Lunch with Jacky Ickx

He may be his own man, but Ickx doesn’t like discussing his own achievements, preferring instead to acknowledge the efforts of those around him. But all those Le Mans wins, those Grand Prix heroics in the wet – they can’t be ignored

Porsche Archives

Each month for the past five years it’s been my privilege, on your behalf, to take a motor racing name to lunch. Then, on these pages, I’ve passed on to you the intimate details of our conversation. The 64 personalities so far have spanned six decades, and have ranged from the extrovert to the shy, from the proud to the modest. Without exception all have been remarkably open and honest. Beside a string of great drivers, including eight World Champions, other disciplines have been covered: team owner, designer, mechanic, circuit boss, Formula 1 doctor, Land Speed Record holder, FIA president. All have been happy to tell me about the achievements in their lives that have meant most to them.

But Jacky Ickx is different. As a working race reporter and broadcaster, I knew him quite well during the 20 years of his brilliant career in F1 and sports cars. He was an eight-time Grand Prix winner for Ferrari and Brabham, and twice runner-up in the World Championship. And he became the most successful endurance racer of all time, supremely fast in darkness and in rain, with six Le Mans victories and countless other sports car wins to his name. Above all I knew him to be an individualist: always friendly and courteous, but a man not afraid to speak his mind and stand by his principles, even when they separated him from the rest.

A fresh-faced lckx

Getty

When I ask to take him to lunch, he is happy to accept, but insists – with surprising passion – that he is not interested in describing his own achievements. “I do not want to be talking all the time about me, myself, I. Motor sport is a selfish sport, but every victory is like an iceberg. The small part of the iceberg that is visible is your drive in the race, it receives all the glory. But under the waterline is the majority of the iceberg: the mechanics of course, but also the talents of the people back at the factory who designed and built the car. Most of the winning is done before the car even gets to the track: the driver is just there to finish the job. As a driver you may become famous, and nowadays you may also become very rich. But you are only the final link in a long chain of many people who live in the shade, who work hard to do their jobs right, and who get their satisfaction when the whole combined enterprise achieves what it was striving to do.

“I only have one regret, looking back on my time in motor racing. In those days I was a sort of monorail, I was always thinking about myself and about winning. That is what it is like when you are a racing driver: mentally you are not very grown-up. I respected the people who helped me, of course, and I always had the courtesy to say thank you to them. But I regret not being more aware of all the links in the chain. The victories were theirs, not mine; but I was not big enough intellectually to see it. Now I have grown up, I have more of a 180-degree vision. So that’s why I will have lunch with you: to give myself a chance to acknowledge publicly what I owe.”

In full flow aboard a Cortina in the ETCC at Zandvoort,1965

Getty Images

As the Eurostar pulls into Bruxelles Midi station, Jacky is waiting for me beside his Audi A8. Rather than nominating a favourite restaurant, he insists on welcoming me to his home in the centre of the city, a superb period town house with high walls hung with African art – but not a single racing picture or trophy – and a lush walled garden. There his tall and beautiful wife, the Burundi-born singer Khadja Nin, serves a superb meal combining cuisines from Africa and the Far East: rice with spices, endives in sugar, chicken with coconut, beans with onion and garlic, mango and raw mint.

“My time in cars was a different life. When I am shown pictures of me in races, I hardly recognise myself.” But little by little I persuade Jacky to delve into his memories of his racing days, although much of what follows comes from what I witnessed at the time, because either he has forgotten many of his great races, or prefers not to talk about them.

Despite being born into a car-centric household – his father was the Belgian motoring journalist Jacques Ickx – as a child Jacky had no interest in racing. “Aged 10 I was taken to Spa for the 1955 Belgian Grand Prix, and saw Fangio and Moss in their W196 Mercedes. But it didn’t excite me at all. At school my results were always poor: I liked to sit at the back of the class, near the window and the warm radiator. My parents had no idea what to do with me. When I was 15, with my school results a disaster and my teachers saying I was good for nothing, my father bought me a 50cc Puch motorcycle. It was pure destiny. At last I discovered something I wasn’t bad at.

