28. 1961 German GP: Moss masterclass is his final F1 victory

August 6, Nürburgring It was Monaco all over again. Always keen to take a gamble as an underdog, Moss had decided to start (from third on the grid) on Dunlop’s…

Jean-Pierre Prevel/AFP via Getty Images

TAKEN FROM MOTOR SPORT MAY 2019

Paul Newman had a strange request at the 1995 Daytona 24 Hours. The Oscar-winning actor and long-time racer had just turned 70 and was struggling to get in and out of the Ford Mustang he was driving in the US enduro. He was insistent that his team-mates manhandle him out of the car during pitstops to save vital seconds. The story reveals a lot about Newman’s attitude to his racing: he was fiercely competitive and wanted to be treated as an equal by team-mates and competitors alike.

“You had to climb in and out NASCAR-style with those cars,” recalls Tommy Kendall, the young hotshot in Roush Racing’s Daytona assault alongside Newman, NASCAR star Mark Martin and Mike Brockman in the GTS-1 class Mustang. “Paul felt like he was slowing up the driver changes and told us to grab him by the epaulettes and drag him out.

“I was thinking, he’s 70 years old and a national treasure, I can’t do that! But he was adamant. It showed how competitive he was, that he wasn’t there just to make up the numbers, and that he wanted to be treated as one of us.”

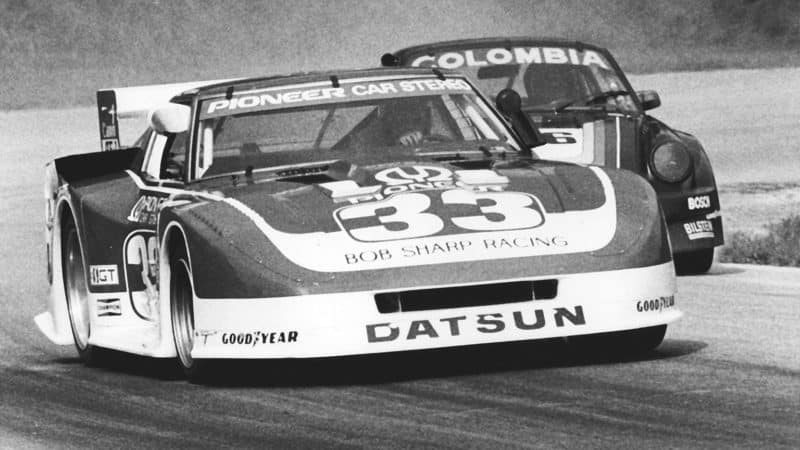

Paul Newman guides the Bob Sharp Racing Datsun 280ZX Turbo around a turn during a 1981 IMSA GT race

Getty Images

But that was Paul Newman the racing driver, or ‘PL Newman’ as he had originally designated himself when he set out upon what became a second career — as a driver and team owner — more than 20 years before. He didn’t play the big shot movie star in the paddock. Quite the reverse. He could and would talk for hours about racing, but the movie industry was off limits when he was in Nomex.

It was his starring role in the 1969 movie Winning that turned Newman onto the sport. His role as IndyCar driver Frank Capua involved driving the real thing, which explained why Universal Pictures sent Newman and co-star Robert Wagner to the Bob Bondurant Racing School in 1968 to get a handle on big, powerful racing cars. That whetted Newman’s appetite for the sport, an appetite he felt he’d better sate a couple of years later. A call to his local track in Connecticut, Lime Rock Park, resulted in a handful of hot passenger laps with Bob Sharp, a successful racer whose team was based just up the road.

“We would test at Lime Rock on a Tuesday, and sometimes the track manager would ask me to take someone around from this newspaper or that newspaper,” recalls Sharp. “One day, he asked me to take someone called Paul Newman and his son around. I didn’t really put two and two together. I thought all movie stars were 6ft 4in, but he was only 5ft 9in and came across as a regular guy in blue jeans. I had to ask someone else after we were finished it had actually been the Paul Newman.”

