1967 Le Mans 24 Hours: The greatest race of them all?

My lamented friend Jabby Crombac always considered the 1967 Le Mans 24 Hours to have been the greatest in the long history of the race. The quality of the entry,…

In 1895, the Lumiére brothers presented projected moving pictures to a paying audience for the first time. In 1896, commercial production of automobiles began in the United States. It didn’t take long before someone had the bright idea to put a car in a film. Movies and motors have been teaming up ever since. They’ve practically grown up together.

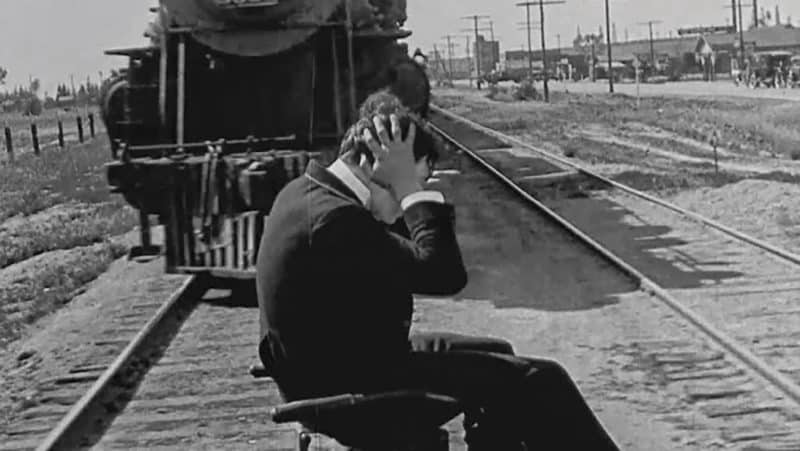

Like any long-term relationship, both parties have evolved, becoming technologically more complex and ambitious over time. We’ve gone from Model Ts to Teslas and from Kinetographs to GoPros. When Buster Keaton was almost hit by a train in a chase scene from 1924’s Sherlock Jr minds were blown by the simple use of back projection. By the 1960s, the camera was actually in the car. Today, the Fast and the Furious franchise is built on trying to deliver something that might not have been possible even one film before. The consistent advances in technology – in both the motor and the movie business – are part of the reason the partnership endures. It’s a symbiotic relationship.

Racing movies also reflect the times. From the silent wonder of the 1920s when both cars and cinema were still brand new, to the more pulpy racing flicks of the ’30s and ’40s, full of drama and danger as cinema started to define its genres. The ’50s brought the beginning of more mature, ambitious stories while racing movies in the ’60s often reflected a jet-set glamour that most of the public only knew from what they saw in glossy magazines. With the ’70s came the counter culture and a questioning of everything before the glossy hyperbole of the ’80s (just compare and contrast the ambitions of, say, Le Mans and Days of Thunder…). As we reached the end of the century, documentary techniques – and documentaries – would become prevalent, and the past became a regular source for stories. Sometimes utilising old footage (Senna) sometimes making glossy reimaginings (Rush). But the lure of capturing speed on film continues to inspire each generation of film-makers.

As Ford v Ferrari (Le Mans 66) producer Peter Chernin said: “A great racing movie can provide us with all of the reasons we want to sit in a movie theatre. High stakes, life or death, big action, huge emotions. We want to be invested. We want to be moved, to cry to laugh… to be inspired.”

Buster Keaton in Sherlock Jr (1924)

Sherlock Jr

The inspiration started with just the visuals. Speed came before sound. Even when movies were still silent, fast cars were already appearing on the big screen. You couldn’t hear the engines roar but you could still watch them flash by. Cinema’s first racing cars appeared in comedies.

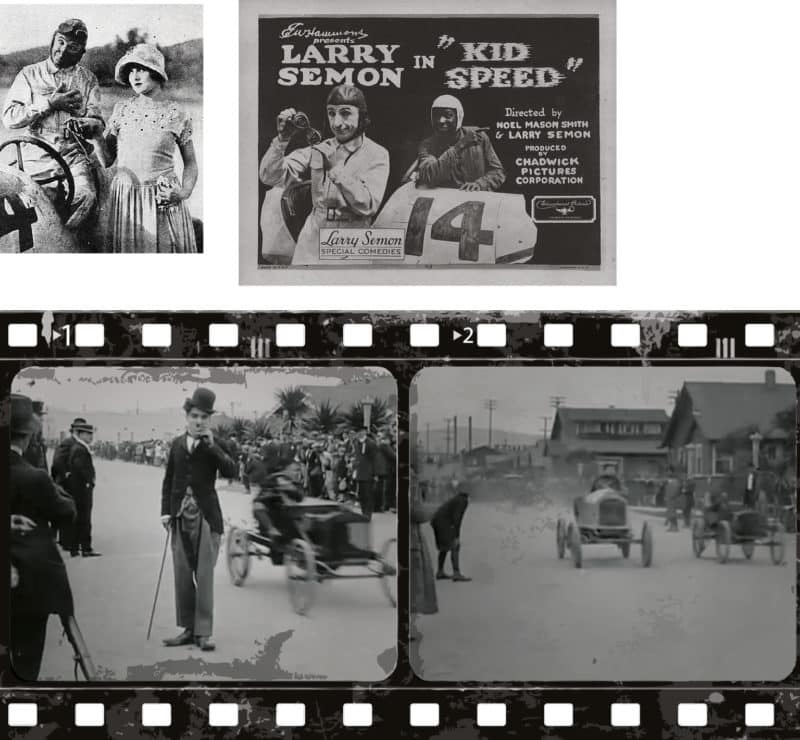

Fatty Arbuckle’s The Speed Kings grabbed pole position in 1913. The eight-minute silent comedy was set at a track and featured footage of actual races. Plus real life racer Teddy Tetzlaff and a throwaway plot about a girl (early silent star Mabel Normand) infatuated with him. More memorable was the following year’s Kid Auto Races at Venice, which starred Charlie Chaplin and offered audiences their first look at his ‘Little Tramp’ character.