“By the time I was 16 I was doing trials and the results began to come” – he was rapidly crowned European Champion in his class – “and then I was offered rides by works teams. I suppose I am one of the few Belgians to have done the Scottish Six Days Trial. On two wheels on those steep, slippery surfaces I learned a lot of lessons about balance, which probably helped me in wet-weather racing later. I moved into circuit racing on Kreidler and Zundapp – all nine-speed gearboxes and 20,000rpm – and then I was lent cars to race: a BMW 700 coupé, then a Cortina.” Having won the Belgian Touring Car Championship, Jacky began to attract attention outside his home country, in particular from Ford, which led to outings in works Cortinas and the ex-Alan Mann Mustang. At the 1964 European Touring Car round in Budapest Ken Tyrrell, running the works Mini-Coopers, noticed the speed of a Lotus-Cortina driven on the wheel-waving limit by a teenager with a wide smile.

Ickx wanted to use his interview to thank the many people who helped him during his career

Getty

He summoned Jacky to Goodwood for a test in an F3 Cooper. Jacky crashed the car, but beyond the minor damage Ken saw in the youngster remarkable natural talent, and a true racer’s spirit. So he ran him in an F3 Matra in 1966 at Monaco, and then at Silverstone in July. Most of the day’s top Formula 3 names were there: Irwin, Gethin, Oliver, Bell, Nunn, Beckwith, Lucas, Crichton-Stuart. Having practised out of session Jacky started at the back of the 30-car grid, and in pouring rain he sliced through the field, passing cars right and left, to finish an astonishing third. It was many people’s first sight of Ickx in the wet: he doesn’t recall this race, but I certainly do.

“Many people helped me, but Ken and Norah Tyrrell were the most important”

But Jacky holds the memory of Ken Tyrrell and his wife Norah in great affection and respect. “So many people helped me in my racing, but Ken and Norah were, without doubt, the most important. One of my memories is going to a test at Oulton Park in a van from Ken’s timber yard with the car in the back, singing Beatles songs, We all Live in a Yellow Submarine, and Ken was singing too.” Rapidly promoted to Formula 2 in the Matra-BRM alongside Jackie Stewart, Jacky ran in the F2 section of the German Grand Prix. His 1-litre car qualified quicker than two of the F1 entries, and 8sec faster than the next quickest F2 runner, although his race only lasted one lap. Three weeks earlier the still-unknown youngster had his first race at Brands Hatch in the sports car race supporting the British Grand Prix, in a 6-litre McLaren-Chevy owned by Alan Brown. He qualified it on the front row alongside Richard Attwood’s Lola T70 and Chris Amon’s McLaren, spun, but fought back to finish fifth.

In 1967, in the now 1600cc F2, Jacky did a full season for Tyrrell’s Matra team alongside Stewart. He was a sensation, taking the European Trophy – effectively the F2 championship, but excluding graded drivers – and winning at Crystal Palace, Zandvoort and Vallelunga. Still only 22, he showed he could race competitively against Clark, Stewart, Rindt, Surtees and the rest. But the race that really put Jacky at the top of many F1 team managers’ shopping lists was the German GP. Once again F2 cars were admitted to make up the numbers. In practice Jacky dumbfounded everybody with an 8min 14sec lap in the little Matra, which for a long time was fastest of all. Eventually the F1 cars of Jim Clark and Denny Hulme (just) went quicker, but he remained third-fastest qualifier, although he had to start with the other F2 cars at the back. At the end of the first lap he was 12th; at the end of lap three he was fifth – having set a new outright lap record. On lap five he came through in fourth place, ahead of Amon’s Ferrari and Surtees’ Honda. Amon did get by him again later, and both Hulme and then Gurney took a bit off his lap record, but Ickx was still in fifth place when, with three laps to go, a ball-joint broke on his front suspension.

“I was still living at home. My mother would say ‘don’t drive too fast’ before races”

Typically, Jacky is self-deprecating about that drive. “It was funny because a lot of people had still never heard of me. And with my name, it was like I was called Monsieur X, a mystery man. But you have to remember, at that time the Nürburgring was very difficult in a Formula 1 car. There were 17 different places each lap where we used to get off the ground. So a properly set-up F2 car had an easier time. Also I had twice done the Nürburgring 84 Hours, in a Mustang and then in a Lotus-Cortina, both times with only one co-driver.

