Ferrari’s first world champion: Alberto Ascari

The first back-to-back grand prix world champion, who duelled with Fangio. Alberto Ascari is unarguably one of motor racing’s all-time greats

Ascari during the 1952 British Grand Prix at Silverstone. He started on equal pole after both he and Ferrari team-mate Giuseppe ‘Nino’ Farina set identical 1:50sec laps. He went on to win by a full lap in his 500

Getty Images

Taken from Motor sport online, September 2020

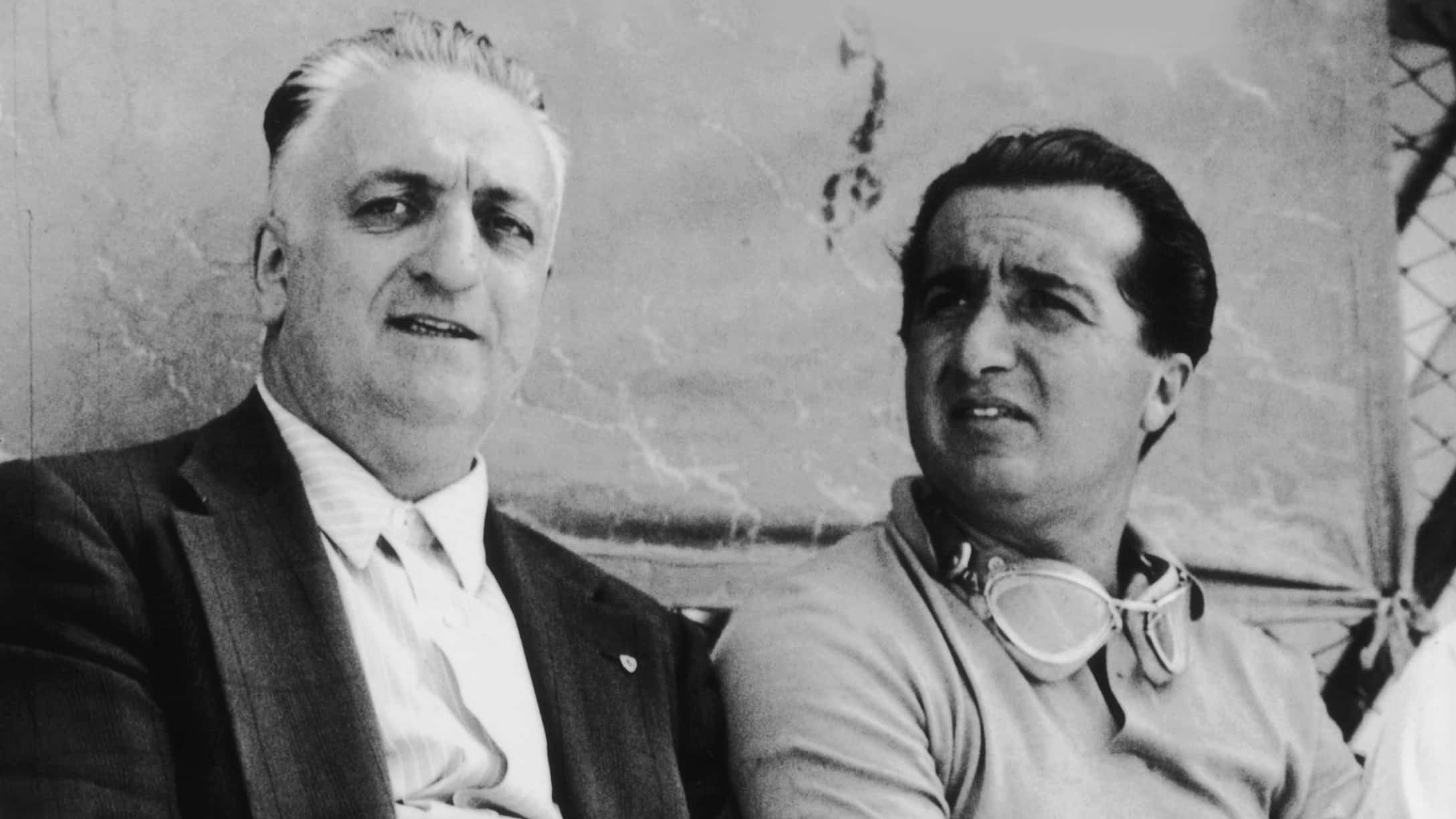

Alberto Ascari drove racing cars as though born to it – which, of course, he had been. Father Antonio – much admired by the formative Enzo Ferrari – had until his fatal accident of 1925 fleetingly been the world’s best driver. His son, however, would outstrip him before he, too, was killed at the wheel.

Career delayed by World War II – he had, however, driven a Ferrari in all but name in the emasculated Mille Miglia of 1940 – Alberto was turning 32 by the time of the World Championship’s inauguration in 1950. Young in the context: Juan Fangio was seven years his senior.

For the next four seasons the debate would rage as to which of these two was the better. It was nip and tuck.

But for a misguided tyre swap in the 1951 showdown at Barcelona, Ascari might have denied Fangio a first world title. Handed a car advantage by Ferrari for 1952 – and in Fangio’s absence due to a broken neck – he then dominated that season and much of the next to become the first back-to-back world champion.

“His racing MO was to jump into an immediate lead, demoralise the opposition, and control things from there”

His racing MO was to jump into an immediate lead – in the manner of Clark or Stewart – swiftly demoralise the opposition and control proceedings thereafter. Mistakes were few and far between. It was in this manner that he won nine consecutive grands prix.

If there was a weakness in his armoury it showed in the 10th race of this sequence: he led not a single lap in finishing a close fourth in the 1953 French GP at Reims – the Race of the Century – and it was left to his younger, less experienced team-make Mike Hawthorn to take the fight to – and win against – the increasingly competitive Maseratis of Fangio and Froilán González.

