Porsche’s shock win in Targa Florio’s final blast

In 1973 the final world championship Targa Florio was run along Sicily’s mountain roads, ensuring the race and the winning Porsche 911 RSR a place in history. Fifty years on Paul Fearnley tracked down Gijs van Lennep to relive his bitter-sweet victory

Getty Images

Taken from Motor Sport, August 2023

Porsche had gatecrashed the Targa party a total of 10 times since 1956. The word on the streets of Cerda, Collesano and Campofelice, however, was that an 11th win was highly unlikely. For not only was Porsche’s ‘prototype’ sports-racer of 1973 nothing more than a souped-up GT car, but also the 57th running would likely be the final flowering of Sicily’s throwback road race.

“I think we knew that it would be the last one,” says Gijs van Lennep, the Dutchman slated to share the fastest of three works Carrera RSRs with Swiss Herbie Müller. “But that didn’t matter to us beforehand. We were just practising, practising, practising: a whole week; at least five or six laps a day. We never thought about winning because of those 12-cylinder Ferraris and Alfas, but we knew that we should finish because ours was a very reliable car.”

Van Lennep takes in the memories of his Targa Florio-winning Porsche 911 RSR

Klemantaski Collection

Van Lennep is now 81. Dubbed the best Dutch driver of the 20th century he can count two Le Mans wins plus a handful of Formula 1 starts for Williams and a European F5000 championship to his name. But he is proudest of his Targa victory.

Van Lennep’s three previous Targa starts from 1970 had involved full-shot prototypes: fourth on debut in Racing Team AAW’s Porsche 908/2, co-driven by ill-fated Finn Hans Laine; second in the Alfa Romeo 1-2 of 1971 aboard a T33/3 co-driven by Andrea de Adamich; and a crushing first-lap retirement because of a blown engine when “all geared up to win” alongside Vic Elford – “the world’s best all-round driver” – in an Alfa T33/TT/3.

An RSR was a very different proposition. Porsche’s endurance hand had been forced by the introduction in 1972 of a 650kg minimum for 3-litre prototypes. No longer able to compensate for a lack of power and therefore compete with the F1-engined ‘two-seater grand prix cars’ of its rivals, Stuttgart chose instead to race, develop and promote its new-generation 911 road rocket.

Careful on the gearbox, not so on the tyres. Van Lennep lifts a wheel as he makes the most of the RSR’s traction

Biasioli

“We spent two weeks in January at Paul Ricard: we made the RSR, more or less,” says van Lennep. “We changed the whole rear suspension: sawed it off, welded it back on, etc. Meanwhile: ‘OK, Gijs, the other car is ready with 40 litres. Empty it!’ Another 40 laps. Tired after every day, but I was in fantastic condition by the end of it.

“Testing was so good with Porsche. They would change something on the car that made it two-tenths faster. Then they took it off, and you would be two-tenths slower. Put it back on: two-tenths faster. Only then would they move to the next thing. That’s how we did it.”

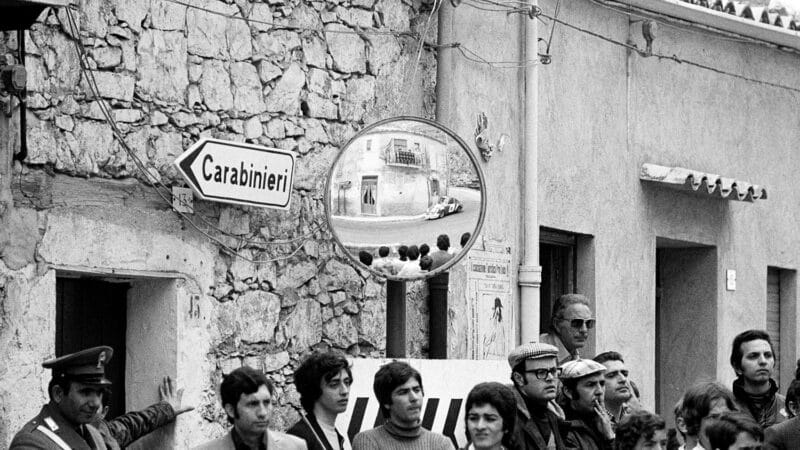

Even the local Carabinieri indulged in spectating

Getty Images

More often entered as a prototype to allow freedom of development with a view to improving the breed without upstaging loyal GT privateers, the base result was an extra 30bhp for 50kg fewer: 330bhp on (eventually) slide throttles; and 890kg, minus a spare wheel.

