Rediscovered: Ferrari’s lost F1 masterpiece

Niki Lauda’s Ferrari 312T Formula 1 car, which won four grands prix in 1975, has emerged after decades hidden from public view. Doug Nye explains its significance and reveals how a revolutionary design reignited an ailing Ferrari in the mid-1970s

Ian Wells

Taken from Motor Sport, August 2020

To Mr Ferrari, the only Formula 1 car that mattered was his current one; retired grand prix cars were redundant. But that’s not how many of us may see it. Old F1 cars, whether they carried great drivers to famous wins or became over-optimistic duds, represent more than simply money. They represent our memories, their provenance connecting us to our past, or even to years and decades before our own lives, to times that exist only in old photos, films, books and magazines. Old F1 cars matter. And the one you see here, pictured in the metal for the first time in 30 years, matters more than most – perhaps most of all.

Ferrari 312T chassis ‘023’ carried Niki Lauda to four of his five grand prix victories in a dominant 1975 campaign in which he took the first of his three World Championship titles, ahead of two more race wins early in 1976. In many ways this is the car upon which Niki Lauda’s legend was built. The story of how this car re-emerged, almost exactly as Lauda left it, right down to the scuffed seat and worn steering wheel, is told later on. Suffice to say this car is arguably the perfect example of an ‘old F1 car’.

Chassis no023 was only ever driven by Lauda and remains in exactly the state the Austrian left it

Ian Wells

The Ferrari 312T also represents the best of the 1970s, a decade that grows ever more radiant the further we travel from it. To many who lived through them, those years were a bleak hangover to the golden optimism of the ’60s – but in F1 terms, they were wonderfully garish, loud and brash to match the clothes, music and wallpapers of the time. To Ferrari and its 70-year unbroken F1 history, the decade represents a glorious reawakening. Mauro Forghieri created a car in which the blunt-speaking, buck-toothed Austrian – initially considered by many to be little more than just another upstart pay-driver – snatched Jackie Stewart’s unclaimed crown as the benchmark racing driver of a new generation.

“Once thought a pay-driver, Lauda snatched Stewart’s benchmark”

From 20 available world drivers’ and constructors’ titles, Ferrari claimed seven in the 1970s, a tally matched only by Lotus. Tyrrell and McLaren shared the rest, three apiece. More than mere statistics, more than the unprecedented constructors’ title hat-trick between 1975-77, the 312T represents the spirit of a blazing age in which Ferrari finally unlocked all its pent-up potential that went largely untapped since the 1950s.

But where did the root of that Ferrari and Forghieri dominance come from? The answer begins in 1974 and the decision by Maranello to end its time and money consuming sports car programme to focus entirely on returning to the fore in F1, beginning with the curiously angular 312B3 flat-12.

The design was developed into a successful machine, but failed to bring Ferrari its first constructors’ title in over 10 years, partly due to the relative inexperience of its lead driver. Of course, the driver was Lauda, and he was paired with the hugely experienced and capable Clay Regazzoni.

Ferrari’s F1 focus, and the completion of its private Fiorano test track, situated just across from the main Formigine Road factory, enabled it to test constantly, and Lauda was always available. He realised his future, and the team’s, depended upon exploiting all advantages. After creating a new F1 car, Ferrari could run extensive tyre testing for Goodyear.

If five differing wing sets were available, then Ferrari would test each pair individually, studied and extended to its potential in great detail. Every minor alteration and change would simply be tested fit to bust until the sun went down and the brief Emilian dusk settled over Fiorano. Since it had this luxury of its private test track, there was never a problem with booking public circuits, while transporting the cars from the factory to test venue meant wheeling them out of the shop door.

Lauda cleverly managed an ailing 312T to hold off Fittipaldi and claim the Monaco ’75 win, Ferrari’s first victory there in 20 years

Getty Images

Once Ferrari had all these assets in place, it was able to tackle F1 more seriously than any rival. In this way, it could compensate for some distinct shortcomings, particularly in chassis engineering, which would occasionally leap out of the bushes and beset the team in coming years, notably once aerodynamics became increasingly sophisticated.

