The engineer behind Ferrari’s F1 legend: How Mauro Forghieri became Enzo’s right-hand man

Doug Nye hears how a young Mauro Forghieri was catapulted from the workshop shadows to become the key figure behind Ferrari’s motor racing operations during the 1960s

Forghieri in his pomp

Getty Images

Taken from Motor Sport, August 2019

Mauro Forghieri – for 27 years the chief engineer of Ferrari’s racing operation – was on fine form. Ten days earlier, this tall, rangy man of enormous accomplishment had celebrated his birthday. Now 84 – but going on 60, and bright as a firework – he had been recalling bygone events at his home in Magreta, one of the sprawling village communities dotted around the Italian city of Modena.

My Genoese friend Franco Lombardi – himself a great Ferrari and Maserati authority – was with us, and we had just driven to the neighbouring village of Casinalbo for lunch.

Forghieri is, justifiably, a well-recognised local celebrity around these parts. Franco and I were reading the lunch menu while he chatted up a pretty waitress. She gamely played along and took our order as Mauro charmed.

Here was the engineer to whom Mr Ferrari had entrusted sole technical responsibility for the Maranello racing department, back on October 30, 1961. “I remember, it was a Monday. Ferrari called me to his office and said ‘You are now responsible for all the motor sport activity and testing…’ Bam. Just like that,” says Forghieri. “I was only 26. How could that be? I told him ‘Are you mad? I don’t have enough experience.’

With Enzo Ferrari and Chris Amon during the 1965 Italian Grand Prix

Getty Images

“But Ferrari said ‘Listen – you just do your job and I’ll do the rest.’

“I had worked a short time at Ferrari as an intern in 1957, when Andrea Fraschetti was chief engineer, but after completing my engineering degree at Bologna University my dream was to join a gas turbine company in America.

“My father Reclus worked at Ferrari for many years. Ferrari had sometimes asked my father how I was doing at university. And finally – as I waited to hear from America – Ferrari told my father he wanted to see me. He told me that Fraschetti – who had been killed testing a car at Modena in 1957 – had spoken well of me. ‘Why not come and work here to gain experience, at least while you wait for America?’ I joined in January 1960… and stayed until 1987.”

His startling elevation followed the infamous ‘palace revolution’ at the end of the 1961 season, when chief engineer Carlo Chiti, team manager Romolo Tavoni and five other senior figures were summarily shown the door. They had tried to present a united complaint to Mr Ferrari about the increasingly erratic interference in their duties by Signora Laura, his quite dotty wife and co-owner of the company. But too fearful to complain to the Old Man’s face they had engaged a local lawyer to write a letter to him, which they all then signed.

Forghieri completing checks on a 1512 at Silverstone, 1965

Getty Images

This was taken as a less than manly affront, while such internal – indeed ‘family’ – matters with a lawyer, an outsider, were utterly unacceptable.

Mr Ferrari did not explode into one of his celebratedly theatrical rages, his screaming normally being audible many metres from his office. His response was much more frightening. He just grimly had a quiet interview with each of the seven, and as they left another functionary handed them each a notice of immediate dismissal. With the Ferrari team and top echelon decapitated, Forghieri was given command.

He recalls: “I was dazed, but excited. And I had confidence in the great technicians there. During my intern period back in 1957, Fraschetti was considering a rear-engined car as one option for racing. Of course, he worked – with the great Alfa Romeo and Lancia designer Vittorio Jano contributing – to develop the first Dino V6-cylinder cars for Formula 2 and then Formula 1. He gave me the centre section of a chassis frame to design and to do the stress calculations and so on. I think that was for the V6 monoposto. He taught me the importance of having a rigid chassis.

“Jano was the consultant. He would come down to Modena from his home in Turin and stay for a few days at a time in the Hotel Albergo on the Via Emilia. You say he is remembered as having been a very cold and serious man. I can only say he was very human to me. And in fact, so was Laura Ferrari – she was always very nice to me, too.