Though visually similar bar a duck-tail spoiler extended to the body’s full width, plus muscular arches containing wider tyres on centre-lock mag-alloy rims from the Can-Am 917/10, much was changed under the skin. There was lighter, stiffer aluminium rear semi-trailing arms with rubber bushes swapped for Unibal spherical joints; upper front suspension struts adjustable for camber and caster; stub-axles mounted higher on the strut for lowered ride height; stiffer, variable-rate titanium springs with Bilstein dampers; and Porsche four-pot calipers clamping ventilated and perforated discs on titanium hubs, also taken from the 917/10.

Rolf Stommelen/Andrea de Adamich’s prototype Alfa should have walked it, but crashed out

Biasioli

The air-cooled flat-six, bored out by 3mm to 2993cc and red-lined at 8000rpm, featured cam-adjustable Bosch fuel injection, twin-spark heads with larger ports and valves, wilder cams and a 10.3:1 compression; titanium deemed too expensive, its conrods were polished steel. Power was fed from a single-plate racing clutch to a limited-slip differential via a Type 915 five-speed gearbox that was standard bar ratios and a front cover incorporating an oil pump circulating through a separate cooler.

Though operating in somewhat of a category limbo, this very handy weapon scored a sensational victory on debut – even before its GT homologation date – at February’s Daytona 24 Hours, courtesy of Florida’s Brumos Racing and drivers Peter Gregg and Hurley Haywood. Martini Racing’s campaign in the European rounds of the World Sports Car Championship began with an eighth place at Vallelunga in March, followed by: ninth at Dijon-Prenois; a rare retirement (engine) at Monza; and fifth at Spa-Francorchamps. Van Lennep and Müller also won the non-championship Le Mans Four Hours held after the official April test.

RSR interior

DSC

The Targa Florio, with its innumerable twists and turns, incessant lumps and bumps, was ideal RSR territory – yet in official practice it was still more than 3min slower than the fastest true prototype, 1972 winner Arturo Merzario’s Ferrari 312 PB having got within 2.5sec of the lap record. Porsche’s long shot, however, shortened somewhat when Clay Regazzoni, new to this island race, somersaulted an Alfa Romeo T33/TT/12 to destruction.

There must have been something in the Madonie mountain air (the circuit rose to 1970ft): Andrea de Adamich crashed the second Alfa, albeit with less serious consequences: suspension and bodywork; Jacky Ickx, also on Targa debut, was seen driving a Ferrari minus its nose; and pacesetter Merzario was halted by a failed fuel pump. Porsche wasn’t immune either: Giulio Pucci, son of Porsche’s 1964 winner Antonio, wrecked his RSR and would race a T-car/bitsa.

The second-placed Lancia of Sandro Munari/Jean-Claude Andruet

McKlein / Reinhard Klein / Colin McMaster 2021

Van Lennep’s was an oasis of calm in comparison: “[Unofficial] practice was more dangerous than the race. For there was something around every corner: ladies dressed in black on a mule getting wood for the burner; or sheep all over the road. I crashed an Alfa road car once. Ill with fever, I shouldn’t have been driving. But no: ‘Take my car! Do half a lap and then go to the hotel.’ I met a lorry. It didn’t go very well. No injury. No problem. But the front wheel on my side was back a bit.

“Unofficial practice was more dangerous than the race”

“Herbie was a very professional guy and a really good driver. He had won the Targa in 1966 in a Porsche 906 co-driven by [Willy] Mairesse, so he knew where to go. Ours was a good match. I don’t think there was much difference in our heights: I’m 176cm [5ft 9in] and he was maybe 2cm shorter. So our seats were the same. Actually, maybe I had a bit more padding because my back was not so good. We both set the car up, too; we were always the same like that. We did springs and shockers, softer, softer all the time, so that it was like a road car over the bumps. We made it very easy to drive. We had a long first gear for the hairpins – the RSR was heavy but had good traction – and a short second, third and fourth, very close together so that we were always in the right rev range, and a long fifth for the long straight. Most of the time we were using second and third. The change was a bit heavy because of the synchromesh, but not too bad. Plus we were young, strong guys.

Abele ‘Tango’ Tanghetti’s blazing Chevron

Getty Images

“Even so, it was more physical than Le Mans. You were not going so fast, but that didn’t matter. You soon get used to velocity. At the ‘old’ Le Mans we used to say that we had 6km to rest every lap – even at 355km/h [220mph]. The Targa was very tiring: 700-800 corners and 1500 gear-changes every lap. It kept you busy. The weather was hot, too. And we had no drinks in the car.”

