Sports Cars & Saloons: Crimond

It was 1956 when Jim Clark was coaxed into making his racing debut at Crimond. David Finlay revisited the site with Ian Scott Watson, the man who did the coaxing...

Standing on a piece of dull Aberdeenshire countryside, shivering against the wind as it blasts off the North Sea, you might not at first realise that there was anything of particular motor sport significance going on, or that the ghost of one of the most remarkable careers in racing history was whispering around you.

More fool you, then. This is Crimond airfield, just beside the village of Crimond and about halfway between Fraserburgh and Peterhead. It’s on what used to be known as the ice cream road, in the days when you bought an ice cream in one town and bet your friends that it wouldn’t have started melting by the time you drove into the other. It was a feat requiring a very high average speed, which is why the Fraserburgh to Peterhead road is now the most Gatso speed camera-intensive in Scotland.

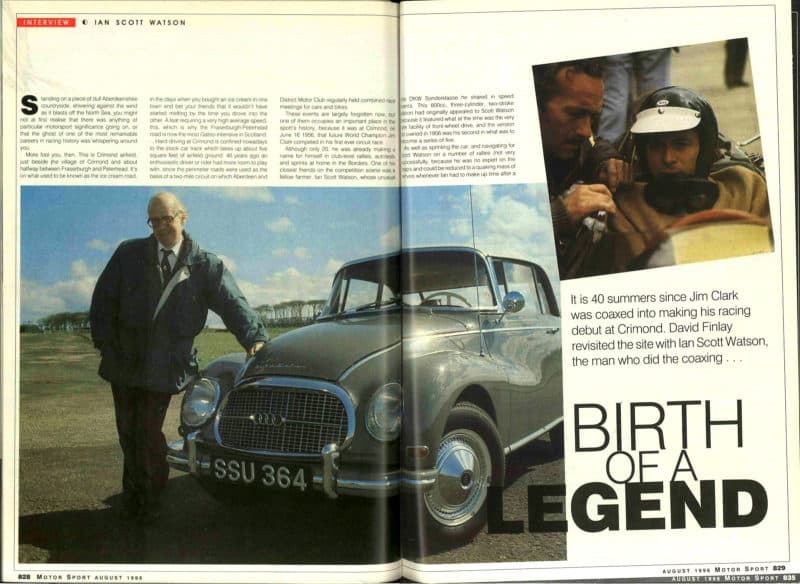

The 1996 Motor Sport article with Scott Watson and an Auto-Union 1000 – the nearest thing in Britain to the Clark-driven DKW in the mid-1990s

Hard driving at Crimond is confined nowadays to the stock car track which takes up about five square feet of airfield ground. In the mid-1950s an enthusiastic driver or rider had more room to play with, since the perimeter roads were used as the basis of a two-mile circuit on which Aberdeen and District Motor Club regularly held combined race meetings for cars and bikes.

