Racing Snakes: The Cobra That Captivated the World

1963 Le Mans Cobra For the Cobra’s Le Mans debut, the works AC roadster was one of two 289s given an extended hardtop in an attempt to persuade the air of…

Safe to say that our continental correspondent, Denis Jenkinson, wasn’t all that impressed with the 1970 Le Mans 24 Hours, but little did he know at the time that this race would be looked back upon as the moment of ascention for one of the all-time great racing cars. Porsche’s 917 had already been around for a year by the start of this race, but some catastrophic failings from its first Le Mans outing in 1969 – the cars were superior in terms of pace, but a combination of gearbox issues, oil leaks and terrible accidents meant none of the three entered made it to the finish – forced Porsche back to the drawing board for 1970.

The 917 was notorious during its early life for its rather wayward handling, caused mostly by lift of the nose at speed, due to an aerodynamic imbalance. After some testing with British team boss John Wyer, this was cured by the introduction of two new rear bodywork configurations. The 917K, which featured a completely remodelled rear deck called the kurzheck (German for short-tail). Porsche also hedged its bets by running some 917s in LH (or langheck, for long-tail) spec. In total, there would be nine 917s on the grid for this race – some running 4.5-litre engines, other upgraded to five litres – three times as many as the previous year. But even then, Porsche wasn’t guaranteed the glory. Ferrari provided the sternest opposition, bringing 11 of its new 512 sports-racers to the field. This race would be a head-to-head thrash between the two giants, even if history records that it actually went down as a rather damp squib.

Rather, it was a drenched squib, as heavy and persistent rain led to it being one of the wettest Le Mans races ever. The conditions were so treacherous that by the finish, only seven of the 51 starters were classified.

Jenks’ first issue with this race, and one that he voiced loudly in his Motor Sport report, was the ACO’s decision to abolish the traditional running start. Due to a spate of accidents across the previous two years – including 917 privateer John Woolfe being killed in a 1969 crash shortly after the start – the ACO abolished the traditional sprint across the track, instead demanding drivers start the race in their cars, firmly buckled up.

This riled Jenks, who claimed “Le Mans just fell over and died for me. All question of running across the road had been abandoned and it was said that cars would still be lined up in echelon, with the drivers buckled in and the start signalled by lights mounted opposite the pits. When race day arrived, there were no lights, but four or five marshals standing on the bank opposite the pits, spread out along the line of 51 cars. At 4pm Dr Ferry Porsche raised and lowered the French flag and the cars took their cue from him and drove off. Compared to the traditional Le Mans start, which builds up to a climax, the 1970 start was the dullest thing imaginable (but it was safe and clinical, hurrah..!). the Le Mans start was something almost sacred to motor racing. Lying back, strapped into low-built coupés, very few drivers actually saw the flag. The public were completely deceived, for they pay large sums of money to stand in the area in front of the start and to see the drivers prepare for the traditional run across the road. This time very few drivers could be seen, they sidled into the cars from the midst of groups of mechanics, team managers, helpers and well-wishers. When they all drove off at 4pm, without any atmosphere or excitement whatsoever, the reaction was to wonder where they were all going. As I said, Le Mans 1970 fell flat on its face at 4pm on Saturday, June 13th.”

Never one to mince his words, this was very much before the days of stringent safety. Jenks did, however, brave the dreadful weather to record the moment Porsche made a piece of Le Mans history. His report follows.

After 24 hours in largely woeful conditions, the Salzburg-entered 917K of Richard Attwood and Hans Herrmann finally secured a historic victory for the brand

Photography Getty Images. Taken from Motor Sport, July 1970

After all the 51 cars had gone and one was convinced that the 24-hour race really had begun, there was the thought that it must get better, even though the weather was cold and grey, for the first 13 cars in the line-up had been big Group 5 sports cars, most of them 5-litres, the first 3-litre prototype being the Matra 650 Spyder of Brabham, which he was sharing with Cevert. With 5-litre Porsche 917 coupés driven by Elford (Ahrens co-driver), Siffert (Redman co-driver), Rodríguez (Kinnunen co-driver), and 4.5-litre Porsche 917 coupés driven by Hobbs (Hailwood co-driver), Van Lennep (Piper co-driver), Attwood (Herrmann co-driver), and Larrousse (Kauhsen co-driver) in concerted works-supported opposition against eleven 512S Ferraris, a homeric battle was assured.

There were four factory Ferraris, Ickx (Schetty), Vaccarella (Giunti), Bell (Peterson) and Merzario (Regazzoni), two Scuderia Filipinetti cars, Muller (Parkes) and Bonnier (Wissell) and the Italian-owned one Manfredini/Moretti under the Filipinetti banner for this race. Others were in the hands of Juncadella (Fernandez), Kelleners (Loos), de Fierland (Walker), and Posey (Bucknam), and much was expected in the opening stages of the race. It was not to be, Elford and Siffert ran away from everyone, none of the Ferraris ever looked like being a challenge and the whole thing set out to line up to the proper title of the race, the Grand Prix of Endurance. On the third lap the leaders started lapping the slower Porsche 911 coupés, and the complete absence of Renault-Alpines was very noticeable, Renault having pulled out of racing completely.