Concentration was key to this time-trial – cars were released individually at 20sec intervals – on a 44.7-mile circuit littered with every conceivable hazard and lined by spectators. The fastest Porsche operated as though in a bubble while others’ dreams burst: Merzario, paired with Sicily’s own Nino Vaccarella, suffered a rear puncture on the first lap and soon would retire because of a broken driveshaft likely caused by running on the rim; Ickx, bemused by the whole scene, landed in a ditch on the third lap; and de Adamich, having inherited a large lead after three laps by co-driver Rolf Stommelen, promptly wrecked his front suspension against a Lancia Fulvia.

“The Targa was very tiring: 700-800 corners and 1500 gear-changes every lap. It kept you busy”

“We were second when I got in the car,” says van Lennep. “[Andrea] must have been so angry. He could have won so easily. But I was happy he was out. He had been cross with me in 1971. He asked my wife, ‘Why did Gijs not go a little faster on the last lap? We could have won!’ But we were 1-2 and I was happy with second, 1min behind. Plus Carlo Chiti [the boss of Autodelta] was very happy with me because I drove three laps within 9sec of each other. Plus it was orders. Vaccarella was to win. Normal. So we took it easy. I knew exactly what to do. So this time I was thinking, ‘OK, this is justice.’”

Balcony views as Alfa Giulia GTA flashes past in 1973. Mario Litrico and Ferragine finished 20th

Balcony views as GP Library Limited / Alamy Stock Photo

Seven surprisingly lonely laps lay ahead and the right balance had to be struck: “I can’t remember seeing anybody; OK, maybe some small Lancias. I didn’t catch one and nobody came after me. The people in slower cars were looking out for you and would let you past. And there were marshals with flags. So I had no fights on the track.

“Now you knew no lorries were coming. Even on blind corners, you could use all of the road”

“The other funny thing was that you had practised all week – but now you were on a new sort of track. During unofficial practice you had been much slower – though still too fast actually – because often you used only half of the road, just in case. But now you knew that no lorries were coming and, even on blind corners, you could use all of the road. Different lines in lots of places and suddenly 4-5min faster: a big change.

“[Forever] lap record-holder Leo Kinnunen was in our second car, so we couldn’t slow right down. We were 8min in front of him by the end, so Herbert and I must have been driving very fast – but not too fast. That’s what we were very good at: keeping concentrating. Full focus. One little mistake on the Targa could be vital.

“Ickx was one of the best ever – a great guy. I won Le Mans with him in 1976 – but he didn’t know the Targa very well; or not good enough at least. He didn’t test very much. I don’t think he liked it. Whereas I liked it a lot. I liked to do rallies in the winter – five Monte Carlo and five Tulips – and I am a bit of a street racer. I am very precise, or at least I try to be. That’s what the Targa needed. You can always make a mistake, of course, but you are not supposed to.

Van Lennep and Herbert Müller celebrate the spoils in 1973

LAT

“I did a lot of racing with Herbert in 1973 and 1974, and he never made a mistake. He made our fastest lap in this race. He did three laps. Then I did three. He did three more and I did the last two. If you added our three laps together our times were exactly the same. I was a bit more consistent.

“And the team thought maybe I was a bit easier on the car. I always said, ‘Be nice to the car and the car will be nice to you.’ With Porsche’s gearbox, you have to wait in the middle a bit. You don’t win races like these by changing gear ridiculously fast. You must go faster through the corners; tyres, you can put on again quickly.”

But no mistakes were forthcoming. The remaining laps were reeled off, and the winning margin over the Lancia Stratos crewed by Sandro Munari – a winner in 1972 – and Jean-Claude Andruet was more than 6min. It might have been closer had not these renowned rallyists been hampered by a broken seat. No matter, Porsche had turned it up to 11.

“Win a big race in a car that looks like a road car and it’s good PR,” says van Lennep. “The locals liked to have an Italian car winning, of course, but they were pleased for us. OK maybe not completely. But, yes, they were excited. If you win the last Targa Florio – and I have been five or six times to Sicily in the last 50 years – you are a hero there. The older people know – the latest generation doesn’t know so much about the Targa – but even today if you stop in a town square to have something to eat and drink somebody will recognise you: ‘Gijs!’ In no time at all 200 people will come from everywhere. It’s very nice.

“The locals liked to have an Italian car winning but they were excited for us”

“You can win Le Mans – I did twice – but if you win the Targa Florio, especially the last one, for me it is the better achievement, even though Le Mans is the bigger, more important race.”

