From the film archive...

TAKEN FROM MOTOR SPORT JANUARY 1958 A popular winter motor-racing entertainment is the BRSCC Festival of Speed and Sport, which took place last year on November 22nd. It is astonishing, even…

Murphy/Daily Express/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

A couple of evenings before this year’s Long Beach Grand Prix the phone rang in the Rolling Hills, California home of Ed and Sally Swart. On the other end of the line was Dario Franchitti, inviting the couple to be his guests at the race.

There is no doubt that Franchitti, who was to win that weekend, has a sense of heritage. At the victor’s press conference following the 2007 Indianapolis 500 the emphasis was on the fact that just two Scots had come first at the Brickyard; Dario was in august company, the other being the man who many argue to have been the greatest racing driver of all time, Jim Clark.

At the Road Racing Drivers’ Club dinner — held in honour of Dan Gurney — that took place the night prior to his phone call, Franchitti had made a point of seeking out Sally Swart, whom he had not seen since the Jim Clark Reunion in Scotland in 1993. The reason he was so eager to remake her acquaintance was that between 1963 and ’66, among the highlight years of Clark’s career, Sally Stokes as she was then was the twice World Champion’s steady girlfriend.

Jim Clark with girlfriend Sally attending the premiere of the Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor film Cleopatra at the Dominion Cinema, London in 1963. Whether Clark enjoyed the epic is not known but he was certainly a Sound of Music fan

Daily Express/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

The London Motor Show in 1966, Stand 173. Sally is in the chequered dress modelling a Crayford converted soft-top Cortina. Beside Sally is racing driver Anita Taylor, sister of Formula 1 driver Trevor Taylor. Anita was a regular in saloon cars in the mid-1960s – a time in which Clark saw much success

Staff/Mirrorpix/Getty Images

Clark at the family home, Edington Mains Farm near Chirnside in Berwickshire, 1963. The Clarks moved here when Jim was six years old and he would later run the 1250-acre farm. It is here that he first took the wheel of a tractor, aged 10

John Pratt/Keystone Features/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

as well as flying around racing circuits, Clark was also a keen pilot. This was his own aircraft that he used to travel across Europe for races

Robert Riger/Getty Images

In the late 1950s Sally had been part of a circle who founded the Midland Racing Partnership — with drivers such as John Rhodes, Richard Attwood and David Hobbs. On a visit to Mallory Park, the group had been impressed “that five of the seven races were won by this obscure farmer from Scotland who jumped into every car you could imagine, including a Lister-Jaguar”.

Sally, a young photographic model with a passion for horses and theology, moved to London in 1961, maintaining her friends in motor sport who by now included John and Gunilla Whitmore. In the summer of ’63, having been sunbathing in Hyde Park, she walked to the Whitmore’s flat in Balfour Place, just off Park Lane, to keep a lunch date with Gunilla. “I think I was looking rather scruffy. To my horror, Jimmy walked in.” By now the “obscure farmer” was on his way to his first World Championship and, although they had not met before, Sally was well aware of who he was. “Gunilla said she had an appointment and rushed off, leaving us alone. I should have known that this had been plotted, but I was so naive it was years before I discovered it had been a set-up.” The result was an invitation to the opening night of the film Cleopatra. “We had a good time travelling to the theatre on the tube, all in evening dresses and black tie, with a few friends including Stirling and Elaine Moss.

“Quite soon after I went to Brands Hatch with Jimmy.” (Sally remembers he was always “Jim” to his family but usually “Jimmy” to his friends.) Clark was driving a Ford Galaxie with a bench seat. “He slipped on the seat going through Paddock Bend. He said he was all over the place trying to hang on to the steering wheel.” Sally recalls another saloon car memory from the following year. The area behind the pits at Brands was then just a grass field. Clark got into trouble exiting Druids and ended up reversing at speed across the grass and right into the pits. “If you can’t win, at least be spectacular,” he told Sally.

The quickest way to get around London in 1963 – by bus. Note the conductor, a concept younger readers will not be familiar with

Bentley Archive/Popperfoto via Getty Images/Getty Images)

Soon she had been initiated into the Women’s Motor Racing Associates’ Club and the Dog House Club, and started carrying out timing duties for Clark. “Colin [Chapman, founder of Lotus] gave me a lap chart and a stopwatch and set me to work. It helped distract me from worrying about Jimmy. At first I had just a notebook; a proper timing sheet came later.” The pits were a completely different world from today. At one race Sally was sporting the new fashion of stick-on fingernails. “During frantic lap charting, one of these flipped off. I dashed under the counter to retrieve it much to the amusement of the Lotus mechanics. At this point Colin came in, observing, ‘Hello, hello… she loses her nail and the whole of the Lotus pit shuts down.’”