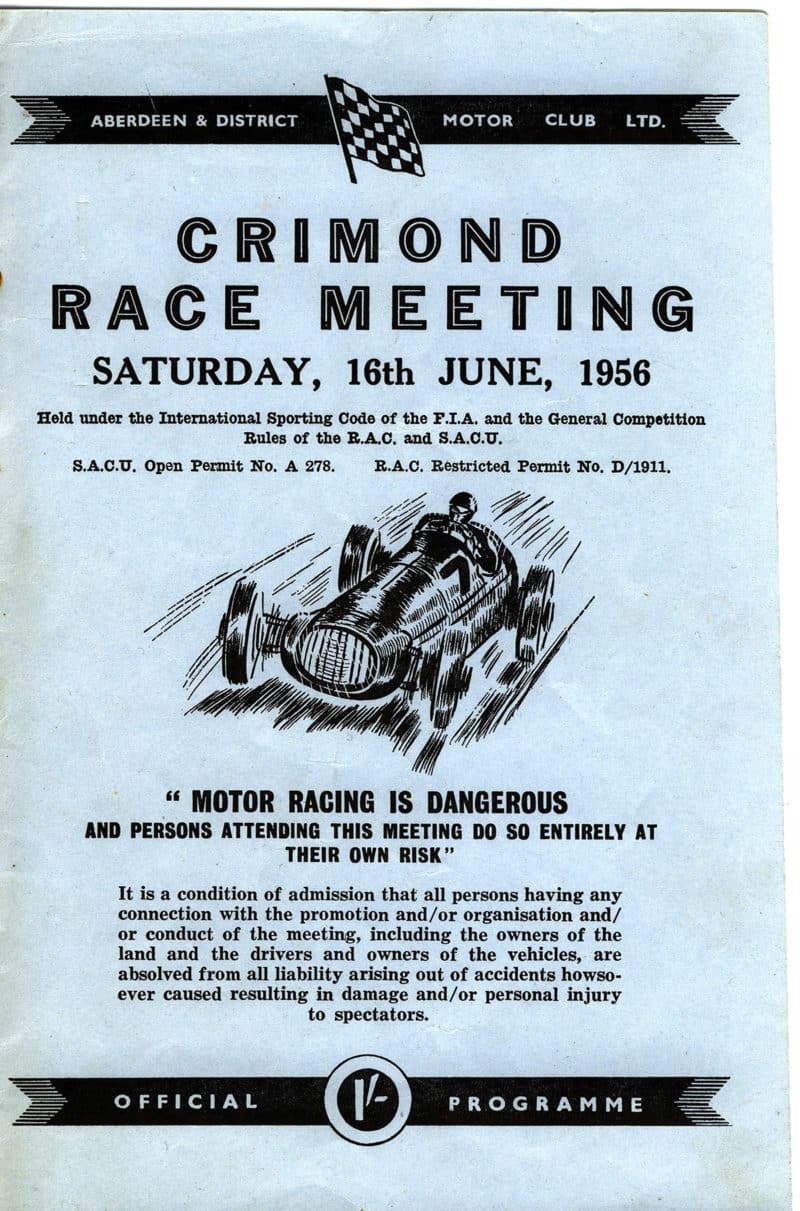

These events are largely forgotten now, but one of them occupies an important place in the sport’s history, because it was at Crimond, on June 16 1956, that future World Champion Jim Clark competed in his first ever circuit race.

Although only 20, he was already making a name for himself in club-level rallies, autotests and sprints at home in the Borders. One of his closest friends on the competition scene was a fellow farmer, Ian Scott Watson, whose unusual DKW Sonderklasse he shared in speed events. This 800cc, three-cylinder, two-stroke saloon had originally appealed to Scott Watson because it featured what at the time was the very rare facility of front-wheel drive, and the version that Ian owned in 1956 was his second in what was to become a series of five.

As well as sprinting the car, and navigating for Scott Watson on a number of rallies (not very successfully, because he was no expert on the maps and could be reduced to a quaking mass of nerves whenever Ian had to make up time after a wrong slot), Clark also prepared the DKW at race meetings. Admittedly this amounted to little more than removing the spare wheel and applying numbers to the doors, but Scott Watson was sufficiently grateful to suggest that he take part in the event at Crimond.

This suggestion came about through a combination of chance and subterfuge. Ian would never have considered it for a meeting at Charterhall, since that was too close to home: Clark’s parents, who hated the idea of their son taking up circuit racing, would have heard about it immediately and made their feelings very clear. And in normal circumstances Crimond was too far away, about four hours’ drive to the north, to think about visiting.

Clark in the ‘Deek’ in 1956, where a flat cap was seen as good enough head protection. The future world champion was 3sec a lap faster than the car’s owner

The abnormal circumstance regarding Crimond, though, was that the secretary of the meetings held there was one Noreen Garvie, a cousin of Clark’s, who was keen to see her relative and his friend at one of her events. Ian agreed to enter the handicap race, and since there was no chance – how could there be? – of Clark’s parents finding out, he quietly persuaded Jim to go out in the sports car event.

As far as results were concerned it wasn’t an auspicious day for either of them. Clark, up against Lotus Elevens and the like in a heavy, underpowered saloon car, finished well down. Scott Watson, who was rather shaken to see that in practice Clark was nearly three seconds quicker than him within five laps of leaving the pits, found that the organisers had also taken this fact on board and promptly handicapped him to smithereens.

June 16 didn’t get much better after that, either. It turned out that Clark wasn’t the only relation Noreen Garvie had attracted to Crimond. A number of other cousins were there, too, and of course they were very excited about seeing one of their clan out on the circuit. News of Clark’s exploits got back to the family home faster than the DKW did, and a reception committee was waiting for the travellers on their return. “In perfect fairness it really was a very good-natured grilling,” Ian said years later, “but I do remember taking the blame and apologising profusely.”