Newman in the paddock at the 1979 Le Mans 24 Hours. A Hollywood superstar he may have been, but he was never afraid to get his hands dirty

Jean-Pierre Prevel/AFP via Getty Images

The real thing visited Sharp at the Datsun dealership from which he ran his race team a couple of weeks after that. “He said, ‘I’ve wanted to be a race car driver ever since I did Winning,” recalls Sharp. “I would love to lease a car from you so I can go racing.”

Newman suggested that Sharp build him a racer around one of Datsun’s Z-cars, but the man who would become his racing mentor had other ideas. He told him that he should race one of the Datsun 510B saloons that his Bob Sharp Racing team was building, to learn his craft.

There was also the matter of securing a racing licence. The 510Bs weren’t ready, so he took a Sports Car Club of America course in a Lotus Elan borrowed from a friend of one of Sharp’s employees. There are stories that Newman won a race in this car at the Thompson Raceway in Connecticut some time in 1971. It remains uncorroborated, but Sharp believes it would have been no more than a school event.

Newman had a burning ambition to be a racing driver after filming Winning. And Bob Sharp gave him the platform to become one

Getty Images

Actor by trade, but racing driver by heart. Paul Newman wanted to prove himself on track, like everyone else. Newman quickly became a proficient club driver after joining Sharp in 1972 at the age of 47. He won the prestigious SCCA run-offs, an end-of-season event to determine the national champion in each of its amateur classes, for the first of four times in 1976. He won with a Triumph TR6 purchased from Bob Tullius (who would later mastermind Jaguar’s return to the Le Mans 24 Hours) in the D Production class at Road Atlanta during a short break from racing with Sharp. Newman was back with Sharp when he claimed his second run-off victory in 1979, this time aboard a Datsun 280ZX sports car. By then, he had taken his first steps in international motor sport. He’d raced at Daytona for the first time in 1977 at the wheel of a Ferrari 365 GTB/4, finishing fifth, again in the US 24-hour event in ’79 as a prelude to his one and only Le Mans assault.

By the following year he was racing regularly in IMSA’s Camel GT Championship aboard a GTU class 280ZX run by Sharp. But it was in the Trans-Am ranks that Newman enjoyed his greatest successes, the ones that prove how good he was. He scored two wins in the SCCA’s top professional category, one that ran to a single-driver sprint format. The first win came aboard a Sharp 280ZX at Brainerd Raceway in Minnesota in 1982 in what was a one-off for Newman. Second that day was Tom Gloy, an ex-Formula Atlantic champion and CART racer.

The field was more competitive when Newman took a second Trans-Am victory on his home track at Lime Rock four years later aboard a Nissan 300ZX. Among the drivers beaten by the 61-year old that day were Elliott Forbes-Robinson, Scott Pruett, Chris Kneifel and Wally Dallenbach Jr. The win wasn’t without controversy, though. Newman was running second to old friend Forbes-Robinson when the yellow flags came out in the closing stages. “There were yellows down the hill and at the last corner, and yellows at the first corner,” explains Forbes-Robinson, “but it appears that there were no yellows on the start-finish straight and Paul just drove straight past me as I backed off. That was a strange deal, but that’s OK because Paul and I were such good friends. It gave us a lot of laughs over the years.”

Forbes-Robinson had been instrumental in Newman becoming a team owner. He had been tutoring the movie star in the mid-’70s before getting his big break with Californian entrant Bill Freeman in single-seater Can-Am for 1977. Newman-Freeman Racing was established the following year, before morphing into Newman Racing in 1980.

The venture enjoyed its fair share of success. The runner-up spot with Forbes-Robinson in 1979 was sandwiched by fourth-place finishes and followed by another second position in 1981, this time with Italian Teo Fabi. The team closed after 1981 as the fortunes of Can-Am waned, but it opened the door to the formation of one of the most successful teams in North American single-seater history. Mario Andretti was the link between Newman and Carl Haas, the US Lola importer, ahead of the 1983 season. Andretti wasn’t happy at Patrick Racing in 1982 after his retirement from Formula 1, and engineered the new partnership for the burgeoning CART series.

