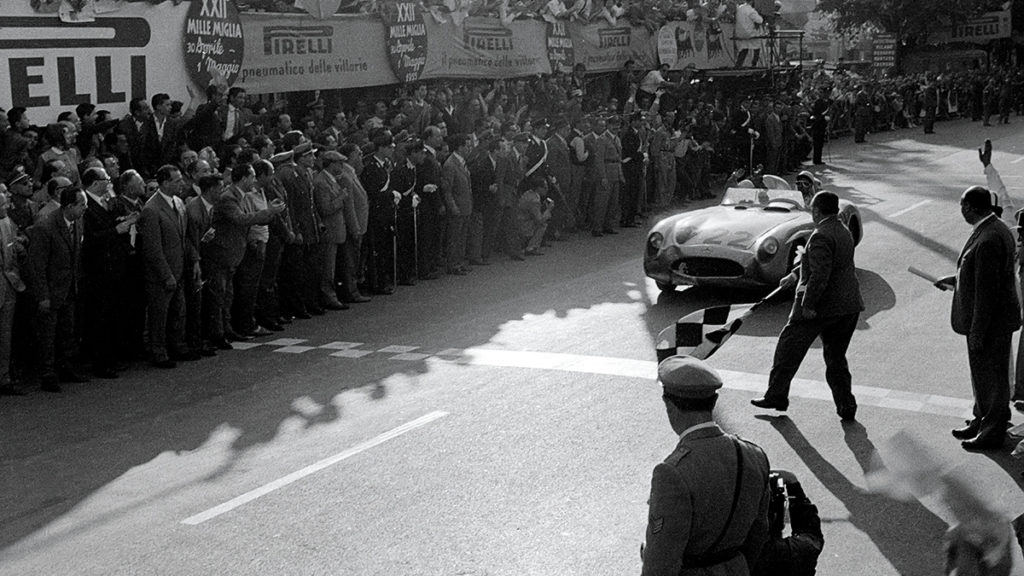

The grit and grime underline that Moss had put in quite a shift over the previous 10 hours, but he still managed to conjure a fresh-looking smile at the conclusion of the 1955 Mille Miglia, one of his – and motor racing’s – greatest performances

This keynote season would feature Moss also winning the RAC Tourist Trophy at Dundrod – after a high-speed blow-out had ripped off the right-rear bodywork – and the Targa Florio – after plunging over a drop that he had never paused to peer over: the 300SLR was teak-tough and he took full advantage of that. Mercedes in turn benefited to the tune of a world title.

Moss just had the long-distance knack: the balance, the concentration, the stamina. Even so, it took him days to recover from his victorious effort for Aston Martin against Ferrari in the 1958 Nürburgring 1000Kms. He left nothing on the table. When first he climbed aboard a hairy-chested sportscar after three seasons spent mainly tackling sprint races and short hillclimbs aboard spindly single-seaters, he did so at the kindly but knowing behest of a family friend, after Britain’s myriad manufacturers had politely but firmly turned him down: Boy Dies in Man’s Car was a headline that they could do without, thanks. The first day of practice for the 1950 RAC TT, a three-hour race at Dundrod, was indeed an eye-opener for Moss: Tommy Wisdom’s Jaguar XK120 was not only powerful but also relatively heavy and somewhat disinclined to stop. Come race day, however, he would be leading by the second lap and was never headed thereafter, winning on the road as well as on handicap, his driving as calm as the weather was wild. That evening, a few hours before his 21st birthday, he was invited to join the works Jaguar squad for 1951.

Thus it was a sportscar in a road race that kicked-started his professional journey, and though Moss could and would drive (pretty much) anything, (pretty much) anywhere, this combination remained a powerful motif throughout and beyond his career. For these are the victories – those achieved on truly hazardous circuits, in cars plainly unsafe by today’s much narrower bounds – that continue to mark him out as unbelievably special, were they not true.