Ickx at Brands Hatch with Ford GT40 (and girlfriend Peta Selcombe) before the start of the 1968 BOAC 500

Getty Images

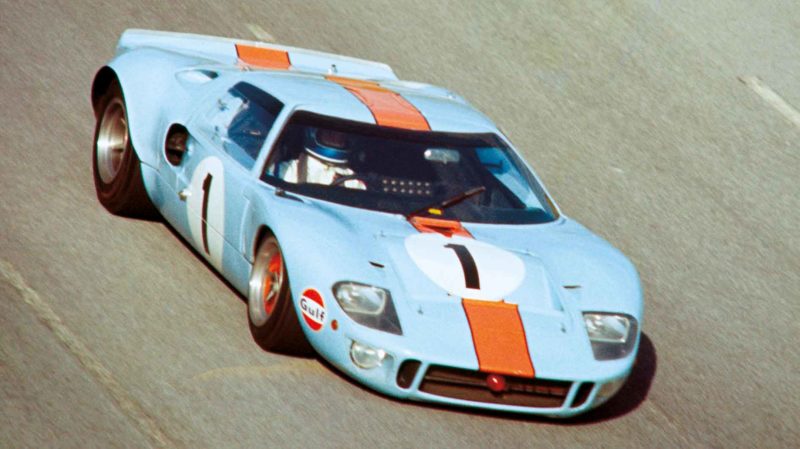

1969 Daytona 24Hrs with JWA

Getty Images

So I really did know every centimetre of the track. Jo Bonnier, who was head of the Grand Prix Drivers’ Association, said I must not be allowed to start from the front row, because I would get in everybody’s way and it would be dangerous. That did me a good turn, made it look better because coming up from the back I was overtaking all these F1 cars in my little Matra.” Jacky passed Bonnier’s Cooper-Maserati on the first lap.

His first race in a proper F1 car came a month later, at Monza. “I think Ken suggested me to Roy Salvadori, who was running the Cooper-Maserati team. Jochen Rindt was the number one driver there, and he was very helpful to me while I learned the car.” In the race Jochen, in the lighter T86, was fourth; Jacky, in the unwieldy old T81B, was sixth, scoring a championship point in his first true F1 drive. By now he knew where he was going for 1968.

Jackie Stewart, anxious to move on from BRM, had been approached by Ferrari, and after two meetings with Enzo believed a deal was done for the ’68 season. According to Jackie’s 1970 book World Champion, “Ferrari was just what I was looking for. Next thing I heard was the drive had been offered to Jacky Ickx because I had asked for too much money.” At the same time Ken Tyrrell was setting up his own F1 operation to run the DFV-powered Matras, so Stewart duly signed for him. Ken would have liked Ickx as Stewart’s number two, but Matra wanted a French driver in the team, so Johnny Servoz-Gavin was signed.

“If life had decided differently, I would have loved to stay with Ken. Matra had all that aircraft and missile technology, the Ford DFV was the best engine. But [Ferrari team manager] Franco Lini was sent to the August F2 race at Enna in Sicily to speak to me, took me to Modena to meet Enzo Ferrari, and I signed. You can imagine how I felt, at 22 years old.”

It was barely two years since Ickx had been racing a Cortina in Belgian clubbies. “I was still living at home. When I went off to a race my mother would say, ‘Jacky, be careful, don’t drive too fast.’

“I drove for the Scuderia for five of the next six seasons. For me they were great, great years. You hear many former Ferrari drivers making mixed comments about their time there, but I was well-treated at Maranello. Yes, there were arguments sometimes, like in any team, but I always felt I had the same cars and opportunities as my team-mates. Enzo Ferrari himself was careful not to get too close to his drivers. I think he was protecting himself, because it must have been very painful for him down the years to lose talented people from his F1 team: Ascari, Castellotti, Musso, de Portago, Collins, von Trips, Bandini – it is a sad list. It may surprise you, but to me he was a very sensitive man, tender even. I think I did have a special relationship with him – I am one of very few drivers who left Ferrari, and was asked back.”

In the hot seat of a Ferrari 312 at the Italian GP in 1968

Getty Images

His first F1 victory came in the ’68 French GP at Rouen which, unsurprisingly, was soaking wet.