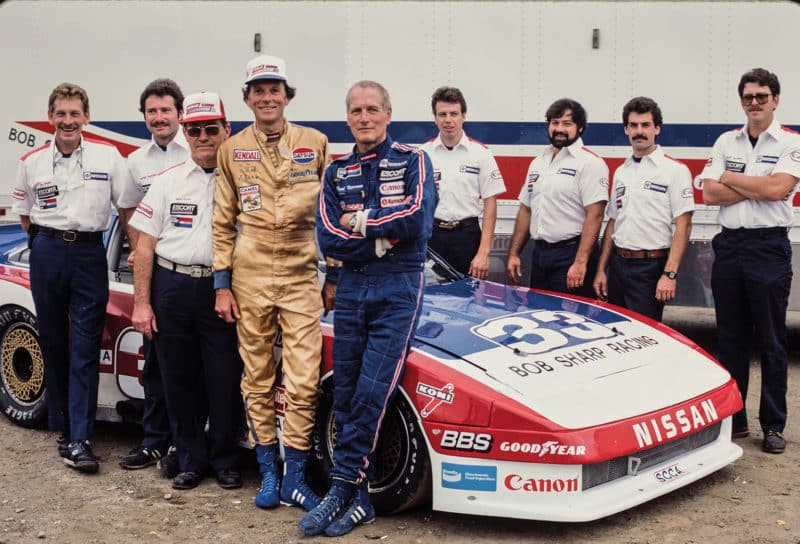

Newman spent a large portion of his driving career competing with the Bob Sharp Racing team in a range of Datsuns, each one gaining in power as he worked toward larger races, such as Daytona and Le Mans

Getty Images

Andretti had become friends with Newman after meeting him at a race in the original Can-Am series at Bridgehampton on Long Island in 1967. He was driving a car called ‘the Honker II’ built by Holman & Moody for Ford, who brought Newman along as a guest. As well as putting his name on the front of a machine Andretti calls “the worst car I ever drove”, Newman was given a passenger ride by Andretti. “Paul and I always stayed in touch,” recalls Andretti. “He invited me to drive one of his Can-Am cars at one point, but I was still doing F1 and it didn’t fit my schedule.

“I had a meeting with Carl and asked him why didn’t he come and do IndyCar and brought up the idea of bringing in Paul as a partner,” he says. “Then I went to Paul and asked him if he had ever entertained the idea of running Indycars. He was interested, but when I told him I was talking to Carl, he said, ‘Hang on a minute.’”

There was a bit of history between the two from their days as rivals in Can-Am. The Freeman-run team hadn’t had an entirely cordial working relationship with Haas Enterprises, not in the early days of single-seater Can-Am with the Lola T333CS, which Freeman re-engineered into what it called the Spyder, nor when it ordered its successor, the T530 for 1980. It quickly switched to March chassis for the following season.

“It wasn’t a marriage made in heaven, but it turned out like one,” says Andretti. “I thought there would be strength in numbers having Paul and Carl, and I knew Paul would be a good draw for sponsors.”

Newman/Haas Racing was born with an initial five-year deal between the two principals for the CART programme. Andretti was a race winner in year one in 1983 with the initially recalcitrant Lola T700, which carried Budweiser sponsorship secured by Newman. The following year, he won the title. Seven more would follow for the team prior to the demise of what had become the Champ Car World Series in 2007. The team claimed a total of 105 race victories and two more in the IndyCar Series before the team shut at the end of the 2011 season, three years after Newman’s death.

Newman was ever present in the team set-up. A regular at the races, he brought much more than just his name.

“Paul was a major asset to the team and to our sport,” says Andretti. “I saw him as an ally when I needed someone to push the button to make things happen. He also helped us recruit the best possible people.”

Newman’s second career in motor sport also led in a roundabout way to his third – in the food business. Newman’s Own, founded to produce salad dressing, was established after an introduction from Sharp.