The six-minute movie showed Chaplin as a spectator at a “baby-cart race” in Venice, Los Angeles. The film was shot during the actual Junior Vanderbilt Cup race, with Chaplin and co-star Henry Lehrman improvising gags in front of real-life spectators. A review at the time declared it “The funniest film we have ever seen. Chaplin is a born screen comedian; he does things we have never seen done on the screen before.”

Kid Speed (1924), Kid Auto Races at Venice (1914), starring Charlie Chaplin

Kid Speed, Kid Auto Races at Venice

The first (slightly) more serious offering to feature racing was the action romance The Roaring Road about a car salesman called “Toodles” Walden who becomes a race car driver. The 1919 film proved successful enough to spawn a sequel in 1920 called Excuse My Dust, where Toodles’ wife wants him to give up racing. The two films confirmed to studios that the public liked to watch fast cars on screen and prompted numerous car-related releases for the rest of the decade. Mostly comedies because that was still the prevalent genre. Of note is 1924’s Kid Speed, because it features Oliver Hardy (before he teamed up with Stan Laurel) and 1929’s Speedway, a rare drama about a father and son who are both racing the Indy 500. Much of the film was shot at that year’s race, courtesy of 14 cameras including an on-track camera truck.

The Crowd Roars (1932)

The Crowd Roars

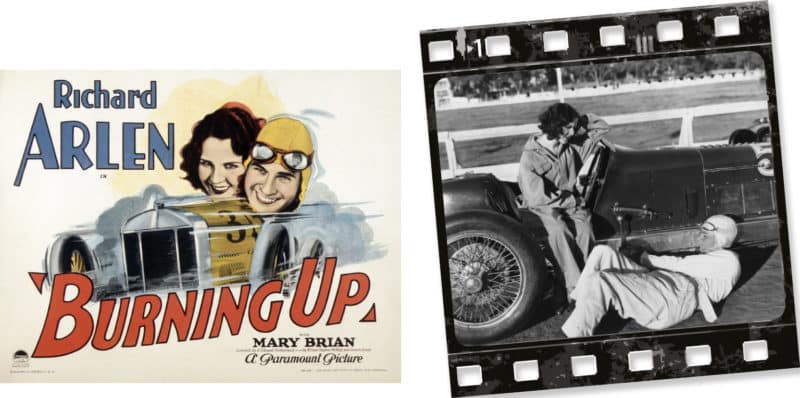

By the end of the 1920s, talkies were replacing silent movies and 1930 drama Burning Up was the first racing picture with sound. It starred Richard Arlen as a racing driver and Mary Brian as his love interest, the daughter of a fellow driver. It also had some motorcycle stunts but little else in the way of plot originality. As a review at the time observed: “It’s the old racing-car scenario brought up to date with sound and talk.”

1932’s The Crowd Roars was a little more notable. It was directed by Howard Hawks and has real star power with James Cagney and Joan Blondell. The somewhat overwrought plot (two racing driver brothers clash over women) was alleviated by some ‘flashy’ driving sequences featuring Indy 500 racer Harry Hartz. It was also the first film to use rear projection to simulate racing. The following year’s High Gear went one better by using car-mounted cameras.

Burning Up (1930) was the first racing movie with sound

Burning Up

In 1936 came Speed. It didn’t have a bus with a bomb but it did star James Stewart in his first leading role, as an auto mechanic and driver who develops a revolutionary new carburettor for racing. Although only a low budget B-movie, the film employed surprisingly realistic cinematography, smartly incorporating scenes from the Indy 500 and also shooting on location at the Muroc dry lake bed in the Mojave Desert, which was often used for high-speed hot rod racing at the time. The film also employed what would become a common publicity angle: it bragged about its leading man’s driving prowess – sharing with the world’s press that Stewart had driven at speeds in excess of 140mph during filming.

Poster for Blonde Comet (1941)

Blonde Comet

The 1940s introduced the first female driver on screen. 1941’s Blonde Comet starred former figure skater Virginia Vale as a female racing driver who competes around Europe before returning to the States and finding romance with a fellow driver. (“She raced men…And then she fell for one!”)

Blonde Comet aside, movie racing mostly took a back seat during the war but returned in 1949 when Mickey Rooney (then the biggest box office star in the world) took the lead in The Big Wheel as a brash young driver out to win the Indy 500. (“Thrilling,” said the Los Angeles Times). The following year Clark Gable starred in To Please a Lady as a reckless racer who performs stunts to raise money to compete in the Indy 500. He doesn’t win but he does indeed please a lady – earning the love of Barbara Stanwyck. The film had a crew of 70 shoot the actual Indy 500 that year and when three-time winner Mauri Rose’s car caught fire in the pits they used footage of the incident in the film.