But for three halcyon years, 1975-77, Ferrari was on top of its game. It became the first F1 team in history to put together a hat-trick of three consecutive constructors’ titles – a remarkable feat at the time.

When its 1974 campaign ended in the United States Grand Prix at Watkins Glen – where the drivers’ title was decided between Regazzoni’s Ferrari 312B3-74, Jody Scheckter’s Tyrrell and eventual winner Emerson Fittipaldi’s McLaren M23 – Ferrari took stock.

Its direttore tecnico Mauro Forghieri could reflect upon a year of adequate flat-12 engine reliability, though failures at the Österreichring and Monza proved costly. The 312B3-74 chassis survived without major changes, other than detailed aerodynamic tweaks, but Forghieri felt the basic concept offered more potential.

Lauda at Monza ’75, where he sealed his first title

Getty Images

It was actually on September 27, 1974, before Ferrari set off for that US GP, that the new year’s prototype 312T model was unveiled to the press at Fiorano. Forghieri in effect was following Derek Gardner of Tyrrell and Robin Herd of March’s path in ’72, seeking further concentration of mass within the wheelbase to produce a highly nimble car, which might seem too nervous to the average F1 driver, but which the likes of Ronnie Peterson or Niki Lauda could turn into a formidable weapon.

Where the 1974 car’s suspension coil-spring/damper units had been mounted on each side of the chassis footbox, with a spidery forward tube subframe picking up the leading elements of the lower wishbones, the redesigned 312T tub carried all its major front suspension components on the forward face of its monocoque’s front bulkhead.