“Luigi Bazzi was also from pre-war Alfa Romeo. His daughter married a friend of mine. Bazzi had the greatest and widest experience. He was capable of doing everything in the factory, and I mean everything – tutto! He was always thinking and questioning and suggesting. And his ideas were always good. For any question, any problem, Bazzi could find a solution.

“I had learned from all their great experience. And there were the other engineers, like Angelo Bellei and Franco Rocchi – Jano and I did the Formula 1 V8. When the project began I asked for him to become involved. Bellei was in the production department, in charge of road car design and development. But we were all really friends working together. Casoli worked on millimetri [millimetres] – such was his eye – and he was great for modelling too – he came from Reggiane, the aircraft maker. And Bazzi was in the test department.

“Enzo Ferrari had loved the 12-cylinder Packard. He never forgot that. The V12 has a natural balance, and a V12 is easier to design and to set up but expensive to manufacture. Chinetti and other friends encouraged Enzo Ferrari to build a V12. The Banco di Modena and other friends provided the money for him to do it.

“Many of his early workers were drawn from Minganti in Bologna, the big machining company. Hah – they had a good basketball team. I used to play basketball to a good level. In 1939 my father worked with Bazzi, Giberti and Ferrari in his small factory in Modena, making the parts for what became the Alfetta. I think they made four of them. And this car became almost unbeatable. My father worked specially in the Alfa Romeo factory and after the war with Ferrari he became chief of the machine shop.

Bandini ready to go in front of Forghieri and Phil Hill at the Nürburgring, 1962

Getty Images

“When I was small my great interest was aeroplanes. Into my teens I was always drawing planes, but never jets. I thought they were boring. Nothing to see. All the planes I drew had propellers. Papa made propellers during the war…”

Tall bespectacled Mauro would grow quickly into his chief engineer role, known for his colourful, sometimes explosive personality, for his diligence, his imaginative design talent and above all for his industry. It was under his leadership that Ferrari replaced its obsolete-technology ‘sharknose’ Formula 1 cars of 1961-62 with the lightweight spaceframe, fuel-injected V6 cars driven notably by John Surtees and Willy Mairesse in 1963. He also masterminded development of a sweet-handling rear-engined V12 sports-prototype in the P-cars of 1963-64, leading on to the P2-3-4 designs of 1965-67.

For the Ferrari 158 and 1512 F1 designs of 1964-65, Forghieri took Ferrari into ‘aero’ monocoque chassis construction with the stressed aluminium skin panels riveted to an easily repairable frame of small-diameter tubes. He and his colleagues designed the little 1600cc and 2-litre Dino V6 prototypes, and then 3-litre F1 V12s for 1966-68. He directed the programme in which the front-engined 250 GTO series culminated in the roofed-in rear-engined 250LM Berlinetta.

“Ferrari had a great understanding of human weakness”

We talked in broad-brush terms about his career, with some specifics in sharper focus. He speaks with genuine fondness of Mr Ferrari. When the Old Man died in 1988 and I had to write an obituary, I had asked Mauro to comment on what had been Mr Ferrari’s greatest talent. After much thought he replied, slowly – “He was a man with a great understanding of human weakness.” Words he left unspoken could have been – I believed – “and how to exploit it…”

It is plain that over their many years as employer and chief engineer, Ferrari and Forghieri fought many battles, as often with one another as they did united against outside rivals. Mauro: “He would make his unhappiness absolutely clear and he would certainly shout and scream. But even from quite early, because he knew my father so well and had known me from such a young age, I was able perhaps more than some others to shout and scream straight back!

The 1967 330P4

Getty Images

“My father was a strong man. All the Forghieri men have been strong – strong opinions, strong views, not afraid to state them. My grandfather had been a close friend of the young Mussolini, but later their political views moved apart. My grandfather left Fascist Italy and lived in France, where he wrote some very critical things about Mussolini in the French newspapers. I remember my father then coming home several times, injured, having been beaten up by the Fascists.