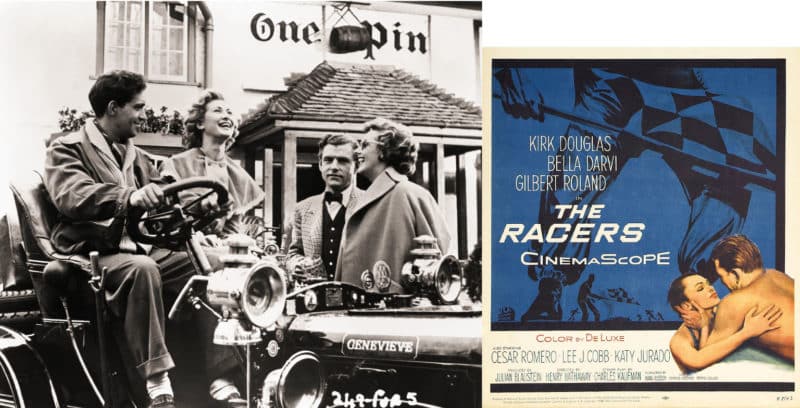

Genevieve (1953) was the year’s hit movie, while things got more ambitious with the release of The Racers, starring Kirk Douglas. While it lacked a decent script and had an array of comedy accents, it did boast some solid racing footage and great cars

Genevieve, The Racers

Britain finally offered an entry into the racing genre, kind of, with the charming if not particularly high-octane Genevieve. The 1953 comedy from The Rank Organization follows two couples competing in the annual London to Brighton Veteran Car Run. It was a huge hit, spawning numerous other comedies from Rank and seemed to be repeated on British television every Sunday afternoon for several decades.

1954 featured a now-familiar title when The Fast and the Furious hit screens. No Vin Diesel of course, this was more of a film noir as a truck driver called Frank unjustly imprisoned for murder, escapes and ‘borrows’ a Jaguar XK120 from a glamorous blonde who eventually forgives him for kidnapping her and stealing her car. Naturally, the pair fall in love and decide to compete in a cross-border sports car race so Frank can escape to Mexico. Shot in just 10 days, it was one of the first films from B-movie king Roger Corman. Coincidentally, the same year had Tony Curtis also compete in a stolen car in a race to Mexico. Johnny Dark was the first of three racing movies Curtis would make in his career.

The Fast and the Furious as you’ve likely never seen it before…

The Fast and the Furious

The most ambitious racing movie of the 1950s was probably 1955’s The Racers starring Kirk Douglas as an Italian bus driver obsessed with winning the Napoli Grand Prix with his homemade car. The script is… not great. The acting is worse and some of the ‘European’ accents are extraordinary. But the film does feature some glorious real racing footage from the era, an array of stunning grand prix cars and locations (including Monaco, Monza and the Nürburgring) plus some impressive stunt driving by American racers John Fitch and Phil Hill. The use of rear projection, which included overhead views, was also a significant step forward from previous racing films.

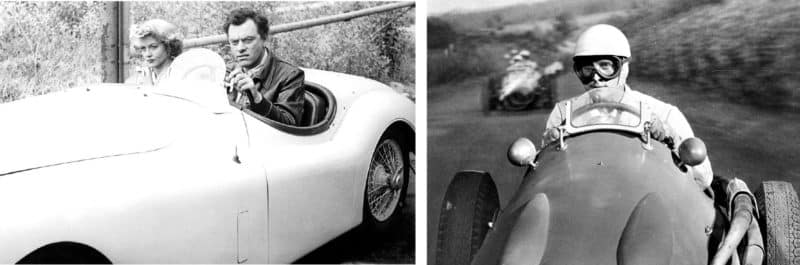

Grand Prix (1966); Fireball 500 (1966); Spinout (1966)