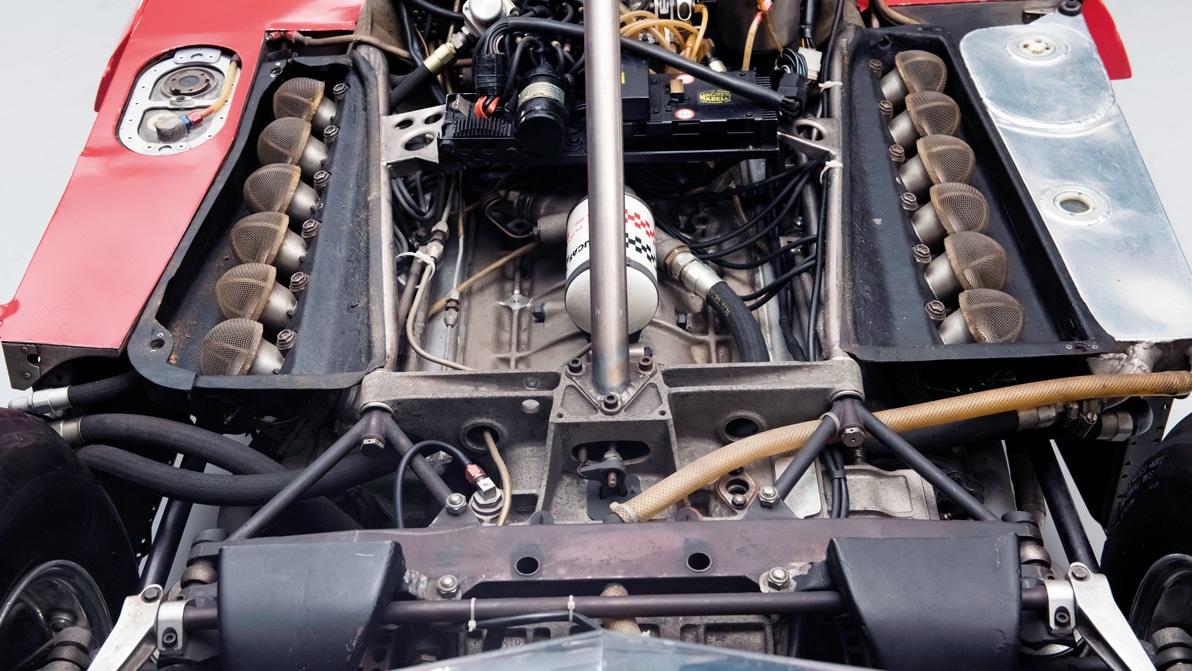

312T ‘023’ is as it was when it raced

RMA/Bob Harmeyer

Long fabricated top rocker arms actuated steeply inclined Koni dampers, with co-axial tapered wire rising-rate coil springs, whose feet were anchored in a cast magnesium tray, fitted to the bulkhead. The monocoque’s front end was considerably narrower than its predecessor, and the tub used Ferrari’s familiar hybrid construction technique in which the stressed-skin structure was reinforced internally with steel strip and angle framing.

Disc brakes were mounted outboard at the front, inboard at the rear. Up front, a system of links and levers actuated an exquisite little anti-roll bar, which was bracketed to the centre of that assembly, and a trailing top link from the upper arm fed back into the tub, passing through an air duct section designed to feed water radiators slung either side, just behind the front wheels. Long side ducts fed air through oil coolers each side ahead of the rear wheels, while beautifully moulded GRP body sections included a sharp-pointed shovel nose, with a full-width airfoil wing. Sidepods served the regulation deformable structures, which overlapped the monocoque sides. The cockpit surround and engine cover-cum-tall airbox were formed in one moulding, smoothing airflow onto the centre-strutted rear wing while curled flip-ups moulded ahead of the rear wheels faired airflow around the broad Goodyear tyres.

Dials could show over 1200rpm and would read Niki’s oil pressure loss in Monaco ’75

RMA/Bob Harmeyer

Rear suspension was by reversed lower wishbones, replacing the original toe-steer restricting parallel-link system in an apparently retrograde move, although it saved weight. Like McLaren, Ferrari felt it could control toe-steer with careful set-up tweaks in assembly.

Compared to the 1974 312B3 model, the wheelbase of this new Ferrari 312T was increased nominally to 99.1in, while front track was 59.4in and rear track 60.2in.

The most significant technical innovation was the new transverse gearbox, which mated conventionally to the rear of the flat-12 engine, but with most of its mass concentrated ahead of the axle line, within the wheelbase, thanks to its gearwheel shafts being aligned laterally instead of longitudinally, as was the norm. Gearbox input turned through 90-degrees by bevel gears to enable the gearbox shafts to be arranged laterally, final-drive then being via spur gears. Ingegner Franco Rocchi’s hugely experienced engine team had worked hard on the flat-12 engine, and in its latest form, 500bhp at 12,200rpm was being claimed.

In testing at Fiorano, Lauda found the new car far more demanding to drive than the B3-74, as predicted, but equally, its ultimate limits seemed much higher, and with practice, he was able to drive closer to those higher limits for longer. The maturing driver was soon lapping Fiorano at 1min 13sec, compared to Art Merzario’s best of 1min 14.2sec set in the original Forghieri B3 car 15 months before.

“In testing at Fiorano, Lauda found the new car far more demanding”

At Vallelunga, further testing meant Lauda lapped in 1min 7.5sec, a second inside the best B3-74 testing time of 1974. Back-to-back testing between the B3-74 and the new 312T at Ricard-Castellet proved the new model’s superiority. When the team returned from racing the old B3-74s in South America at the start of 1975, Lauda got down to 1min 11.9sec at Fiorano, and two brand-new 312Ts were readied for the trip to Kyalami for March’s South African GP.

Lauda was sixth in Austria ’75, the flat-12 struggled in wet race after taking pole

Getty Images

Niki drove the prototype car chassis ‘018’ while ‘021’ was for Regazzoni. The intervening two chassis numbers ‘019’ and ‘020’ were, according to Ferrari, allocated to the last two B3 models. Neither of these raced; ‘019’ was heavily damaged in a testing accident and subsequently broken up, while ‘020’ went into storage for potential future display duties before sale to a private collector.