“He would have heard them criticising his father, so he would stand up for his Papa and they beat him. But even then he would not keep quiet. It got so bad that he was advised to move out of Modena, to somewhere quiet for him and for his family. We ended up for a while in Naples, but through much of the war we were in Monaco where my father serviced and repaired high-quality cars – Hispano-Suiza, Alfa Romeo, that kind of thing. The big man of the regime in Modena helped us move to Naples, where father worked in the Ansaldo aeroplane plant. We had quite a nice house there in the Parco Caruso area, 20-30 houses in the Arco Felice village.

“I loved the place. I would draw designs for planes there – always propellers of course – and then started two years of university in Modena, studying maths and physics. I got a place in the University of Bologna to study mechanical engineering. It had fewer than 600 studying all disciplines, so it was an honour to go there. The professors were really very good. Some were often called to the US to consult on their specialities…”

With John Surtees at Le Mans, 1964

Getty Images

From 1948, Ferrari’s racing programme was always designed to promote sales of the production cars, which income was reinvested in further racing, year upon year.

“Racing against Ford at Le Mans was both difficult and expensive”

Mauro: “After Ford America had failed to buy the company in 1964, Fiat gave a little more support but racing against Ford at Le Mans for example was difficult and expensive. You ask which of our cars I recall most proudly? The P4 sports-prototype. But that was an expensive project. It diverted too much attention and too many resources from F1. We had to stick with the V12 engine through 1968-69 when it was outdated technology, too long, too heavy. Then the Fiat-Ferrari deal was made and I saw how happy Ferrari was with that result. He took me away from direct responsibility for racing and I worked in a new Advanced Studies Office, first in the old Scuderia building in central Modena, then later at Fiorano.

Le Mans 1967 with the P4

Getty Images

“With a small group of designers and technicians – Salvarani, Maioli, Marchetti, Panini, Lugli and Piccagliani – we worked on what became the 312B flat-12 for 1970. We worked on a four-wheel-drive scheme for it. Ferrari wanted to demonstrate our advanced technology to Fiat but we ran out of time, so came out with rear-wheel drive only – then the FIA banned four-wheel drive! The flat-12 project had also been started with the American Franklin aero company interested, but they did not last long.

“Ferrari always loved engines and paid close attention to our progress, and I would see him every day. The 312B cars with Ickx and Regazzoni were very good, but began winning too late in 1970, and after a good start to 1971 we had terrible trouble with Firestone tyre vibration. Suspension changes I had made were partly blamed, in connection with the tyre troubles.

Our results dropped. Ferrari and I – well, there was much screaming from both sides. Fiorano had just opened and the Advanced Studies Office and I were moved there. Ferrari fell ill. Fiat put Sandro Colombo in charge of the racing side and in 1973 the first Ferrari B3 was really bad.

“Ferrari then recovered. He was back – full of energy – and he called me back to improve the B3 while producing the Advanced Study for a way forward in F1 – which was the B3 ‘Snowplough’.

Clay Regazzoni, 1976

Getty Images

“I calculated that the aerodynamic downthrust of a full-width sports car body was so much greater than the slender cigar F1 designs of that time, that we should make a surface form about 75 per cent that of a sports car, with a merged-in front wing, central mass concentration, radiators each side between the front and rear axles and short wheelbase for agility. From this test car came the B3 of 1974, which Niki Lauda and Clay Regazzoni showed could win, and then the next step was the transverse gearbox 312T of 1975 – and our first F1 World Championship since Surtees and our V8 in 1964. I would say the 312T, the P4 and of course the 312P Boxer sports of 1971-72 are the most satisfying Ferrari designs for me…”

Tantalisingly, in any conversation such as ours, one can merely scratch the surface of Forghieri’s long, busy and often dazzling Ferrari career. Latterly, into the 1980s, he found himself presiding over younger, variably capable, ambitious and forceful engineers, each eager to stamp their own design signature upon the Prancing Horse. For some of them Forghieri became old-school, an obstacle. Some he found simpatico, others not. He recalls: “Harvey Postlethwaite came in from England to introduce us to aluminium honeycomb chassis technology. It was good but very quickly we realised carbon composite could be better still. I say to Harvey, ‘OK now what experience have you got with carbon composite?’ – and the answer was almost none! So we learned together. But Harvey fitted in very well with the Ferrari way, with our ‘family’. The language of the factory had never been simple Italian, but Modenese dialect which can be very different. Harvey learned it in weeks. He was very popular. Others did not fit so well…”