Grand Prix, Fireball 500, Spinout

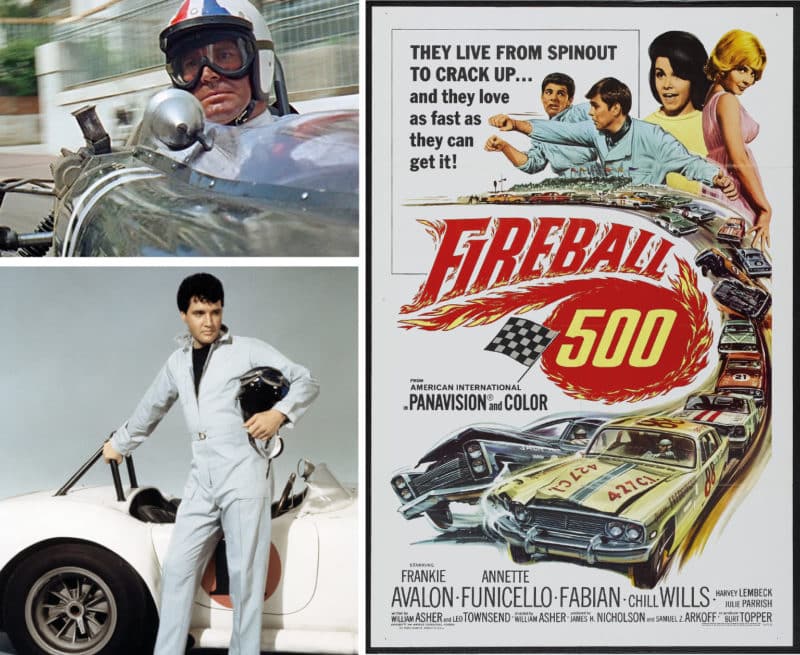

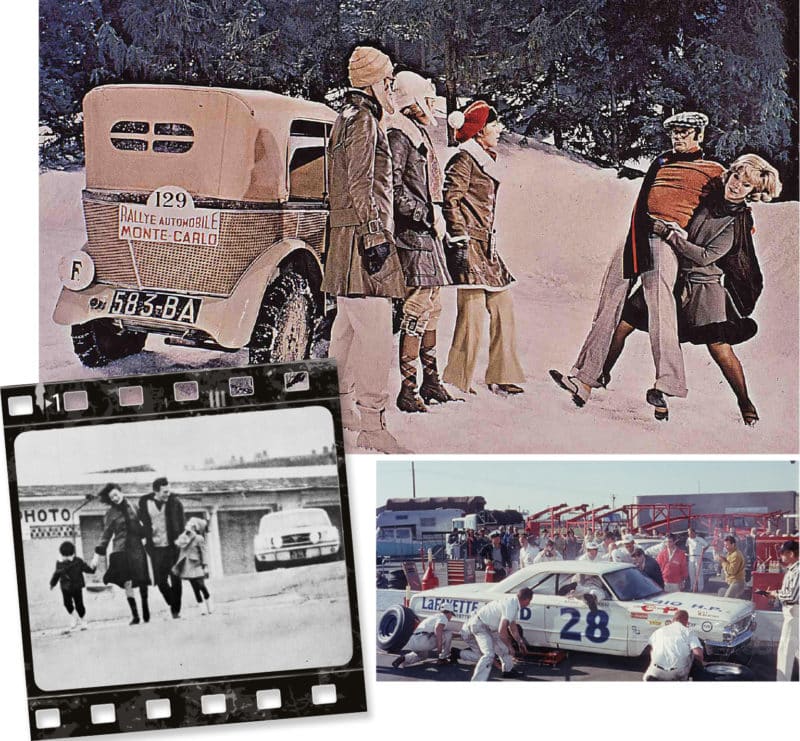

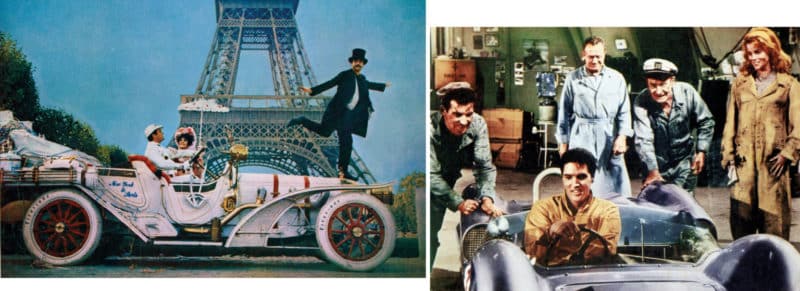

The 1960s brought a lot of bright, colourful and generally light-hearted motoring films including three with Elvis Presley behind the wheel (1964’s entertaining Viva Las Vegas, 1966’s harmless Spinout and 1968’s dated Speedway) and two period pieces with Tony Curtis. 1965’s The Great Race was a pretty good slapstick comedy based (very) loosely on the 1908 New York to Paris Race. Directed by Blake Edwards, it was nominated for five Academy Awards, boasted “the greatest pie fight ever” and also featured Jack Lemmon and Natalie Wood. 1969’s Monte Carlo or Bust (known in the US as Those Daring Young Men in Their Jaunty Jalopies) was not quite as sparkling but has its moments. Based on the Monte Carlo Rally and set in the 1920s, it was a co-production between the US, the UK, France and Italy with an enormous international cast that included Peter Cook, Dudley Moore and, um, Eric Sykes.

Aiming for a slightly more serious racing approach was Howard Hawks’ Red Line 7000, which was set in the world of stock car racing and featured a not-yet-famous James Caan. The 1965 film utilised lots of real-life racing footage, including spectacular crashes but was somewhat undone by its lack of star power and soapy, unfocused plot lines. It was soon forgotten about with the arrival of the most significant racing film of the 1960s: John Frankenheimer’s Grand Prix, which in 1966 redefined what was possible and remains the benchmark for ambitious racing movies to this day. The same could not be said about that year’s Fireball 500. A stock car racing movie mixed with the ‘beach party film’ genre of the day starring singing actors Frankie Avalon, Annette Funicello and Fabian, it was a tall tale of race drivers and moonshine runners that miraculously spawned a sequel Thunder Alley.

Red Line 7000 (1965); Un Homme et Une Femme (1966); Monte Carlo or Bust (1969)

Red Line 7000; Un Homme et Une Femme; Monte Carlo or Bust

By this point it felt like a racing movie was coming out almost every month. Between 1966 and 1969 there were 16 films released with motor racing themes. Apart from Grand Prix, the most notable two were probably Un Homme et Une Femme and The Love Bug.

The first, a 1966 French arthouse release about a love affair between a race car driver and a young widow, captured the imagination of a global audience, earned over $14m at the box office (the equivalent of around $125m today) and won two Academy Awards (Best Screenplay and Best Foreign Language Film), a BAFTA, two Golden Globes and the Palme d’Or at Cannes. Sequels followed in 1986 and 2019.

The Great Race (1965); Viva Las Vegas (1964)

The Great Race; Viva Las Vegas

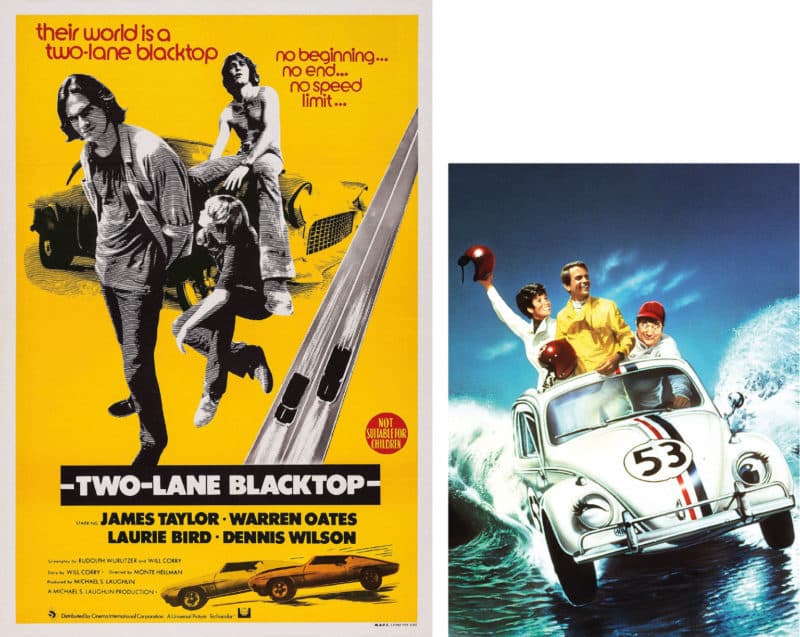

Two-Lane Blacktop (1971); Le Mans (1971)