Chassis ‘018’ remains isolated as the 312T prototype, and ‘021’ began the transverse-gearbox flat-12 series, which would encompass the future types ’T2 to ’T5 and included 26 further Ferrari chassis built during 1975-80.

Lauda won the minor non-championship Silverstone International Trophy race in the new 312T’s second outing. He then added victories at Monaco, Zolder, Anderstorp, Ricard-Castellet and Watkins Glen, while team-mate Regazzoni won the minor ‘Swiss GP’ at Dijon. Such success brought Ferrari its first constructors’ title since 1964 and Lauda his first drivers’ title. Ferrari made 30 starts that season, including the initial B3 outings in South America and South Africa – where Regazzoni raced one of the older cars – and it achieved eight victories from 24 finishes. Ferrari added one second, four thirds, two fourths, three fifths, two sixths, a seventh, eighth and ninth, as well as a lowly 13th.

Lauda and Regazzoni amassed nine pole positions and six fastest laps during that memorable Ferrari season. They proved that the combination of their skills and the latest Ferrari’s power, reliability, and now handling, was by far the fastest in F1.

Lauda only failed to finish once – the Spanish GP at Barcelona, in which he and his team-mate collided on the opening lap. Ferrari’s first transversale F1 season was the more competitive 1970s equivalent of Mercedes-Benz domination in the ’50s.

This was despite the new car’s debut at Kyalami in which Lauda crashed ‘021’ during practice when he slithered off on another car’s spilt oil. His engine lacked power during the race, and it was later found that its fuel metering unit drive belt had stripped some teeth and slipped, restricting output to some 440bhp, less than the rival Cosworth DFV.

Lauda’s Silverstone victory marked the debut of the third 312T to be built, chassis ‘022’. Another new chassis, ‘023’, was then made ready for Niki’s use at Monaco and he won, despite falling oil pressure towards the finish caused by leakage through a defective pump seal. The engine was dangerously close to seizure in the final laps, with Lauda sensibly declutching and coasting through the corners, while Fittipaldi’s McLaren closed rapidly just before the finish to no avail. Regazzoni crashed ‘018’ heavily at the chicane.

Sleek 312T went against the grain with not only its gearbox, but in suspension and aero design too

RMA/Bob Harmeyer

For the Belgian GP, new exhaust systems were fitted to improve low-speed pick-up. Normally the three front and three rear cylinders on each bank fed individual tailpipes. Now a balance pipe linked the front and rear set of manifolds each side before they merged into a titanium twin exhaust. One of the pipes split in practice, so the older system was refitted. Lauda had another manifold split, and he lost 300rpm on the straights for the last dozen laps but won by 19 seconds.

“Ferrari’s power, reliability and handling was by far the fastest in Formula 1”

Anderstorp’s Swedish GP was a lucky Ferrari win. Lauda took second when one Brabham faltered, and he took the lead in the last 10 laps when the other slowed due to increasing track debris on its rear tyres, while Ferrari’s harder rear tyres were unaffected.

The fifth 312T, ‘024’, made its debut at Ricard-Castellet for the French GP but its engine failed early on, sidelining Regazzoni. Lauda drove ‘022’ away into the Mediterranean heat haze. Despite late understeer due to tyre wear, he was uncatchable.

The rain-swept British GP at Silverstone became a lottery, but Ferrari was never in contention once Regazzoni spun from the lead and Lauda had a bungled stop for rain tyres.

Into the unknown: Niki Lauda hits the streets of 1976’s new F1 grand prix at Long Beach. Lauda finished second to Ferrari team-mate Clay Regazzoni

RMA/Bob Harmeyer

While Lauda had luckily won in Sweden at Brabham driver Reutemann’s expense, Reutemann won at the Nürburgring at Lauda’s expense, Niki leading handsomely until a tyre puncture. The Austrian GP was another rain-stopped farce, then for the major Italian GP at Monza, Ferrari introduced new cylinder heads to improve mid-range torque for the slow-speed chicanes. Yet one of the new engines had failed in pre-race testing on Regazzoni’s ‘024’, so Lauda’s ‘023’ used a standard unit. Regazzoni – the Italian-speaking driver – was given the ‘high-torque’ race engine. They started 1-2 and finished 1-3, Regazzoni victorious in front of a delirious tifosi while Lauda, handicapped by a minor damper problem, fell behind Fittipaldi’s McLaren after holding the lead for 45 of 52 laps. Ferrari’s finishes and Niki’s points haul sealed the titles for Ferrari and Lauda. Monza-headed engines were then used at the Watkins Glen finale.