They had the Lauda years, the Gilles Villeneuve flair that ended in catastrophe and the V6 turbo years. Forghieri also found himself spending much time protecting Ferrari’s interests in FISA/FOCA political conflicts and debating with the FIA itself, as well as masterminding and directing new racing designs.

At just 26, Forghieri inherited all of Ferrari’s racing activities

Getty Images

Frictions with Marco Piccinini and Piero Lardi – Mr Ferrari’s natural son – led to Mauro regretfully (yet perhaps typically noisily) telling the Old Man he wanted to resign. Vittorio Ghidella of Fiat suggested a change of departments, from racing to Ferrari Engineering. Mauro worked two final years with Ferrari away from F1, but often Enzo would seek his opinion and reaction to matters arising.

The final Forghieri Ferrari was 1987’s 408/4RM prototype, which was displayed at the Detroit Motor Show. It was judged too complex and innovative to enter production and Maranello built the 348 instead. Fiat’s Ghidella – whom Forghieri had come to count as an ally – was beset by mainstream Fiat problems into 1987 – the Old Man had lost much of his once-total power and was fading fast. Ferrari at Maranello and Fiorano had become a much-changed company.

At the Geneva Motor Show, sometime Ferrari racing director Daniele Audetto met Forghieri and told him that Chrysler’s Lee Iacocca wanted him to work for their latest acquisition, Lamborghini. After his 27 years and five months at Ferrari, Mauro accepted. One detects enduring hurt over the fact that some of his long-time colleagues there did not, ultimately, show as much support for him as perhaps he would have shown for them – but still he has many fond memories.

Forghieri talks with Gilles Villeneuve in his 312T4 at Zolder in 1979. The Canadian would take three wins and finish second in the championship that season

Getty Images

“We were truly a family. Our life was our work, total commitment… for little pay. We were not just colleagues… we were brothers. There were a few days when our work succeeded and results made Ferrari very happy. There were days when he was not.

“Ferrari would shout at us, and some of us were able to shout back. Many were not willing to”

“Strangely Ferrari was much more on our side when we were losing. When we were winning he would drive us hard. He would shout at us. Some of us were able to shout back. Maybe not many were willing to do that. But I was both able and willing…and I did shout back at Enzo Ferrari and – sometimes – he would listen and come around to supporting me. At other times… well, not so much.

“But I am happy with my life experience. And I am always thankful for the huge confidence that Ferrari had always shown in me…”

Forghieri’s fabulous designs

Mauro Forghieri co-created some of Ferrari’s greatest cars. Here are his three favourites – plus two more (Dino and 158) that we chose

1964 Ferrari 158 ‘Aero’

Designed with and for John Surtees, the ‘Aero’ 158 had a semi-monocoque fuselage in which a lightweight internal tubular frame was stiffened by riveted-on aluminium stressed skins. Its 1.5-litre 4-cam V8 was another small masterpiece encouraged by veteran consultant Vittorio Jano. Development came good late-season in 1964 as Il Grande John won the German and Italian GPs and clinched the World Championship.