“Paul would always flip the burgers on a Saturday night at the track when the guys were working on the car,” says Sharp. “He’d bring some of the salad dressing that he made every Christmas with his neighbour, the author AE Hotchner. One day, he says, ‘Sharp, I wanna to go into the salad-dressing business.’ I told him he was crazy, but he wanted to do it, so I introduced him to a friend of mine who ran grocery stores. Once the dressing was given the seal of approval by another of Sharp’s friends, the owner of a chain of steak houses, the retailer placed a first order in 1982, and Newman’s Own was set up. The not-for-profit company has since donated more than $500m to charity.

Somehow Newman managed to find the time to race alongside team ownership and selling salad dressing, not to mention maintaining a successful film career. He stopped racing Trans-Am after 1988, but continued to appear sporadically in IMSA events. His assault on Daytona in ’95 came courtesy of Paramount Pictures, which was promoting Nobody’s Fool. It paid for the deal, and paid handsomely, according to Kendall.

“Roush had won Daytona in class nine times in a row before sitting out ’94,” recalls the four-time Trans-Am champion. “Paul rang the shop and asked the team manager at the time, Max Jones, how much it would cost to run a car. Like you do when you don’t want to do something, you come up with a figure that no one in their right mind would agree to. Paul just said, ‘Fine, Paramount is paying for the whole thing.’”

Newman, Kendall, Martin and Brockman won their class and finished third overall with the number 70 on the side, in honour of its star driver’s age. Newman would request that the race number on his cars reflect his age for the remainder of his career – and remarkably that continued into his eighties.

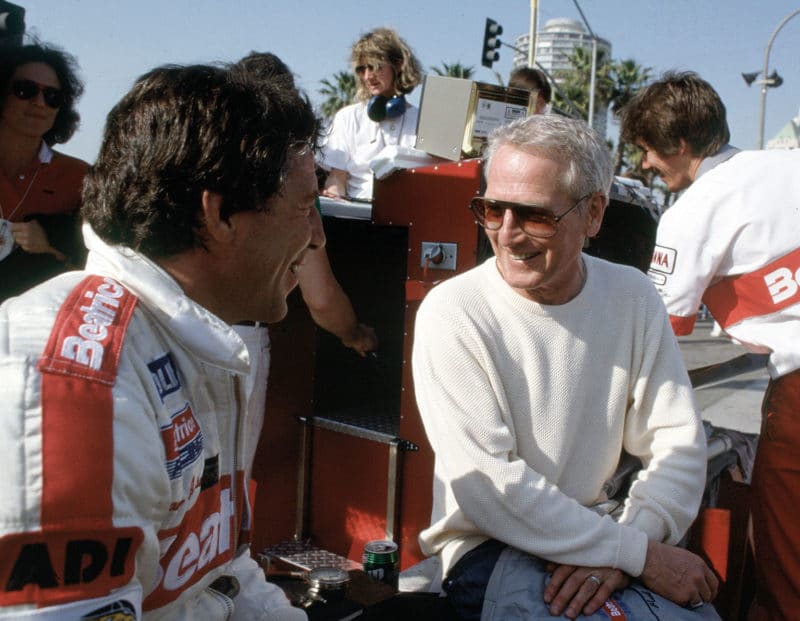

Mario Andretti and Newman were close friends, and Andretti even proved to be the link that helped found Newman/Haas Racing in IndyCar

Getty Images

Newman returned to the SCCA ranks with a series of Trans-Am cars run out of the back of a Volvo dealership owned by Brockman, a friend and fellow actor who’d raced Formula 5000 back in the 1970s and was now his right-hand man when it came to racing. A Nissan was followed by a Chevrolet and then a Jaguar, in which Newman made his last appearance at the Run-Offs in 2002.

But Newman wasn’t done with international sports car racing, despite his advancing years. Back in 1987, he’d met team owner Kevin Jeannette at Riverside and it resulted in a brief run in a Porsche 962 entered by Primus Motorsports.

“We were replacing the clutch and needed someone to give the car a quick run, and neither of my drivers was there,” recalls Jeannette. “I saw Newman riding around on this little fold-up bicycle, called him over and asked him if he wanted to drive. He told me that Chris Kneifel [one of the drivers and the car’s owner] had promised him that he could drive it any time he wanted.”