Two-Lane Blacktop; Le Mans

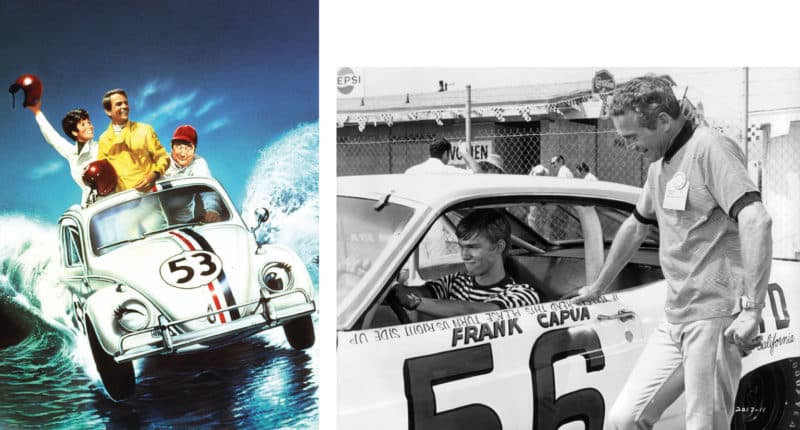

The Love Bug also captured the world’s imagination. The Disney film introduced audiences to Herbie, a Volkswagen Beetle so charming he’s practically the vehicular equivalent of Paddington Bear. Herbie competes in the Monterey Grand Prix and can drive himself, although he graciously allows his driver Jim Douglas to steer him on occasion. Volkswagen did not actually give permission to use its brand so officially there is no VW name, logo or shield in the film (although eagle-eyed viewers might spot the logo briefly during shots of the brake pedals and the ignition key). The film was a smash hit making back over 10 times its $5m budget. To date there have been four theatrical sequels and a TV series – for all of which, Volkswagen has happily allowed its brand to appear.

The end of the 1960s brought Paul Newman’s Winning. The start of the ’70s had Steve McQueen’s Le Mans. That would be the end of superstar-led racing movies, at least for a while. But the decade would provide some interesting fare (in between Herbie sequels). Such as existential road movie Two-Lane Blacktop, which starred singer/songwriter James Taylor and Beach Boy Dennis Wilson as street racers and featured almost as little dialogue as Le Mans. US newspaper Village Voice called it “achingly eloquent” while Esquire called it 1971’s “movie of the year”, which in hindsight feels a little generous.

The Love Bug (1968); Winning (1969)

The Love Bug; Winning (1969)

1972 brought Roman Polanski and Frank Simon’s documentary Weekend of a Champion which offered an insider view of Jackie Stewart at the Monaco Grand Prix – including a fascinating tour of the circuit narrated by the Scotsman.