Getty Images

During 1967 Jacky had also begun a fruitful relationship with John Wyer’s JW Automotive sports car team. In the Spa 1000Kms in JW’s updated GT40, the Mirage, he demonstrated not only his knowledge of the circuit but also his speed in dreadful weather, driving almost single-handed to win in heavy rain. He won the Montlhéry 1000Kms with Paul Hawkins, again in the wet, and then the Kyalami Nine Hours with Brian Redman. The following season Jacky’s JW GT40 won three rounds of what was effectively the World Sports Car Championship, with Redman at Brands Hatch and Spa and with his countryman Lucien Bianchi at Watkins Glen. Spa was almost flooded from the start, and at the end of the first lap Ickx’s lead over the rest was 39 seconds…

Meanwhile his first full F1 season had been going superbly. At Spa he qualified on the front row and, despite a misfire, put it on the podium. He was fourth at Zandvoort. Then at Rouen, in only his fifth Ferrari Grand Prix, it rained heavily and he came into his own. On a waterlogged track his speed was sensational, and he led virtually from start to finish, to score Ferrari’s first Grand Prix victory since Monza 1966. More podiums at Brands Hatch and Monza left him lying second in the Championship, three points behind Graham Hill with three races to go.

But during Friday’s practice for the Canadian GP his throttle jammed open just before a fast right-hander. The car flew a long way before destroying itself against St Jovite’s fences, and his injuries included a broken leg and facial wounds. He was back for the final round in Mexico with a metal brace on his leg, but ignition trouble stopped him, and he slipped to fourth in the championship. “But I never thought about the championship, or about the points. It was the races that mattered. Like Stirling Moss, I just wanted to win each race.”

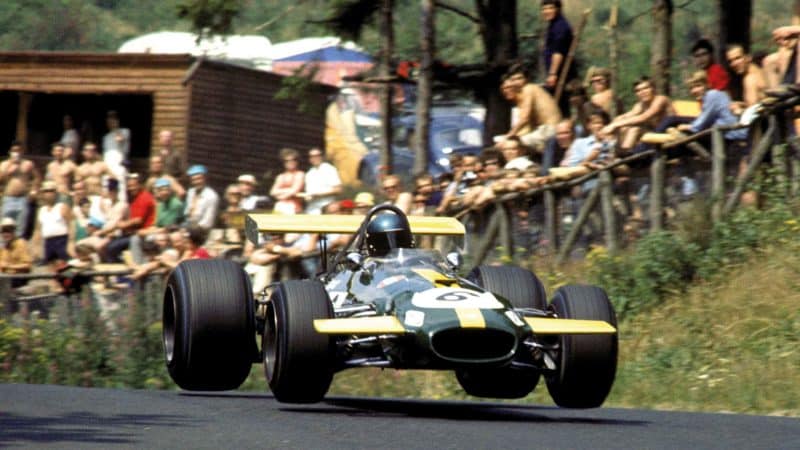

It was a surprise when Jacky left Ferrari to join Jack Brabham’s F1 team for 1969, but this allowed him to continue with his JW sports car contract. Stewart dominated F1 that year with the Matra, while at first the Goodyear tyres used by the Brabhams lacked the dry-weather speed of their Dunlop and Firestone rivals.

But after third at Clermont and second at Silverstone, Jacky put his BT26 on pole at the ’Ring. At the end of the first lap he was only fourth, but then began one of the drives of his life – in the dry this time – as he climbed past first Rindt and then an on-form Jo Siffert in Rob Walker’s 49, winding in Stewart relentlessly and taking an extraordinary 21.4sec off Stewart’s own lap record. On lap seven the Brabham passed the Matra going into the South Curve, pulling away to win by almost a minute.