In 1965 Clark notified Team Lotus competitions manager Andrew Ferguson that Sally would accompany him to all of his races. That meant not only the Grands Prix but also Formula 2 events and the Indianapolis 500, which the Scot was to win at last. The year before, Clark had come back laughing from the Speedway. He had asked for a boiled egg at the Holiday Inn but was told that he couldn’t have one because the egg-boiling machine had broken down. “He was amused and frustrated by the fact that they could not just put an egg into boiling water and time it.”

dinner with Colin Chapman in 1966. This was a lean year compared to the previous one, with just a single F1 world championship win coming at Watkins Glen

Bentley Archive/Popperfoto via Getty Images/Getty Images)

Sally did not attend the whole month of May. “Jimmy used to say that it was horrendous, quite boring, but very necessary because he had to set up for the 500.” She recalls Clark telling her how much he liked the actual race at Indy, “because when I am in the lead, I have dollar signs flashing before my eyes”. Being paid for leading a lap was new to him and, as Sally states with an infectious chuckle, “being a Scot he liked to line his pockets”. Other than this, they never spoke about money. However, she does recall one rainy day at Snetterton shortly after he had won at Indy. Walter Hayes, at that stage Ford UK’s PR chief, was “wringing his hands and saying, ‘It’s absolutely ridiculous how little we are paying this guy’. I merely replied, ‘Oh really!’”

On the day of the 500 Sally and Colin Chapman’s wife, Hazel, joined Bobby Johns’ family in the grandstands (Johns had driven the second factory Lotus the previous year). Women were not allowed in the pits or garages then. Lotus chief mechanic Dave Lazenby reckoned that Sally and Hazel ought to be “like the rest of the girls” and hang by their fingernails on the fencing round Victory Lane.

“When the cars came down the straightaway for the first time, Bobby’s sister started crying and I almost joined her,” says Sally. “I had never thought to fear like that before. The Indycars had big, fat fuel fillers which we were not used to — remember we didn’t have fuel stops in Formula 1 then. Colin being Colin redesigned the fuel feed from the Esso tank to improve fuel flow. To disguise this he wrapped the fuel hose in tiger stripes. Officials challenged him but he replied with Esso’s advertising slogan of the time, ‘I’ve put a tiger in my tank,’ and he got away with it.”