- All roads lead to Rome… and back. After 10h 07min 48sec, Moss and Motor Sport’s Denis Jenkinson return to Brescia to complete the 1955 Mille Miglia. Uncertain that his victory was secure, Moss never once let up; he finished more than half an hour clear of team-mate Juan Manuel Fangio. One of Moss’ finest moments also inspired one of the greatest pieces of sporting reportage, hand-written subsequently by ‘Jenks’

- Colour photography has been around since the late 19th century, but was still quite rare at motor racing events in the 1950s. Paris-born Yves Debraine captured a relaxed Moss at the wheel of a slightly battle-worn 300 SLR on the Mille Miglia’s Futa Pass

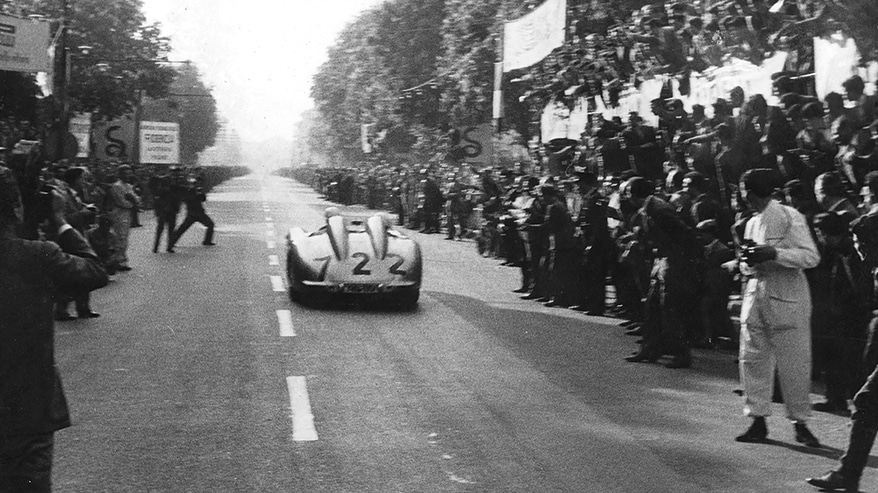

- Just another 10h 07min 46sec to go. As Jenks’ note on the print mentions, right from the start they were swiftly travelling at speeds that would nowadays be thought wholly incompatible with the surroundings

- A stain-scarred Moss takes in his latest RAC TT victory, at Dundrod in 1955, as co-driver John Fitch looks on. Despite losing time when a tyre failed and damaged their Mercedes 300 SLR’s bodywork, the Anglo-American duo recovered to win by more than a lap from team-mates Juan Manuel Fangio/Karl Kling and Wolfgang von Trips/André Simon

- Moss in the pits at Dundrod, where he recorded three of his RAC TT victories. The first of those, in 1950, came at the wheel of a Jaguar XK120… and victory led to the offer of a works contract with the Coventry firm the following season. He returned 12 months later to win the race again, beating team-mate and fellow C-type driver Peter Walker. This is from 1955