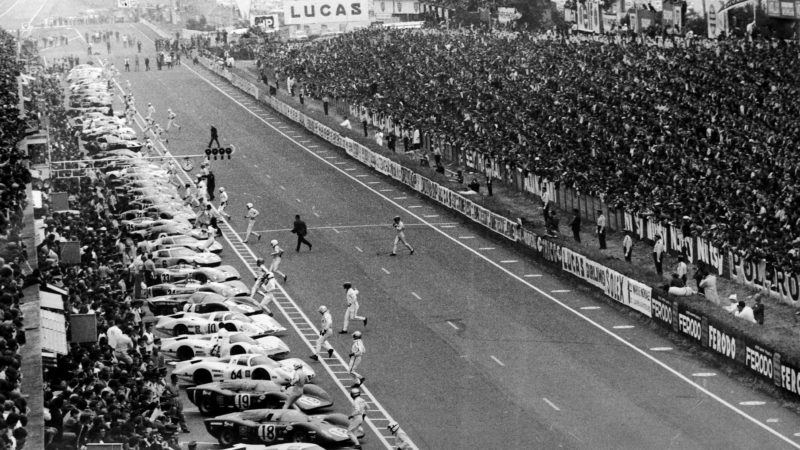

Ickx walking during that infamous Le Mans start

The following month Jacky won the Canadian GP after a controversial incident when, battling with Stewart as they lapped a backmarker, the two cars touched and Stewart retired with a broken wheel. After the race Ickx apologised, publicly and to Stewart personally. The season ended with Stewart champion, and Ickx runner-up. In those days Jackie Stewart was vociferous in his efforts to improve motor-racing safety, but Ickx created much controversy by resigning from the GPDA, saying its threats of boycotts and strikes were uncivilised.

“Jackie and I meet often now, we are good friends. Now we can call ourselves survivors, and any of the disagreements we had 40 years ago look ridiculous. But I have to say that, for a while, we disliked each other deeply. I was not against the idea of improving motor-racing safety: that would have been foolish. My problem was with Jackie’s methods. I was conservative; I accepted the risks without argument or discussion. You have a steering wheel in your hands, you are happy. You win, you are even happier. Can you imagine, back then, stopping a race because the conditions were too wet? No driver would think of such a thing for a single moment, it was part of the job. And the job’s not meant to be easy. If you win without difficulty, you win without glory.

“But, of course, the dangers were constant at that time. For those of us who did survive it was not a matter of talent, because many talented people didn’t make it. It was a matter of luck. We lost Courage, McLaren and Rindt in ’70, Giunti, Rodríguez and Siffert in ’71. It didn’t change my attitude to racing at all, but often when I shut my front door leaving home for a Grand Prix it went through my mind that maybe I would not be back to open that door again after the weekend. I’m sure it was the same for every driver. In the car there was no room to think about having a mechanical failure, but the thought was buried in your mind somewhere. We were still in the era of straw bales, and the FIA was not taking care of making things better. Jackie was the first to focus on safety, with Jochen Rindt as well: the two of them worked on it together. But Jochen did not survive. Jackie is the man who changed racing, and for that a whole generation of drivers must be grateful.”

“I did have to run the last few metres for that Le Mans start, otherwise I would have been run over”

At Le Mans Jacky was prepared to make his own demonstration: no boycott, no ultimatum, just a statement that would affect only his race. Almost all racing drivers were now wearing seat belts, but the 24 Hours still started as it had done since the 1920s, the cars lined up in echelon on one side of the road and the drivers running across to jump in, start up and drive off. Most drivers would struggle into their belts at speed during the first lap: some didn’t wear them at all for their first stint. Jacky felt this was stupid, so when the flag fell and everybody else sprinted across the road he walked deliberately across to his car, got in, did up his safety harness, and then departed dead last. “In fact I did have to run the last few metres to my car, or I would have been run over! A lot of people were upset with me, because that start was a great Le Mans tradition.”

And there was a dreadful accident on that first lap, when John Woolfe lost control of his Porsche 917 in the old high-speed kink at White House. In the closely packed mayhem just after the start, several cars were involved. Chris Amon was lucky to escape unhurt from his burning Ferrari after it hit the Porsche’s dislodged, and full, fuel tank. Woolfe died in the accident.

Winning Le Mans in 1969 in the closest finish ever

Getty Images

fter four hours Ickx’s JW GT40, shared with Jackie Oliver, had climbed from the back of the field to seventh place. By dawn on Sunday morning it was third, and by 11am it was in the lead. But in the closing stages it was caught by Hans Herrmann’s Porsche, and a flat-out wheel-to-wheel battle ensued, Ickx forced to go 1000rpm above his conservative 6000rpm rev limit as he tried to calculate how to manage the final lap. He decided to let the Porsche lead out of Tertre Rouge, so he could slipstream past on the Mulsanne Straight and stay in front to the flag. It worked, and he crossed the line a few lengths ahead of the Porsche in the closest finish in Le Mans history. He admits now: “It would not have looked good if I had lost the race by the amount I used up in my demonstration at the start. But fortunately, like all the best stories, it had a nice ending.” And the next year the traditional Le Mans start was gone.