The crisp-sounding Matra team, of Brabham/Cevert in a 650, Jabouille/Depaillier in a similar car and Pescarolo/Beltoise in the latest monocoque Type 660 were not in the running, nor were the four Alfa Romeo 33-3 “Spyders” of Stommelen/‘Galli’, Courage/de Adamich, Hezemans/Gregory and Zeccoli/Facetti, and none of the private Porsche 908 Prototype 3-litres were really in the picture. The 5-litre Production Sports Cars, forced unwillingly into being by the hasty decisions of the FIA two years ago, were dominating the scene, and the 3-litre Prototypes that were supposed to have benefited from the change, were completely overshadowed.

David Hobbs/Mike Hailwood’s Porsche 917K took an early lead over the Ferraris, which never looked like a credible threat

The race had barely been going for 30 minutes when the rain began and what had started as a not very exciting race now became positively dreary. Already the Vaccarella Ferrari had gone out with a broken connecting rod, and Pescarolo in the new Matra was having trouble with the front cowling coming loose. The big cars were running for less than one hour before having to stop for fuel and Elford was timed at 331kph down the Mulsanne straight (205mph). It all looked as if it was going to be a 5-litre Porsche walkover, but it was not to be, Rodríguez had his engine blow up, the drive to the cooling fan failing, Siffert retired at the pits in the biggest cloud of smoke imaginable and oil pouring out of the exhaust pipes, and Elford’s car also broke its engine in a disastrous way.

The rain was unbelievable at times and cars were spinning and crashing in all directions, the 62 kilometres of steel guard-rail erected round the circuit keeping all the spinning cars on the track but causing accidents to those following. Parkes crashed his Filipinetti car into cars already crashed but still on the track and Hailwood crashed the 4.5-litre Gulf-Porsche for the same reason, stuffing its nose into the already crashed Alfa Romeo of Facetti, and Hedges crumpled the front of the open Healey-Repco V8 for the same reason. The impressive thing in all these accidents was that no one got hurt, though many cars were demolished, Wissell being hit up the back by a works Ferrari while he was going slowly due to oil on his windscreen thrown back from the Larrousse/Kauhsen 917 Porsche.

The last works Ferrari went out when Ickx crashed at the Ford chicane just before the pits, unfortunately killing a marshal, and all the Matras disappeared from the race quite early on due to “abnormal wear of the piston rings,” as it was stated officially. One observer at a Matra pit-stop said that oil seemed to be coming out of everywhere. After setting in motion a gigantic operation to win Le Mans the Matra effort died away like a damp squib. A lot of cars had spread oil around the track, due to leaks, engine breakages and so on, and with the rain the circuit became like a skating rink, and during the early hours of the morning terrific thunderstorms broke out, setting everything awash, while lightning split the skies. The efforts of those drivers who stayed on the road were truly remarkable, and anyone who spun or crashed could hardly be blamed. There have been some wet Le Mans races in the past, but this must have been the worst ever.

Before retiring with a broken engine about 8.30am on Sunday morning the Elford/Ahrens 5-litre Porsche lost a lot of time, and the lead of the race, due to bad handling which was thought to be a broken chassis at the front, but eventually turned out to be a deflating rear tyre! The Healey-Repco V8 had broken the dogs on fourth in its Hewland gearbox. It was dismantled at the pits and a new one fitted, and the Ecurie Francorchamp Ferrari 512S spent a lot of time at the pits with a faulty fuel pump and then a leaking petrol pipe. The NART Ferrari 512S was not running on 12 cylinders, but was still going strong, and during the rain in the early hours the leading 917 Porsche of Attwood/Herrmann and that of Larrousse/Kauhsen were misfiring badly with water getting into the air intakes.

The last Alfa Romeo to be running was that of Courage/de Adamich, but it sounded awfully rough and by midday on Sunday the engine had succumbed. Previously it had run out of petrol and been pushed to its pit by mechanics and there was talk of exclusion, but it excluded itself with a mechanical disaster. The Alfa Romeo of ‘Galli’/Stommelen had been disqualified for being push-started. Of the 51 starters only 19 were running at midday on Sunday, and many of those were very sick, but the red 917 Porsche with white stripes of Attwood/Herrmann was running well, this being a short-tailed car, the long-tailed 917 of Larrousse/Kauhsen, with its vulgar paint scheme of purple with green decorations thought up by the Porsche styling department was second and the 908 Spyder of Lins/Marko was third.

The Porsche works team, note the JWA truck on the left

Due to the appalling conditions during the night the average speed was low and many cars were behind the minimum distance schedule, and when a major cloudburst flooded the pit area the cars were reduced to 50mph or less. A lone Porsche 914/6 had run like a train and outpaced all the 911 coupés, and the privately entered 908 Spyder 3-litre was in command of the Handicap event, or Index of Performance.