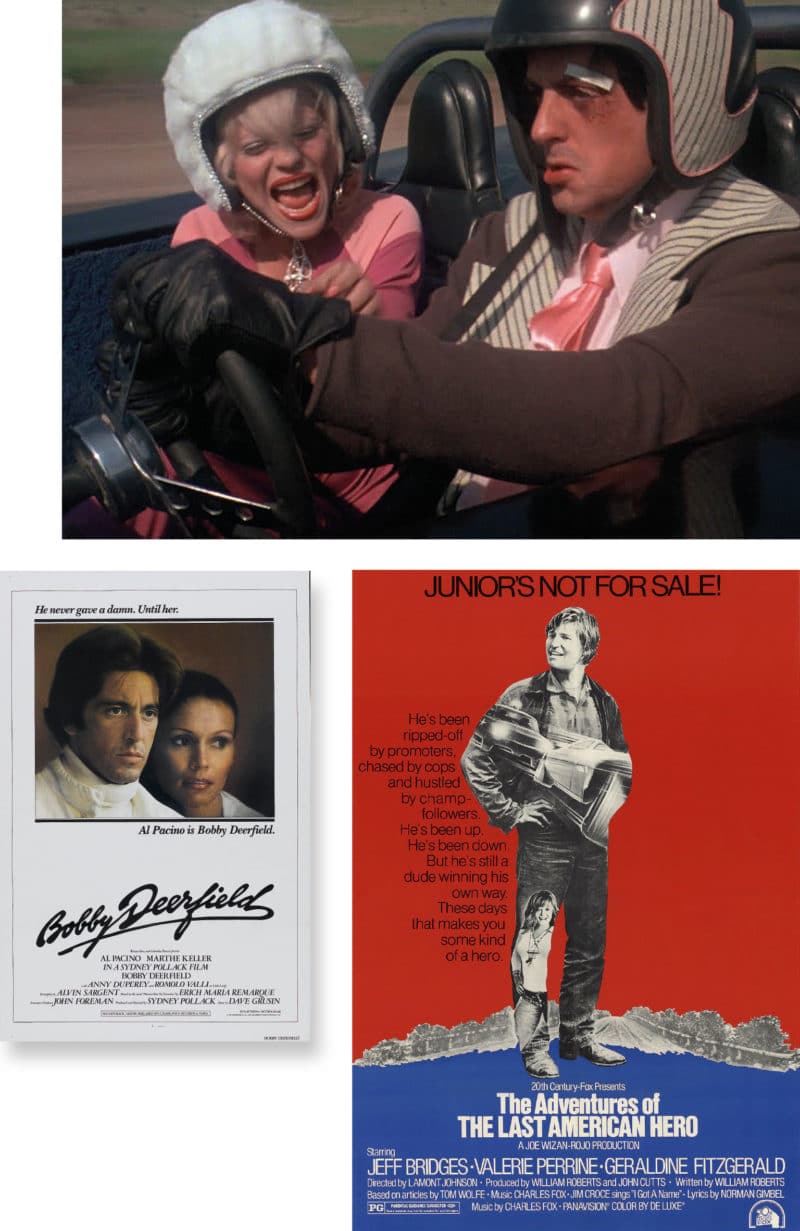

The film was re-released in 2013 in a new edit with an added 15-minute epilogue where Polanski and Stewart reminisce. Jeff Bridges played a NASCAR driver in 1973’s The Last American Hero, a small gem of a movie that has aged remarkably well. As has, in a different kind of way, 1975’s Death Race 2000, a science-fiction action film where a group of drivers race across the country in the murderous Transcontinental Road Race. What seemed vulgar and violent then now seems rather campy and fun.

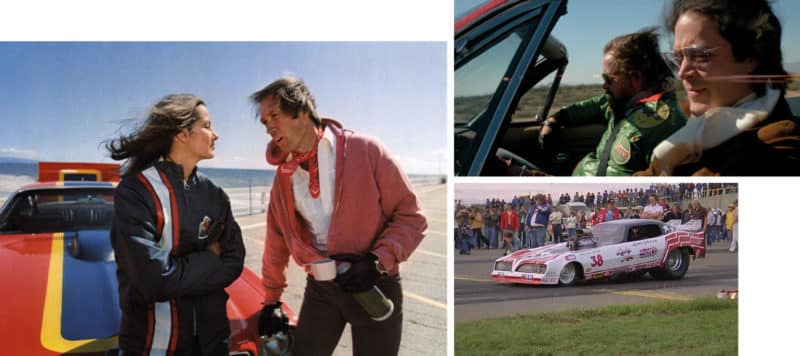

The Cannonball Baker Sea-To-Shining-Sea Memorial Trophy Dash, a somewhat ludicrous idea for a race event from Car and Driver writer Brock Yates, inspired two movies in 1976: the trashy exploitation flick Cannonball and the more comedic and likeable The Gumball Rally, which was directed by veteran stuntman Chuck Ball so at least had some good set pieces. (It also inspired the real life Gumball Rally and Gumball 3000 event.)

The Gumball Rally (1976); Fast Company (1979); Cannonball (1976)

The Gumball Rally; Fast Company; Canonball

The mawkish Bobby Deerfield in 1976 wasted the talents of Al Pacino as an American race driver competing in Europe who falls in love with Marthe Keller’s quirky Lillian, a Swiss woman who it transpires is terminally ill. The year also featured Richard Pryor playing Wendell Scott, the first Black NASCAR winner in Greased Lightning. Pryor is good (as is co-star Pam Grier) but the film is perhaps more admirable in its intentions than its execution. The last racing movie of any note in the seventies was Fast Company, a Canadian action film about drag racers directed by David Cronenberg. It bears almost none of the usual Cronenberg traits (no psychological stuff, no body horror, in fact no horror at all) but the director – an avid car enthusiast – remains fond of it.

Death Race 2000 (1975); The Last American Hero (1973); Bobby Deerfield (1976)

Death Race 2000; The Last American Hero; Bobby Deerfield

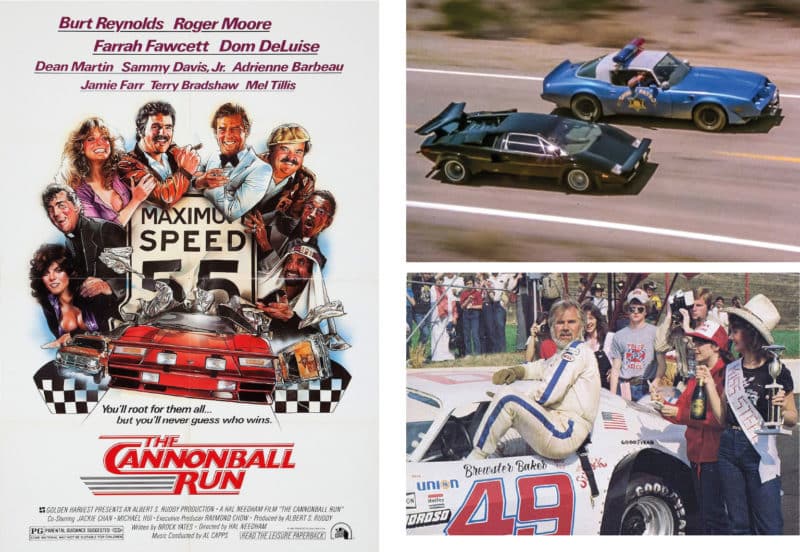

The Cannonball Run poster and action shot (1981); Six Pack (1982).

The Cannonball Run; Six Pack

By the start of the 1980s, Herbie was running out of steam. Fourth instalment Herbie Goes Bananas was the weakest entry in the series. However, a new franchise was around the corner.