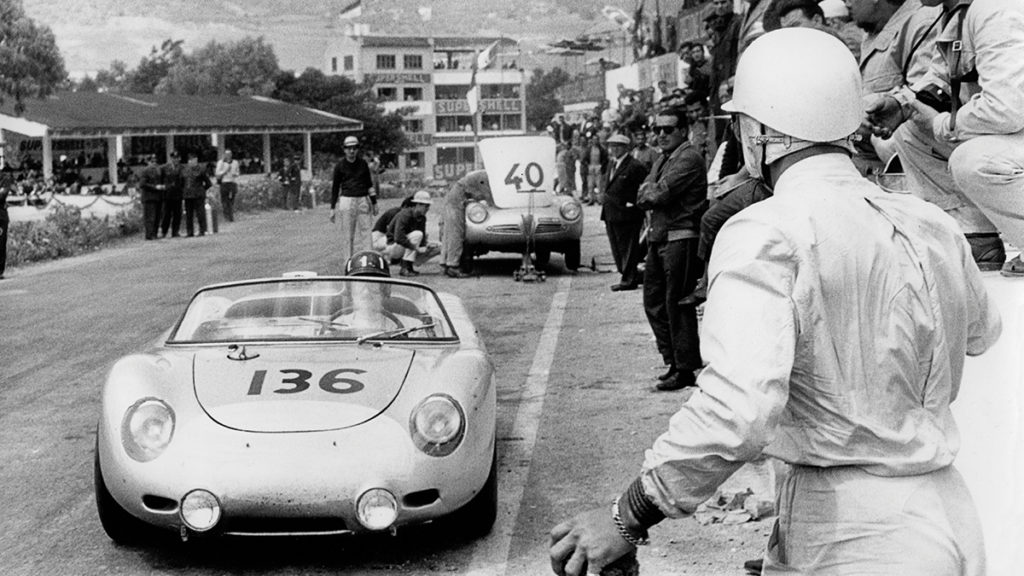

- Moss’ Porsche RS61 on the 1961 Targa Florio. Describing the 72km lap, Motor Sport’s Denis Jenkinson wrote: “Some of the corners had been lined with steel barriers, so instead of going straight over and down the mountainside, anyone out of control would now bounce back and go over the edge a bit further on, a mangled wreck before leaving the road…”

- Moss waits to take over from Graham Hill on the 1961 Targa. He had built up an early lead, lost to Ferrari while Hill (who had little Targa experience) was at the helm, but moved ahead once again and looked set to win… until his Porsche’s crown-wheel and pinion failed with just seven of the 720km still to run

- Despite his many road-racing successes, things did not always go perfectly to plan for Moss. One year on from his spectacular Mille Miglia success, he and Jenkinson salute the crowd ahead of the 1956 race. Unfortunately they would slither off the road in slippery conditions. Unhurt, the pair later made their way back to Brescia by train instead

- Moss and Jenks hurtling towards victory on the 1955 Mille Miglia. According to DSJ (Motor Sport, June 1955), “This win was not a fluke, it was the result of weeks, even months, of preparation and planning. When I met Moss early in the year to discuss the event, it transpired that he had very similar plans, of using the passenger as a second brain to look after navigation”