The film company of Steve McQueen had entered his 908 Porsche as a serious entry, driven by Linge/Williams and they had unobtrusively been filming things as they raced, with cameras mounted fore and aft, built into the car. A long delay early in the race when the starter failed put them out of the running and stops for camera loading and suchlike put them too far back to be classified, but nevertheless they were still running at the end of the 24 hours.

As Sunday afternoon turned out bright a vast crowd stood patiently drying in the sun, waiting for the finish, which is as traditional as the start. Each survivor of the gruelling 24 hours crosses the finish line, and this year it really was gruelling and only the fittest survived The co-driver normally climbs on the car together with mechanics and pit staff and the cars stop at the top of the pit straight, where they are turned round and sent back down in front of the 20,000 to 30,000 spectators opposite the pits, to say nothing of the 10,000 all over the pits. From the first car to the last car, the crowd applaud and all those involved soak up the joyous feeling of having achieved something, for to finish at Le Mans is always noteworthy, no matter in what position you finish.

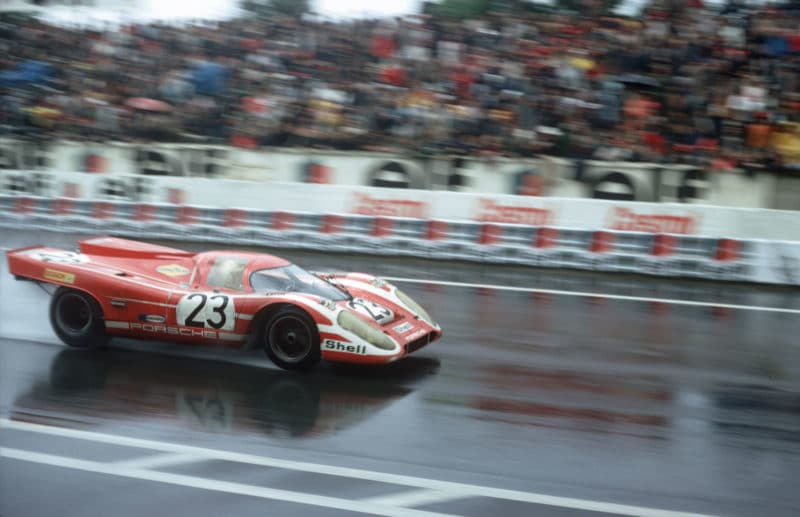

RodrÍguez/Kinnunen’s 917K passes the packed spectator area. Already displeased at the start, the fans must have been wondering what was going on when cars began to drop like flies

The police try in vain to control the crowds who surge on to the track to acclaim the winners, who are up on a platform, with flowers and champagne, and to crowd round the surviving cars, which they have watched from afar for 24 hours. It is chaotic, but it is joyous, it is the real ending to the Le Mans 24 hours.

Last year, when the race was won by a mere 100 yards the chaos got out of hand, such was the excitement and enthusiasm of the public. In consequence a new form of ending was planned, about which the public were informed in the last minutes of the race. As the cars finished their last lap they were impounded in a guarded enclosure and the winners were put in the back of a sand-and-gravel lorry and it set off on a lap of honour. It was actually a lap of dishonour, for the lorry looked like a dustcart setting off to pick up rubbish. There was no public presentation, no sign of the cars, nothing at all, so a very disillusioned public just went home, feeling thoroughly cheated, having been deceived at the start and robbed of all their excitement at the finish.

As local papers put it, the start and finish of the Le Mans 24 hours is a sort of folklore of la Sarthe and the Automobile Club de l’Ouest had robbed the public of it. They likened the farce of taking the winners off in a large lorry to prisoners-of-war in transport, of Louis XVI on his way to the guillotine. They said that the traditional start and finish of the Le Mans race gives a human dimension to a purely mechanical affair, and they felt the spectators had been robbed.

The Elford/Ahrens 917L featured strongly before its engine let go after 18 hours

While it was the first Le Mans victory outright for Porsche it was at some expense, and was not a very joyous one, for the whole race had been like the weather, cold, wet and miserable. They had won by sheer weight of numbers, and also won the Index of Performance, the fuel-consumption/weight handicap, the Sports-Car category, the Prototype category and the GT category. In fact, they won all that it was possible to win.

Every year there is someone who deserves the bad luck prize and this year it must have gone to Hedges and Enever in the Healey Repco V8, for after two slight accidents, rebuilding the gearbox and having starting troubles, it was going well and all set to finish when the ignition died completely with barely 15 minutes left to complete the 24 hours. It was on the Mulsanne straight and had to be abandoned, the single Repco V8 engine having not missed a beat all the time until this sudden instant cessation and loss of electrics.

Podium celebrations, but in a truck… another one of Jenks’ 1970 bugbears

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bx7saF780Gk