It was hoped that the CSI meeting scheduled for Indianapolis might save the Targa Florio; there was talk of a new purpose-built track. Instead, unable to meet new mandatory safety requirements, the Piccolo delle Madonie circuit was stripped of the World Sports Car Championship status that it had held for almost 20 years. The deaths of British privateer driver Charles Blyth in 1973, whose Fulvia collided with a Fiat towing another competitor’s 911S during unofficial practice – Merzario was one of the first on the scene of the accident – and of a spectator mowed down by an Italian-driven Renault-Alpine had in truth ended any hope of a reprieve.

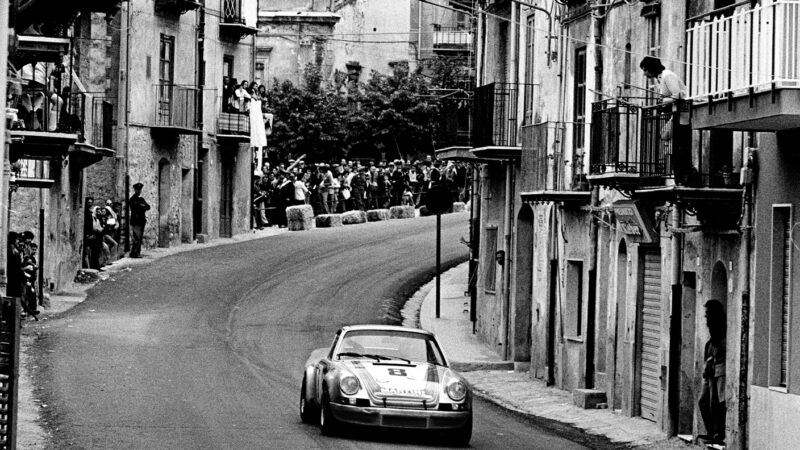

No traffic through town: unlike the daunting unofficial practice days, race cars ran unimpeded through the streets

Getty Images

Remarkably, given the race’s brutal nature, just nine people were killed across its 61 runnings from 1906: five drivers and a riding mechanic plus three spectators. But a growing feeling was that it was trusting too much to luck.

“The crowd were right by the side of the road. What if something broke?”

“The spectators were right on the side of the road,” says van Lennep. “Parked, sitting everywhere. They were so keen. But they were never crazy like a rally crowd. There was none of this dancing in the middle of the road. But what if you get a sudden flat or something breaks? One day someone was going to take out not one, but 10, 20, 30 people.”

Targa struggled on as a national event for four more years, but the big names drifted away. When an Osella not prevented from running minus its rear bodywork and integral wing crashed into the crowd in 1977, killing two and injuring several, the Carabinieri stepped in to stop the race after four laps. Even the locals knew this game was up. What replaced it was a stage rally, which from 1984 to 2011 would hold European Championship status.

“It was a good decision,” says van Lennep. “But I would have gone back [in 1974]. Because it was not so fast: about 220kph [135mph] by the end of the straight. We did a 125 fastest lap in the race and, with stops for tyres and petrol, averaged 115. At Spa, we averaged 245. That was dangerous. I would never go back there. But the Targa? I’d go there today if I could. It’s in my heart.”

Friends reunited

The day van Lennep and R6 returned to Sicily

What do you do if you have just finished restoring one of the most important Porsches ever to turn a wheel, back to the spec in which it achieved its most enduring victory? If you are Lee Maxted-Page, founder of the eponymous Porsche specialist, you put the car on a lowloader and return it to the scene of its triumph.

Van Lennep’s 911 had been restored to 1973 condition – he was impressed

Maxence Massaro

“We thought it would be rude not to,” says Lee of his decision to ship the Porsche 911 RSR (known as R6), from the company HQ in Essex to Sicily. “We just rocked up with the car – it wasn’t road registered – and we also brought Gijs van Lennep with us. It was a very cool day. At one point the police turned up and asked us what we were doing, but when we explained that this was the car that won the last Targa Florio they said, ‘Fine!’”

Maxted-Page spent months restoring the car back to its Targa Florio specification after it had been rediscovered in the US. You can read about the project as it got underway in the May 2018 edition of Motor Sport. The finished car is a remarkable tribute to van Lennep’s victory: “We got Norbert Singer’s race notes from the factory and returned the car back to the very same set-up it had in April 1973. Gijs couldn’t believe it – the gear ratios, everything, was as it was when he last drove it.”

The Maxted-Page team didn’t stick around too long in Sicily however: “After a while you got the feeling that you were being watched,” he says. “We didn’t want to outstay our welcome.”

The restored car’s latest outing was at the far less menacing Goodwood Members’ Meeting, which you can read about overleaf.