Just three years later, Clark was racing at Le Mans in a Lotus Elite

Not much of a day, then, but look what it led to. ‘Who was the world’s greatest racing driver?’ is a pretty fatuous question, but any attempt to answer it invariably involves mention of Clark’s name. It was the Crimond meeting that started the ball rolling – Clark’s parents could hardly object to his starting racing when he had already done so, which removed the principal obstacle to his early career.

He still needed an opportunity, though, and that was provided by Ian. Clark’s performance in practice was enough to convince him that he needn’t take competition driving too seriously in future, and although he was an enthusiastic racer for several years afterwards his main efforts were concentrated on helping Clark, first by continuing to lend him cars and later by acting as team manager for Jock McBain’s Border Reivers team, which was re-formed in 1958 largely as a way of pushing Clark on to greater things.

And now, with all that in mind, here we are at Crimond, celebrating in a small way that immensely significant race meeting of so many summers ago. There are five of us present, trying to work out the old circuit layout through a maze of radio masts and wishing the wind would die down.

Apart from myself and a photographer, our party includes David Ross, motoring correspondent of the Aberdeen Evening Express, who has been very helpful in providing archive material, and his friend David Simon. These two visited Crimond as schoolboys, but there is an extra significance to Simon’s presence, since he is something of an authority on the DKW Sonderklasse and has very kindly brought his own version along.

Well, not exactly. In fact his car is a 1961 Auto-Union 1000, but apart from a slightly enlarged engine it’s in effect a wide-bodied Sonderklasse with a different badge on the nose. The car Clark and Scott Watson raced at Crimond was the earlier, narrow-bodied model, but Simon reckons there are none of these left in this country, and in any case all Scott Watson’s later Deeks were wide-bodied ones. As a hark back to those days, the Auto-Union is more than good enough, and we’re delighted to have it here.

The closest relative to DKW on the British market is Audi, which has kindly supplied an A4 for the day. There’s a nice tie-in there too, because the A4 is the model with which Audi is doing a good job of trying to win the BTCC, which Clark himself won in 1964, in between his two World Championships.

With due respect to those mentioned so far, the most important of the five people here is without doubt Ian Scott Watson himself. He has taken time out from his occupation of designing timber frame houses to make this trip, and at first he finds it difficult to relate this featureless ground to the old race circuit. But one look along the main straight, which rises evocatively beyond the pits before disappearing over the horizon, and it all comes back.

The race meeting where it all began. The Aberdeenshire track was a four-hour drive from Clark’s Borders home

A ride in the Auto-Union has a similar effect. This is my first time in such a car, and the smooth, high-pitched scream of the engine, like a sewing machine, is a new and amazing experience. To Ian it recalls the days when he would wind a similar engine beyond what should have been its bursting point down the long straights of Crimond and Charterhall, before hurling it into the next corner and revelling in the fact that the damn thing simply refused to let go.

It’s a pleasant day out, all the more so for being low-key and informal. Any magic there might be is hidden in the background for now, especially when the immobiliser on the car Ross is testing decides to stay on permanently, and we guiltily leave him there waiting for the rescue services.

Ian takes the wheel for part of the drive south, and he is soon flinging the A4 over rally roads he remembers from the 1950s. “A worthy successor to the Deek,” he says cheerfully when asked about the Audi, “but not as much fun!”

You’ll gather from this that he is still an enthusiast. He is also one of the most down-to-earth people I know. For that reason it comes as a small shock every time someone refers to him, and it happens a lot, as one of their motor sport heroes. In terms of stature within the sport he has been compared in print to Enzo Ferrari. Sitting with Ian and chatting about classical music, or the current state of Scottish motor sport, or places to eat in the Borders, you just don’t get the feeling of awe that I imagine people across the world must expect there to be. Which is why these chats are so enjoyable.

But when you think about Crimond, and his willingness to let a friend race his road car, and the work he put into helping that friend progress as a driver, and the dominance that friend was later to achieve, the enormity of what Scott Watson did soon becomes apparent. Clark’s career was astonishing. To have stood, decades later, on the track where it started, alongside the man who started it, makes me feel both proud and humble.