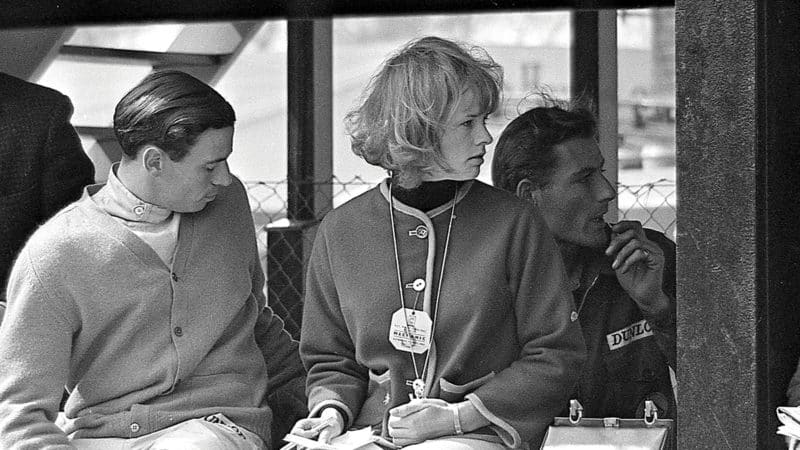

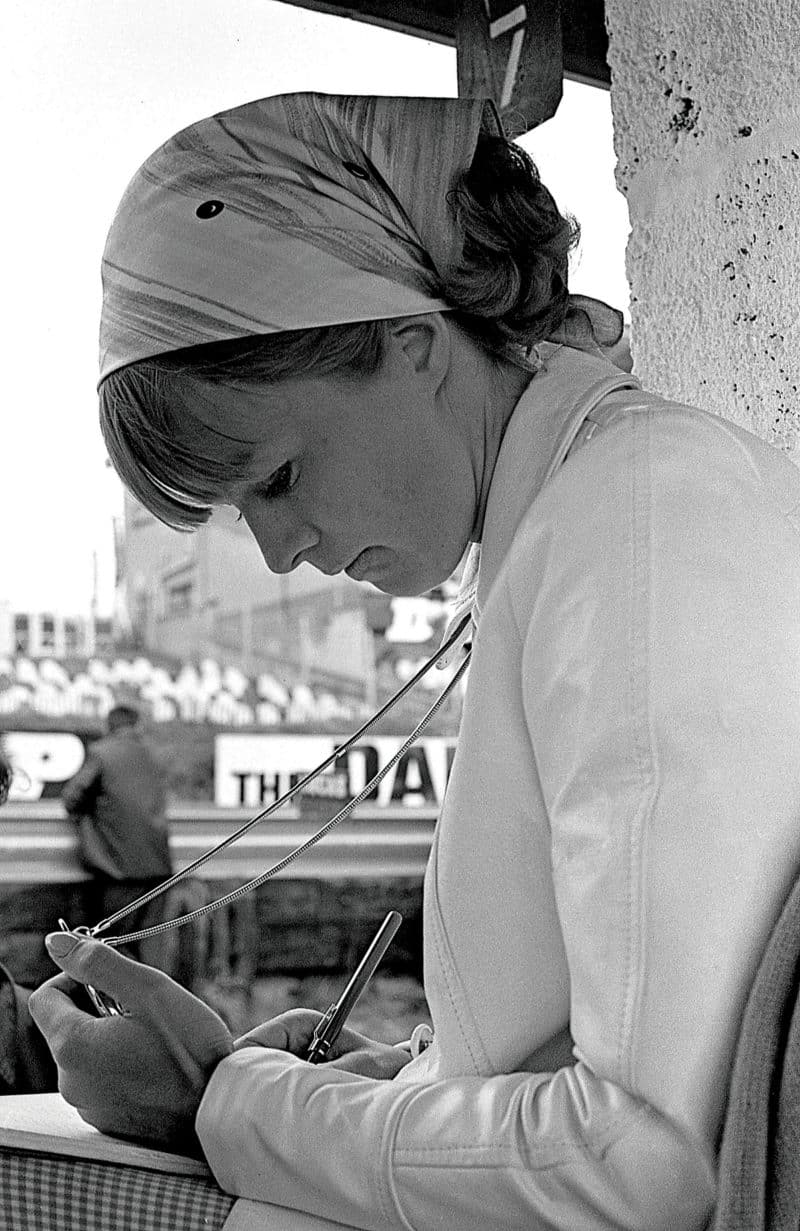

Sally keeping notes at Silverstone. Clark’s girlfriend carried out timing duties, which diverted her attention from the dangers of F1

Sally can’t remember how she and Hazel made their way across the track after the race, but they were eventually allowed into Victory Lane. At the subsequent post-race dinner and festivities, Sally and Jimmy could tell that there was a “little gap in the enthusiasm”. Sally has her suspicions: “I didn’t know the half of what had gone on but they had almost tried to prevent Jimmy from winning. Jim had known that and already warned me, ‘They’re not too enthusiastic that I’m here.’ That was rather sad; it dampened the activities for us. However, I do know that he was welcomed in later years with more enthusiasm.” Even today, Sally believes that Parnelli Jones — now a friend and very close neighbour of the Swarts — should have been black-flagged by the USAC officials for shedding oil in 1963 and that Clark should have been given the win that year.

“After the race, I had my picture taken with Mario [Andretti], the Rookie of the Year and such a nice young man. Jimmy, I know, was very impressed with Mario’s talent. He thought him very promising.”

The next month Sally, Clark and Mike Spence flew in Chapman’s plane from Luton to the French Grand Prix at Clermont-Ferrand. “There seemed to be quite a bit of activity at the airport. We had forgotten that the Paris Air Show was on. The French Government had flown Yuri Gagarin [the first man to travel in space] down from Le Bourget to show off a new plane. There was a civic reception for him. We crept in at the back but it was known from our flight plan who we were. It was only a few weeks after Jimmy’s Indy victory and we were invited into the party and plied with champagne.

“We saw somebody whisper in Gagarin’s car and he jumped up. It appeared he knew exactly who Jimmy was and that he had just won at Indy. He gave him a hug and a kiss — very unusual in those days — and I shook his hand. He seemed thrilled to meet Jimmy.”

There was more to come that day. To Chapman’s annoyance, Ferguson had booked the group into “some fancy hotel up the mountain” and not their usual abode for Clermont-Ferrand. Sally recalls that the Lotus boss was “driving way too fast” in their hired Peugeot. (“Colin was a wild driver, Jimmy wasn’t. He just drove normally in town but up in Scotland he used to accelerate a bit and enjoy himself.”) Sally was sitting in the middle of the front bench seat with Clark at her side and Spence in the back.

Farmer Jim in 1965 – the year he was crowned Formula 1 world champion

Robert Riger/Getty Images

“Colin launched into a right-hand bend, didn’t make it and ended up in a shallow ditch. I went through the windscreen and Colin broke his thumb on the steering wheel. Jimmy climbed out of the door, sat down on the grass and promptly fainted. I pushed his head between his knees. He came to, complaining that I was bleeding all over his new suit.” The men wanted to pull the Peugeot out of the ditch and requested Sally to sit at the controls. It was dark and the headlights had gone. Suddenly they saw that the car was on the edge of a cliff and screamed at her to “hit the brakes”.