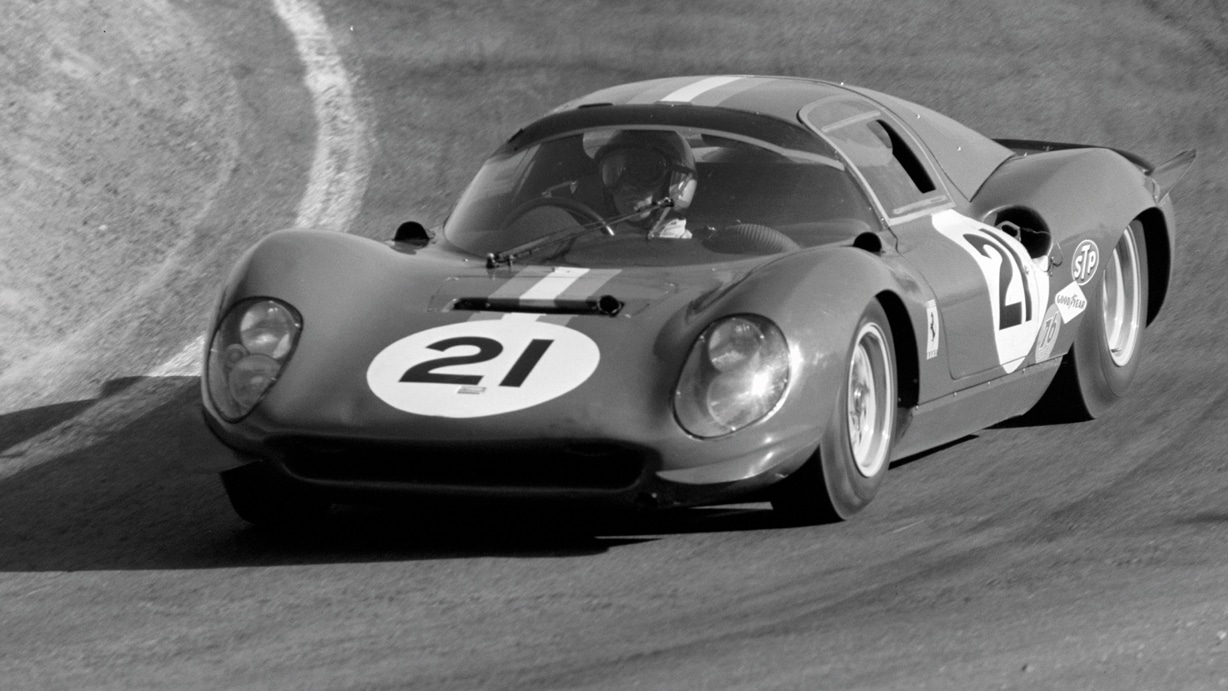

1967 Ferrari 330P4

The ultimate P-car of the rear-engined V12 sports-prototype series Mauro had developed from the initial 3-litre V12 250P of 1963. Input from such drivers as Surtees, Parkes, Scarfiotti, Bandini and Amon helped the World Championship-winning 250Ps, the P2s and P3s culminate in the definitive big-budget 4-litre, 4-cam 330P4. This car crushed Ford at Daytona ’67, finished 2-3 at Le Mans and won the 1967 world title.

1972 Ferrari 312PB

Forghieri’s Ferrari flat-12 cars ranged from the original 1.5-litre 1964-65 F1 1512, through the 2-litre 1969 European Mountain Championship-winning 212E to the 3-litre 1970-80 312 F1 series. In 1971 the 312PB ‘thinly disguised F1’ sports-prototype had some sensational outings driven by Ickx and Regazzoni. For 1972 Ferrari ran a full works flotilla of flat-12 312PBs, winning every World Championship race they entered – a tour de force…

1975 Ferrari 312T

Mauro cites the magnificent 1975 F1 World Championship-winning 312T as the single-seater design of which he is most proud. A flat-12 with its central mass concentration augmented by the transverse gearbox, it carried Niki Lauda to his first F1 title, winning the Monaco, Belgian, Swedish, French and US GPs in his hands. Team-mate Clay Regazzoni won Ferrari’s home Italian GP. The 312Ts then followed up by winning the first three GPs of 1976.

1966 Ferrari Dino 206sp

Forghieri tends to dismiss this enduringly gorgeous little 2-litre V6-engined sports-prototype design as having been a hurried, imperfect and never fully developed expedient to give Fiat a Porsche-bating campaign to back the production Dino model’s marketing. However, these compact, agile, elegant little P-cars in miniature have a glamour that no Porsche can approach…