1981’s The Cannonball Run was yet another film inspired by the Cannonball Baker event. This one was actually written by event creator Brock Yates based on his initial idea for “a race where competitors will drive any vehicle of their choosing, over any route, at any speed they judge practical, between the starting point and destination”. Hal Needham’s action comedy featured an all-star ensemble including Burt Reynolds, Dean Martin, Jackie Chan, Farrah Fawcett, Sammy Davis Jr, Dom DeLuise, Adrienne Barbeau and then James Bond, Roger Moore, as the improbably named Seymour Goldfarb who, for reasons never fully explained, identifies himself in the film as actor Roger Moore and signs into the race under that name. It was a smash hit, making $160m dollars back on its $16m budget. 1984’s Cannonball Run II was not as good while 1989’s Speed Zone (also known as Cannonball Fever and Cannonball Run III) was barely recognisable as the same series.

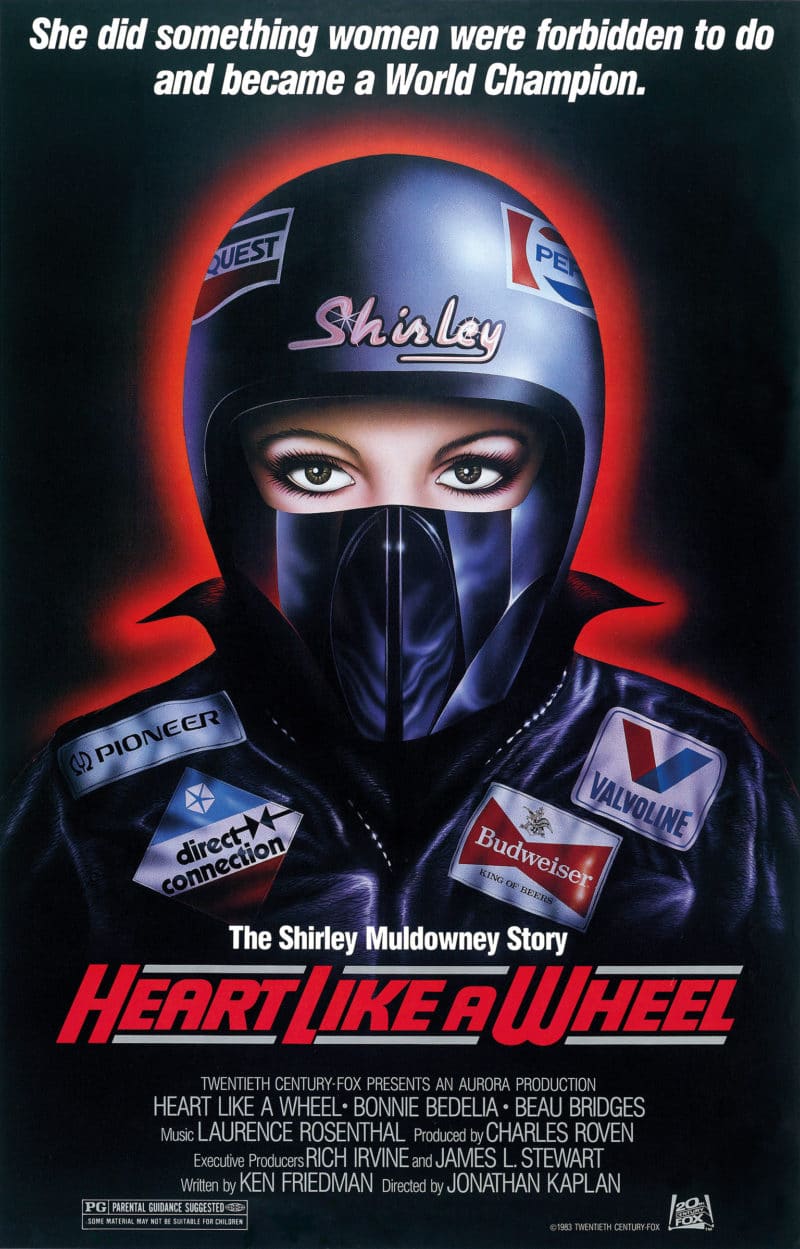

Heart Like A Wheel (1983)

Heart Like A Wheel

The decade offered few other racing films of note. Kenny Rogers starred in (and sung the theme tune) for the long-forgotten Six Pack a comedy-drama about a struggling NASCAR driver who teams up with six “car-crazy kids” and revives his career. Bonnie Bedelia played real-life drag racing driver Shirley Mulowney in the middling Heart Like a Wheel and Burt Reynolds and Hal Needham failed to replicate previous successes in NASCAR comedy Stroker Ace.

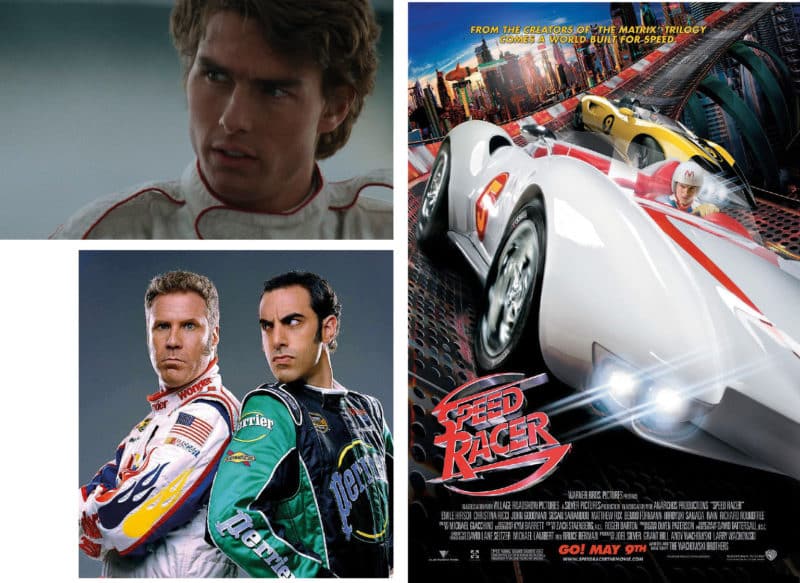

Days of Thunder (1990)