“We never did find that fancy hotel and instead went back to where we usually stayed. Bleeding, I was hidden from the press, but it was not good for a model to have a scar on her lip. In the middle of the night Colin and I crept out to the hospital and my wound was stitched up. I had my scarf pulled over my face during the race — which Jimmy won.”

A t the end of the 1965 season Clark made his usual trip Down Under for the Tasman Championship. Sally, along with Bette Hill and Helen Stewart, joined their men for the Australian leg of the series. However, during the time of the earlier New Zealand races, Warwick Banks had introduced Sally to one of his fellow saloon car racers, the talented Dutch Abarth driver Ed Swart. She recalls that her relationship with Clark “lightened up” following their return from Australia. As the Scot’s career became increasingly professional and he took tax exile in Paris, so Sally started to spend more time in Swart’s company. She and Clark were to remain firm friends, however, even after her marriage to the Dutchman.

June 1966, from left, Clark, Bette Hill, Graham Hill, the Hills’ daughter Brigitte and Stirling Moss

Bentley Archive/Popperfoto via Getty Images/Getty Images

“Jimmy’s driving skill was a God-given talent. Heavily talented artists tend not to be well-rounded and I think he was probably like that. I realised he wasn’t going to change. He also didn’t want to get married until he stopped racing and I realised he was not about to change that. Why should he?

“His mastery in a car made him a true artist. When he got out of one he almost became a different person. I once asked him how he made up his mind to turn the first corner and he laughed, ‘That’s automatic’. But he did take time to make decisions. He would have trouble deciding where to eat. It became a bit of a joke, but good for me as we usually ended up dining at my favourite restaurants. Jimmy was easy-going but quiet and introverted. I liked to think of him as a ‘dour’ Scot although that is probably the wrong word.

“He seemed very aware of what his family would think of his actions and whether his father would approve. I respected that. He always wanted to behave honourably. For example, he didn’t really like having his picture taken with me for fear that the press would misuse it. I had trouble with that as it was hurtful to me, but I tried to understand his reasoning.

“He liked to keep things low-key and didn’t make a fuss about himself. He was uneasy giving interviews and had great trouble in public speaking.” Prior to a dinner, Clark would ask Sally if she had a joke he could tell. She still has the copy of a BARC dinner programme that Clark annotated with reminders for his speech. Over time, Sally noticed an improvement in this: “I saw him become more relaxed.”

Normally Clark wouldn’t show any form of emotion. It was probably a family trait. Even at his funeral one of its members told Sally that she must not cry. “You had to be very ‘cool’ in his company. I would have never dreamt of rushing up and giving him a kiss after he had won a race. I don’t think he would have liked that, although I never discussed it with him.”

Sally does recall, however, that his favourite film was The Sound of Music. “I didn’t think somebody like him would appreciate a film like that. It showed another side to his character; he did have a softer side. We even shed a tear when the nuns were singing about Maria!

Sally accompanied Clark to most of his races in 1965. She knew better than to rush up and kiss her boyfriend after a race

“He was a very good letter writer and that was something I really appreciated — one was written on the back of a South African Airlines menu ‘somewhere over Mauritius’, he said. He learnt that from his family. I still get great letters from his sister Betty, while his father was still writing to me when he was in his eighties.” Sally had started travelling to Scotland to meet Clark’s family early in their relationship. She has remained close friends with many of its members. Betty is godmother to the Swarts’ daughter Sharon and has often visited the couple. Even after Clark’s death Sally took her children to visit his parents every year.

For many of Jim Clark’s fans, the first they heard of his death was over the Tannoy at the 1968 BOAC 500. Sally is acutely aware that he should have been at Brands Hatch himself that day, driving a Ford F3L. Over a lunch, entrant Alan Mann had even thanked Chapman for letting Clark drive the endurance car, only to find later that the Lotus boss had then entered him for an F2 race at Hockenheim. Sally — who had been told by Clark over the phone that he would be in Germany — was at Zandvoort as husband Ed was entered in his first race of the season at the wheel of an Abarth sports car.

Sally was on her own, sitting in their car in the pits and thinking that she ought to start work on her timekeeping duties when she heard a newsflash on the radio. Her knowledge of the Dutch language was, at that stage, in its infancy. Clark’s name was mentioned coupled with the word overleden. Worried, she rushed to her father-in-law who went white and confirmed it meant Clark had been killed. The next day she was on a plane for Scotland.

Shortly after Ed and Sally moved to California in 1980 they attended a beach party where one of the guests told them that the day after Clark’s death he had been driving along the 405 freeway. The announcer on the radio suggested that all those listening who were mourning the death of “the great racing driver Jim Clark” should turn on their headlights. He said the whole of the 405 lit up. “I told Mum and Dad Clark about that and they were deeply moved. I only have golden memories of Jimmy in every shape and form. I really treasure the memories of our times together and consider it a privilege to have known him.”