When the allotted time came for the ad hoc test, Newman was nowhere to be seen. It turns out that he and Kneifel had regularly played practical jokes on each other in their days on the Trans-Am trail, and Newman suspected this was another.

“Newman told me that he thought I was kidding because it was Kneifel’s car,” says Jeannette. “When I said I wasn’t, he jumped on that little bike and pedalled away in fast motion. He was back in a couple of minutes with his Nissan overalls on.”

After that Jeannette would regularly invite Newman and Brockman down to Florida to play in some of his Porsches, which resulted in a return to Daytona in 2000. He drove a Porsche 911 GT3-R entered by Champion Racing in what was the first of four appearances in the 24 Hours past his 75th birthday.

The last came days after he turned 80 in 2005. Newman raced a Ford-powered Crawford DP03 bearing sponsorship from the Pixar movie Cars. What it didn’t carry was race number 80.

“Another team had that number and wouldn’t give it up,” recalls expat Brit Chris Hall, whose Silverstone Racing team ran the car, “but we were allowed to run as 79+1.”

Hall recalls being impressed by the oldest driver ever to race at Daytona. “I don’t remember him being more than a couple of seconds off the pace,” he says. “Daytona isn’t a very demanding track, but that’s still pretty amazing for an 80-year-old.”

Ten years before, Newman had been much closer to the pace. “Paul wanted the lap time records after the race,” recalls Kendall. “I was the lead driver and the quickest guy, but I’m going to say that on average he wasn’t much more than a second behind me at any point.”

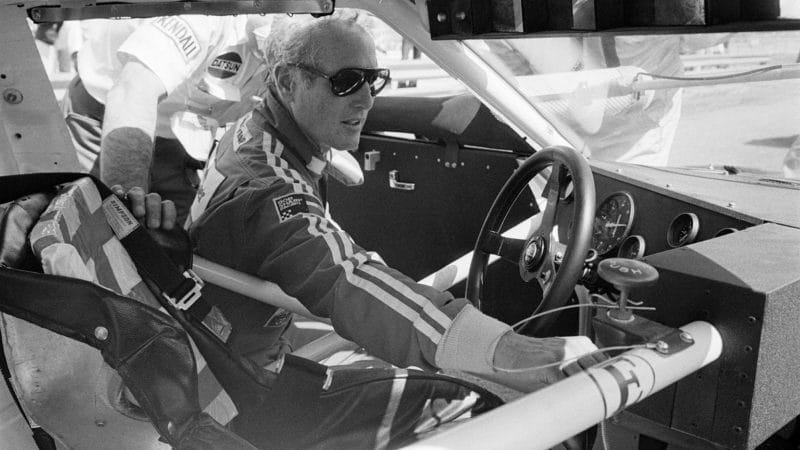

Paul Newman makes some last minute checks on his Bob Sharp Racing Datsun, before the start of the Los Angeles Times Grand Prix of Endurance at Riverside

Newman was a talented racing driver, although he would never have admitted it. He always played down his abilities. I approached him during one of his later Daytona appearances, wanting to talk about Le Mans in ’79. My request was politely turned down. “Nah,” he said. “I didn’t drive very well that day.”

Dick Barbour, who ran the Porsche he and Newman shared with Rolf Stommelen, reckons that wasn’t true. “Paul did a good job in difficult circumstances,” he says. “It was something he worked very hard at, and his lap times were very consistent.”

Newman had a hunger for success that was backed up by a healthy work ethic. “Paul was always asking, ‘Tell me what you think here, tell me what you think there,” says Forbes-Robinson. “He’d do anything to get himself going faster.”

Sharp says that Newman had a “burn in his belly”. He has no doubts that the actor could have been a professional racer if he’d started 20 years earlier. “I’m better at telling you how good he was as a driver than he would have ever been,” reckons Sharp. “He would have said, ‘Well I was OK.’ That wasn’t true. He beat all those young lions left, right and centre.”