Days of Thunder

The 1990s provided even slimmer pickings. Tom Cruise’s “Top Gun on wheels” Days of Thunder was the big hit. Jackie Chan’s Thunderbolt the also-ran (although some suggest the plot-light stunt-heavy film may have inspired the Fast & Furious franchise). The Noughties began poorly with Sylvester Stallone’s flop Driven (“the worst car film ever made” according to Jay Leno) and got worse with a charmless Herbie reboot, Herbie: Fully Loaded starring Lindsay Lohan. In between was The Fast and The Furious, the first instalment of what would eventually become a billion-dollar franchise but here was in more modest form, becoming the 19th most popular film of the year and making stars out of both Paul Walker and Vin Diesel.

However, as film studios began to recognise that, for global box office returns, spectacle travelled better than story, the F&F series would become increasingly potent. 2006 brought the start of the Cars franchise. Pixar’s sport comedy series has fluctuated in quality over the years but here provides a solid first entry with Owen Wilson as the voice of the brash Lightning McQueen and Paul Newman as the retired Doc. As a Pixar film, it’s decidedly middle of the pack but as a racing movie for kids it more than succeeds. It was also Newman’s last film role.

Talladega Nights: The Ballad of Ricky Bobby (2006); Days of Thunder (1990); Speed Racer (2008)

Talladega Nights; Days of Thunder; Speed Racer

The absurd but frequently hilarious Talledega Nights: The Ballad of Ricky Bobby was 2006’s other racing movie. After hitting rock bottom and slowly rising back up, Will Ferrell’s Ricky Bobby – a NASCAR driver of dubious intelligence but undoubted driving skills – takes on Sacha Baron Cohen’s Jean Girard, an openly gay French driver. It proved to be one if Ferrell’s most successful films (behind Elf) and apparently a personal favourite of Christopher Nolan’s.

After a pair of underwhelming 2008 films – Jason Statham in a lacklustre remake of Death Race and the Wachowski’s misguided Speed Racer – the decade ended with the evocative and well-received Senna, Asif Kapadia’s documentary on the Brazilian legend.

Cars (2006); Senna (2010)

Cars, Senna

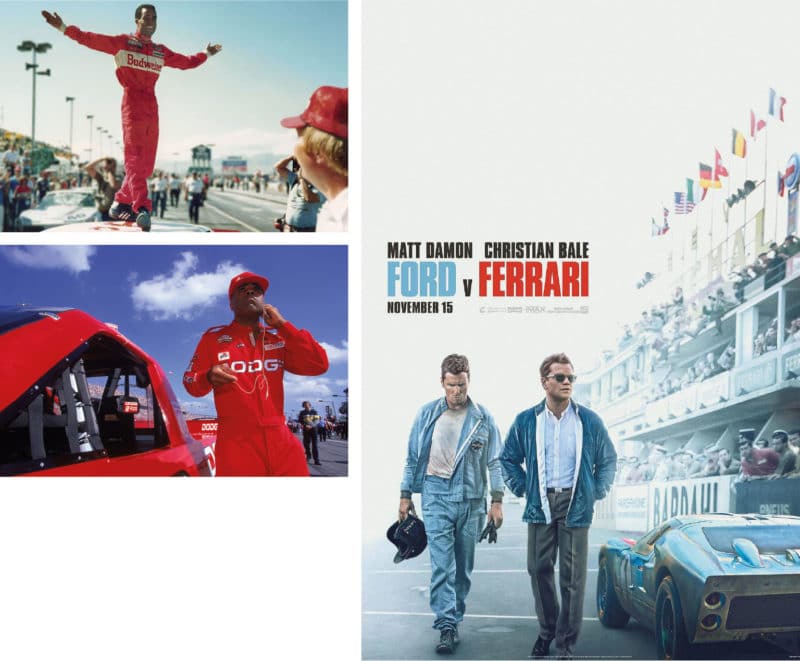

Rush; Ford v Ferrari

Rush; Ford v Ferrari

In recent years fans of racing movies have been blessed with riveting documentaries (2015’s Winning: The Racing Life of Paul Newman, and Steve McQueen: The Man & Le Mans are both worth a watch, as is 2020’s Uppity: The Willy T Ribbs Story) and compelling dramas. 2013’s Rush offered an exhilarating (if not always historically accurate) telling of the 1976 Formula 1 season and the legendary battle between James Hunt and Niki Lauda. It was one the best racing movies in decades. 2019’s Ford v Ferrari (Le Mans 66) was arguably even better. James Mangold’s sharp, measured take on how Carroll Shelby and Ken Miles created a legendary race car that could take on the Italians is an object lesson in film-making craft, anchored by fine performances from both Christian Bale and Matt Damon.

The bar for racing movies is once again set high. Will Michael Mann’s forthcoming Ferrari clear it? Time will tell. But either way, Hollywood’s going to keep making movies about fast cars and the people who race them. They’ve been doing it for over a century. Why stop now?

Scenes from Uppity; and the poster for Ford v Ferrari

Uppity, Ford v Ferrari