For 1970 Jacky was back with Ferrari, to conduct both the 312B F1 car and the big 512S in sports car races. In the season’s second Grand Prix at Jarama, on the opening lap, Jackie Oliver’s BRM lost its brakes and T-boned Ickx’s Ferrari, rupturing its full fuel tanks. Both cars were engulfed in fire: Oliver got himself out, but Ickx could not. His life was saved by the prompt action of a Spanish policeman, who went into the fire and dragged him out of the wreck. “That man from the Guardia Civil beat out the flames in my overalls with his hands, and he got burned too. Later I spent months trying to thank him, but I could never find him. I was burned on the face, hands, back, legs. When I turned up for the Monaco Grand Prix three weeks later I was a horrible sight, all strapped up and covered in grease. Burns are the worst thing. But you recover. It didn’t affect me at all.”

In fact, Jacky went on to have another great Grand Prix season, with three victories, four poles and four fastest laps. But Rindt’s string of five victories put the Austrian well ahead in the championship, until the dreadful tragedy of his death at Monza. By winning two weeks later in Canada, Jacky was now second in the table with two races to go. If he were to win at Watkins Glen and Mexico City it would prevent Rindt from being posthumous World Champion. “That was absolutely not what I wanted. Winning the title like that would have been no pleasure.” He must almost have been relieved when, running second to Stewart at Watkins Glen, a ruptured fuel pipe put him out. That left Rindt’s total unbeatable, even though Ickx did win the final round in Mexico.

Jacky’s best race in 1971 was the Dutch Grand Prix, when he fought and won a torrid battle with Pedro Rodríguez’s BRM, and lapped the rest of the field. It rained almost throughout, and a March blew its engine and clanked on for half a lap, covering the track with oil: yet another example of Jacky’s genius in slippery conditions. I suggest that he must have welcomed rain, because it gave him a clear advantage. “No, no, you are totally wrong. I hated the rain, because the dangers were multiplied. But maybe it disturbed other drivers more. If everybody believes you are good in wet conditions, perhaps they give up more easily, they let you go.”

Ickx marked himself out a master of the Nürburgring. He won the 1969 German Grand Prix with Brabham

Getty Images

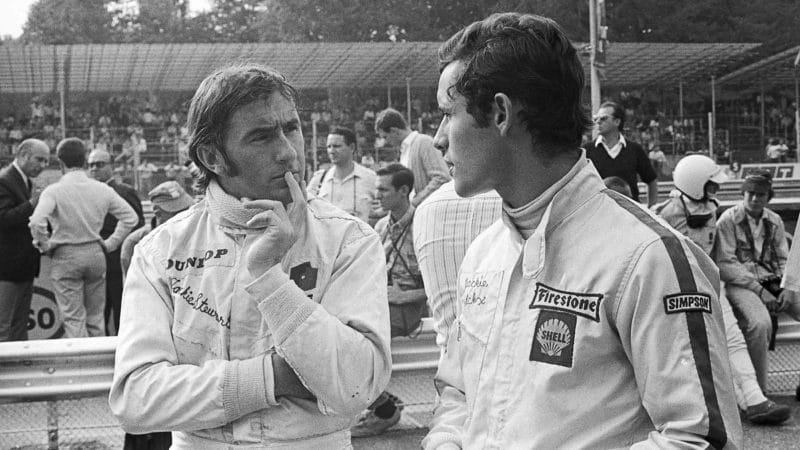

With Jackie Stewart in 1968

Getty Images

The flaming wreckage of Ickx and Oliver’s cars at Jarama in Spain, 1970

Getty Images

The 1972 German GP was vintage Ickx, starting from pole, leading from start to finish, and taking another 6.5sec off the Nürburgring lap record. But the rest of the season, despite three more GP poles, was ruined by unreliability: he retired from the lead at Brands and Monza, and from second place at Nivelles and Clermont. Things got worse at Ferrari in 1973, and the bulky B3 was both heavy and uncompetitive. After qualifying a depressing 20th at Silverstone, Jacky agreed a release from his contract with Enzo Ferrari. He had one-off drives for McLaren (finishing a strong third at the ’Ring) and Frank Williams – with one more Ferrari ride at Monza – before signing for Team Lotus for the ’74 season alongside Ronnie Peterson.