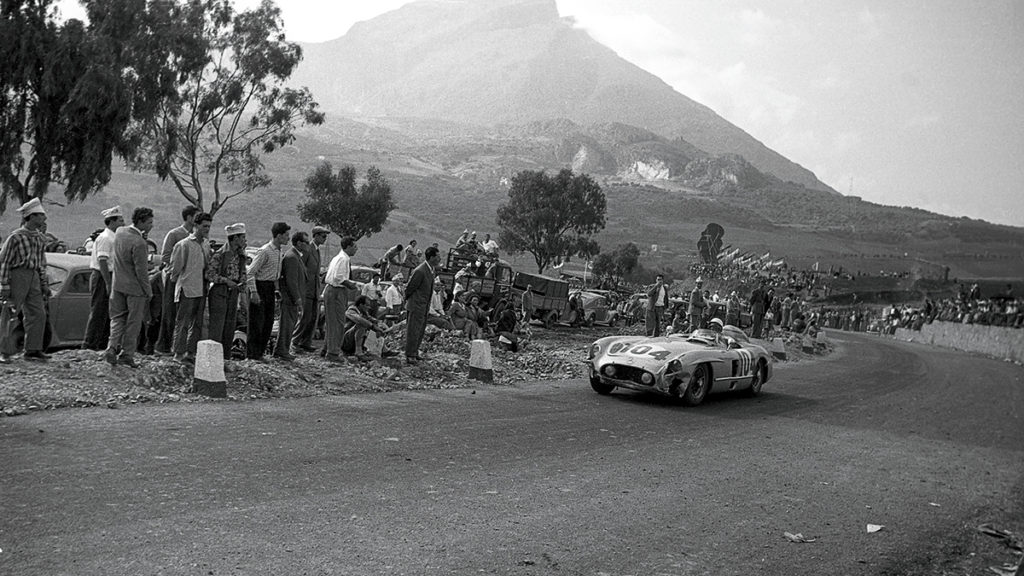

- The 1955 Targa Florio was the first to count towards the World Sportscar Championship and three manufacturers – Mercedes, Ferrari and Jaguar – were in contention following the penultimate race of the season, the RAC Tourist Trophy in Dundrod. The British team did not enter the Targa, however, leaving a straight fight between Stuttgart and Maranello. Ferrari had a three-point advantage going into the race, but Moss and Peter Collins headed a Mercedes 1-2-4, ahead of Juan Manuel Fangio/Karl Kling and Desmond Titterington/John Fitch – enough for their team to take the title by two points

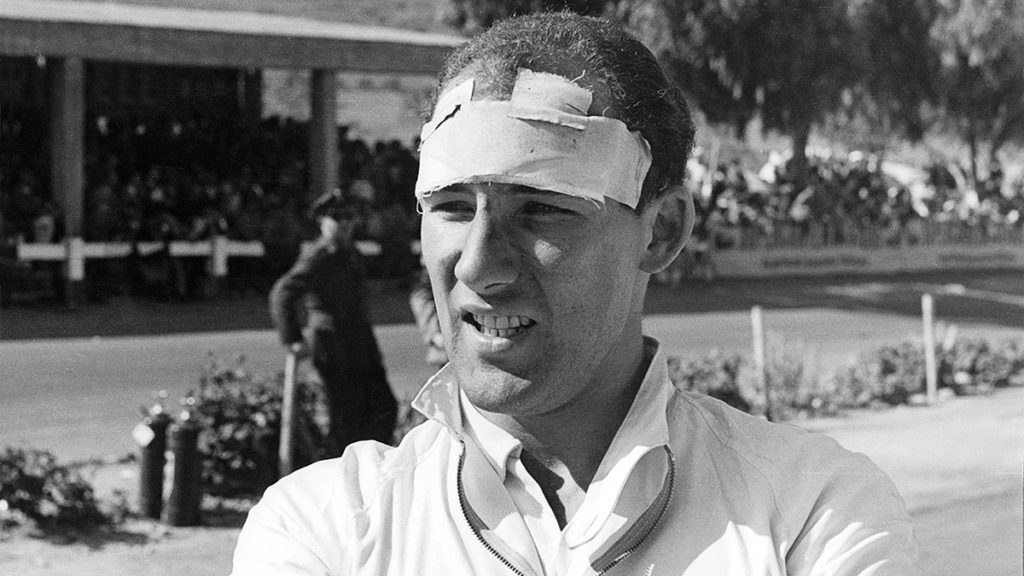

- There were some very obvious potential perils bordering the route of any race that took place on public roads, but more prosaic injuries were also an occupational hazard. A patched-up Moss awaits his next turn at the wheel during the 1955 Targa, some facial bruising having been inflicted by rocks thrown up from the less than billiard-smooth road surface. Such details didn’t impede progress; he and Peter Collins finished the best part of five minutes clear of the rest

- The frayed state of the 300 SLR underlines that progress on the 1955 Targa wasn’t always as smooth as Moss often made it look with his laidback posture at the wheel. First run in 1906, the event was a round of the World Sportscar Championship from 1955-1973 and carried on until 1977 as a national event before growing safety concerns led to its abolition. As the photographs on this and preceding pages illustrate, concepts such as run-off areas and supervised spectator zones were completely alien… yet this was the environment in which Moss conjured some of his most memorable victories

- Things racing drivers tend not to do in the modern age… For all that he was freakishly fit and able to drive incredibly long stints when required, Moss wasn’t averse to the occasional cigarette – and even cashed in on his celebrity to advertise Craven A. “I don’t smoke often, but when I do I’m choosy…” He and Peter Collins share a smile, a handshake and a smoke in the slipstream of their success on the 1955 Targa Florio