Ascari could ‘tiger’ (Jenks-speak for battling with controlled desperation against long odds) as his charge to that year’s title at the fearsome Bremgarten in Switzerland proved. But that he then tripped at the last corner in a four-way scramble – Maserati’s Onofre Marimón was several laps adrift and should have butted out – for victory at Monza confirmed the suspicion that he wasn’t entirely comfortable in a dice situation.

We are picking holes here.

Feeling under appreciated by Enzo – continual success had bred complacency at Maranello – Ascari allowed himself to be wooed by Gianni Lancia’s overly ambitious vision of F1’s future and thus spent much of 1954 on the sidelines. He qualified on the front row at Reims when loaned to Maserati, and was leading at Monza upon his one-off return to Ferrari when the engine let go. And when finally Lancia’s D50 arrived, albeit in a less radical form than had been mooted – needs must – Ascari put it on pole at Barcelona and led until gremlins struck early.

Continuing reliability niggles – Lancia had overstretched and was feeling the pinch – blighted the launch of his 1955 campaign, too. Rival Mercedes-Benz had in the meantime upped its game, not least by the signing of Stirling Moss in support of Fangio. Ascari was under pressure like never before.

Having survived GP racing’s most memorable crash – bobbing to the surface after his car had plunged into the Monaco harbour – Ascari attended Eugenio Castellotti’s test of a Ferrari sports car that they were to share in the Monza 1000km. There was no suggestion that he was scheduled to drive it that day.

Ascari was not only a stickler for detail – as evinced by his neat style behind the wheel – but also he was extremely superstitious. Yet he chose to tempt fate – and crashed to his death in a borrowed car while wearing a borrowed helmet. He was just four days older than his late father – both having met their maker on the same day of a month. That’s just spooky coincidence. What’s amazing – and indicative – is that car-crazy Italy has yet to nurture a driver of similar status – although Ascari did inspire a certain Mario Gabriele Andretti prior to him pursuing his ambition and talent in America.