Eleven days later, on October 26, 1975, Ferrari’s ’76 car, the 312T2, was unveiled at Fiorano. Its development was similar to the 312T, but the previous year’s cars would run into the first races of the new season. For the 312Ts, this meant the 1976 Brazilian and South African GPs, as well as the US GP West at Long Beach, plus two non-championship British F1 races. The T2’s actual debut came at Brands in the Race of Champions in March.

Chassis 023’s last race was the US GP West at Long Beach, before a short spell as a spare car

RMA/Bob Harmeyer

The Brazilian GP opened the new season, with Ferrari fielding 312Ts ‘023’ for World Champion Lauda and ‘024’ for Regazzoni, the Austrian winning from pole while Regazzoni led before a stop to change a damaged tyre. At Kyalami, Regazzoni’s ‘022’ broke its engine, while Lauda’s ‘023’ was hampered in qualifying by an oversized tyre, leaving McLaren to steal pole. Lauda led the race, but from lap 20, his car’s left-rear tyre began to deflate. His brake balance reversed during the race yet, by clever use of lapping backmarkers, he managed to hold off Hunt’s McLaren long enough to win by 1.3sec. He also set the fastest lap, but it was now evident that Ferrari’s 1976 advantage over the opposition was nowhere near as marked as it was in ’75. A new T2 made its debut at Brands Hatch while old ‘021’ appeared on loan to Scuderia Everest for Giancarlo Martini, as part of a new Fiat/Ferrari effort to bring on young Italian drivers. Martini qualified second slowest and then crashed on the warm-up lap when a brake snatched.

“Lauda beat Hunt, but Ferrari’s lead over its rivals had reduced”

The proven 312Ts ‘023’ and ‘024’ were driven by Lauda and Regazzoni at Long Beach. Regazzoni dominated as he took pole, led all the way and won, while Lauda took second after flat-spotting a tyre and gear selection woe. This was the final appearance of the factory 312Ts as the next race was the Spanish GP in which it introduced the new ‘low-airbox’ regulations to which the 312T2 had been tailored. Before that race, the Scuderia Everest 312T ‘021’ again emerged with Martini, at Silverstone. He qualified and finished 10th, marking the ignominious end to Ferrari’s original trasversale series.

Ferrari 312T

Chassis #023 F1 grand prix race history

| Date | Race # | Race | Driver | Result |

| 11.05.1975 | 12 | Monaco Grand Prix | Niki Lauda | 1st |

| 25.05.1975 | 12 | Belgian Grand Prix | Niki Lauda | 1st |

| 08.06.1975 | 12 | Swedish Grand Prix | Niki Lauda | 1st |

| 19.06.1975 | 12 | British Grand Prix | Niki Lauda | 8th |

| 07.09.1975 | 12 | Italian Grand Prix | Niki Lauda | 3rd |

| 05.10.1975 | 12 | US Grand Prix | Niki Lauda | 1st |

| 25.01.1976 | 1 | Brazilian Grand Prix | Niki Lauda | 1st |

| 06.03.1976 | 1 | South African Grand Prix | Niki Lauda | 1st |

| 28.03.1976 | 1 | US Grand Prix | Niki Lauda | 2nd |

Chassis no023 was also the T-car at the 1975 Austrian GP, plus the Spanish and Belgian GPs in ’76. It had a 100 per cent race finishing record, and won a total of six grands prix, twice the number of any other T-series chassis built between 1975-80.