It was not a happy time at Lotus either, Jacky swapping between the unpredictable 76 and the now elderly 72, although he does remember fondly his victory in the 1974 Race of Champions at Brands Hatch. Once again it was a win in heavy rain, and it included in the closing laps a famous overtaking manoeuvre on Niki Lauda’s Ferrari, around the outside of Paddock Bend. “At Lotus Colin Chapman was a legend, but I cannot say I was close to him, because Ronnie was really the number one. But Colin loved very much that Race of Champions win. I made one attempt to pass Niki at Paddock and luckily he did not see me, so that got in my mind how it could work on the next lap. If he had seen me maybe he could have stopped me coming around him. But in rain you are quite busy at Paddock Bend”.

By mid-season in 1975 Jacky had left Team Lotus, and the rest of his F1 career, with Frank Williams and then Morris Nunn’s little Ensign team, brought no joy. In the 1976 US GP at Watkins Glen his Ensign charged the barriers head-on and caught fire. Jacky escaped with fractures to both ankles and burns.

“The car was cut in two. They decided to take me to hospital in Elmira, but on the way they had to stop at a gas station to put petrol in the ambulance. We were in the amateur days then.”

Over the next two years he did isolated races for Ensign, but his F1 days seemed over. Then in 1979, while he was driving for Porsche in sports cars and for Carl Haas in America – winning the Can-Am title in a LolaT333CS – Ligier driver Patrick Depailler was injured in a hang-gliding accident. So he was drafted in alongside Jacques Lafitte. “I thought it might be an opportunity to make an F1 comeback. But I found I was usually three or four tenths slower than Jacques. There may have been reasons for that, but I felt inside myself no capacity to go any faster. It’s never pleasant to say to yourself, ‘I am not as good as I was before’. You try to find excuses, say you will have a better race tomorrow. But I have always been honest with myself. I understood I was never going back to the front of F1. When you know that, the decision is easy. You pick up something else where you can get the motivation. I was still winning sports car races, but in that type of racing, if you are in a good car with a good partner, there isn’t the same pressure, nor the same level of opponents.”

Ickx ready for action in a works Porsche 956 at Le mans in 1982

Getty Images

In sports car racing Jacky’s record continued to be extraordinary. While at Ferrari he had won races in the jewel-like 312P, effectively a two-seater streamlined F1 car, which Jacky remembers as “a lovely toy, very easy to drive”. In 1972 alone he won Daytona, Sebring, BOAC Brands, Monza, Zeltweg and Watkins Glen. In ’75 he drove for all three top sports car teams, winning Spa for Matra, and also racing for Alfa and Mirage. By 1976 he had begun his long and highly successful relationship with Porsche, for whom he scored four of his six Le Mans victories and some two dozen other major wins over 10 seasons. During his career he scored nearly 50 victories in international endurance events.

“But that’s something else that is not down to you, because you are nothing in sports car racing without a co-driver. Derek Bell, Jochen Mass, Mario Andretti, Brian Redman, Jackie Oliver – those five in particular, we shared the same goal, we did the same job. You relate so closely with your co-driver: he comes in during the night, jumps out, it needs only a few words – how is the track, what is the feeling with the car, pay attention to this little noise. In 1975 Derek and I did half of Le Mans with a broken chassis on the Mirage. On every corner there was a grinding from the back. We dealt with it together, and we won.

“And 1977, that was the most extraordinary Le Mans for Porsche. I was sharing a 936 with Henri Pescarolo, but after four hours the engine blew. The other 936, driven by Jürgen Barth and Hurley Haywood, lost a lot of time changing a fuel injector pump. They were 41st. I was put in that car as reserve driver, and we all three had to drive flat out for 20 hours.” With Ickx doing the lion’s share, the Porsche was back up to ninth place by 9pm, and by 3am it was third. By 10am on Sunday it was leading. “It was good to see the impact on the team as we climbed up the classification, place by place.” Then in the final hour, dismay: the car came smoking into the pits with a burned piston. The mechanics disconnected the valve-gear on one cylinder and turned down the turbo boost, and at 3.50pm it chugged out for two final slow laps – to victory.

Le Mans 1982 alongside Derek Bell

Getty Images

Celebrating Le Mans victory in 1977 with Jürgen Barth and Hurley Haywood

Getty Images

In 1985, in the Spa 1000Kms, Jacky was innocently involved in the accident that cost the life of the young German charger Stefan Bellof. As Ickx’s factory Porsche led Bellof’s Brun car up the hill into Eau Rouge, Bellof tried an impossible overtaking manoeuvre and they collided. Both cars were destroyed: Ickx escaped with light injuries, but Bellof was trapped in the wreckage for 20 minutes, and died shortly after. Jacky was deeply upset: “There are some things you never forget. Although you are completely innocent, you are still part of it, you cannot stop saying to yourself, ‘If, if’. He was a charming boy, very promising, a rising star. Ken Tyrrell was promoting him, like he promoted me 20 years before. My decision to stop racing came naturally after that. If you are realistic you allow these things to push you towards a decision.” He scored his final Porsche victory, sharing a 962C with Mass in the Selangor 800Kms in Malaysia. Then, just before his 41st birthday, he retired.

But he remained a racer. He’d been introduced to the Paris-Dakar desert race by the French actor Claude Brasseur in 1981, campaigning a Citroën CX until they crashed out, and he was entranced by the magnitude and challenge of the event. The next year he and Brasseur finished fifth in a Mercedes, and at the third attempt they won. He got Porsche interested and finished second for them in ’86, and also did it for Lada, Peugeot and Citroën. Then he became involved in the organisation of the event, which due to unrest in Africa has moved to South America in recent years.

“If you ask me what is the most satisfying competition of my life, it isn’t F1, it isn’t Le Mans, it’s the Paris-Dakar. It’s the hardest, most complex race in the world. Flat out for nine hours at a stretch, 130mph on sand. And the sand is unpredictable, like the sea: you can’t trust it to remain the same, because suddenly it will be different. A desert is a place where nobody lives. Nobody. If something goes wrong, you have to find a solution by yourself, out there in the silence. If you think you are important, out there, alone, you realise you are not. And in discovering the event, I discovered Africa. I saw different peoples, a different part of the planet.” For Jacky it was the start of a love affair with the continent that continues to this day.

Jacky’s daughter Vanina, now 36, has been racing for 15 seasons, and at Le Mans this year Jacky watched her finish a fine seventh, second petrol-powered car home, in the Kronos Lola-Aston. “I am proud of her. She is very brave, and drives a big fast car really well.” They have done the Paris-Dakar together: in 2000 their Toyota finished 18th. “It was fantastic to do that event, father and daughter. After that you really know each other. But she navigated; I did the driving. I am not that brave…

“The most satisfying contest for me isn’t F1, or Le Mans, it’s the Paris-Darkar”

With the Grands Prix, all the endurance racing, the testing, and then the desert races too, spanning 32 years I have probably done more racing miles than almost anybody else. And I only had two bad accidents, at Jarama and Watkins Glen. I have been so fortunate. Now that I have grown out of my monorail vision of the world, what interests me is people, the human race. Khadja and I plan to spend more and more time in Mali, where we are having a house built on the Niger River, miles from anywhere. The local builders are wonderful, they work from dawn till dusk, and the workmanship is perfect. Not like on a racing car, nothing is straight, nothing is square, but everything is perfect.

“The article you are writing, I want it to be an expression of my thanks to all the people who helped me in my racing, who shared it with me. Ten years with Porsche, five years with Ferrari, all fantastic people. The father figures: Enzo Ferrari, Jack Brabham, John Wyer, Carl Haas, and of course Ken. And the people who worked with them, who were almost more important: David Yorke and John Horsman at JW, Ron Tauranac at Brabham, Peter Warr at Lotus, and all the people in the chain whose names I never knew. Even the spectators: I do not think they are always well-treated. They should not be like lemons, squeezed for their money to the last drop. Their hearts beat with the passion of racing, and without spectators there would have been no racing for me to do.

“It’s all the other people in your life who help build your story. If you have been as fortunate as me, you cannot say Me, Myself, I.”