Reliving the Mercedes-Benz vs. Auto Union Rivalry Through Bernd Rosemeyer’s Legacy

Few motor racing battles have such enduring appeal as those between Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union. It was arguably the most courageous chapter in Grand Prix history, and Bernd Rosemeyer became its very essence

Audi

Taken from Motor Sport, June 2013

Thirty or so years ago I wrote a column for Autosport about Bernd Rosemeyer, long dead before I was even born, yet the figure of legend who first captured my imagination, triggering a life-long love affair with motor racing.

Soon afterwards, in the Zandvoort paddock, Murray Walker told me he had enjoyed the piece and had something he wished to give me. He then opened his case and handed me a single sheet of paper. When I took in what it was, I reeled.

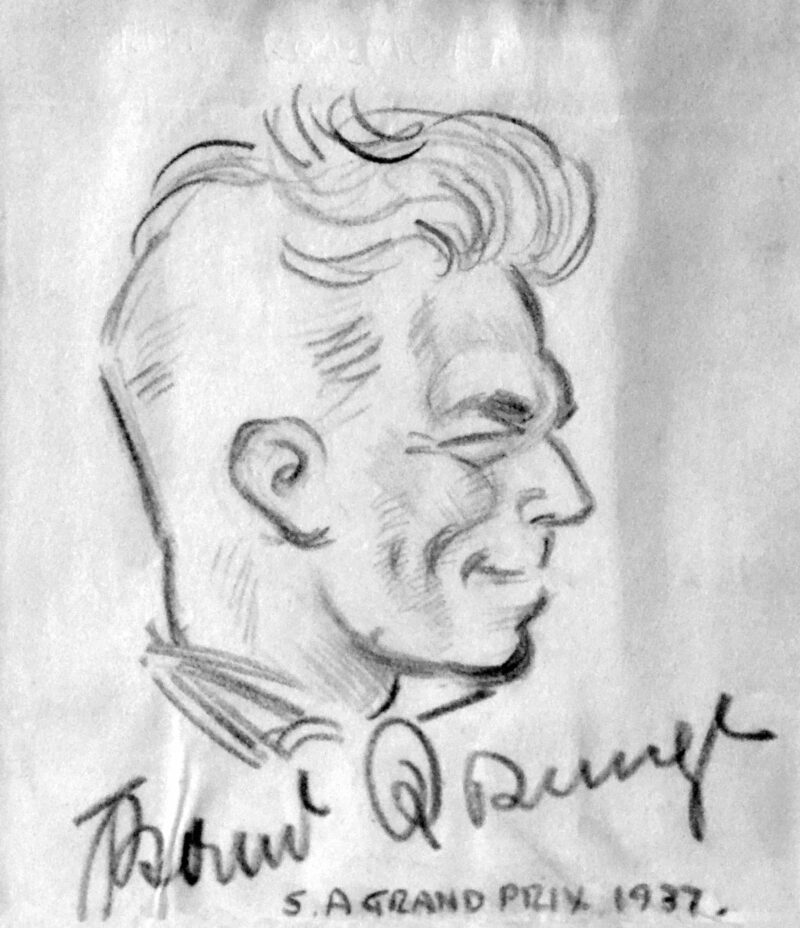

At the time of Auto Union’s participation in the South African Grand Prix in 1937, a prominent local cartoonist and illustrator named Jock Leyden did a pencil sketch of Rosemeyer, which he had the driver sign and subsequently gave to Graham Walker, Murray’s celebrated father. Now, nearly half a century on, it was coming to me, and nothing in my collection of memorabilia stands higher in my affections.

While there are exceptions to the rule, it is a quirk of most racing drivers – as surprising as it is regrettable – that they have little interest in the history of their own sport, but something about Bernd Rosemeyer seems to intrigue people. I remember Derek Warwick, for example, saying he had read the piece and wanted to know more. And at the German Grand Prix in 1980 Gilles Villeneuve told me that ‘an old guy in the hotel’ had said he put him in mind of Rosemeyer, and did that make sense to me?

Of course it did. So much of Villeneuve was reminiscent of Rosemeyer, and later I had similar thoughts of Stefan Bellof. All were freakishly quick, with talent to throw away – and all were abnormally brave. By Rudolf Caracciola’s account, “Bernd did not know fear, and sometimes that is not good. You had to know where the real danger lay and we actually feared for his life in every race. Somehow I didn’t think that a long life was in the cards for him.”

I will admit to having had similar thoughts about Villeneuve, and although I thought Bellof destined to be Germany’s first world champion, he, too, was clearly a man more likely than most to go out on his shield.

“It appealed that Rosemeyer was never part of the triumphal Mercedes-Benz machine”

“The Old Man,” said Gilles, “told me I reminded him of Nuvolari…” If I could see that, so could I understand the man who had compared him with Rosemeyer. And I told him some more about this iconic figure, mentioning that every year, en route to Hockenheim, I would pull off at that point on the Frankfurt-Darmstadt autobahn where Rosemeyer had perished in 1938. A memorial stands, I said, in the place where they found him. Villeneuve was aghast: “He died on an autobahn?” Yes: he had been making a record attempt.

I first learned of the memorial’s whereabouts – set back, at the end of a lay-by immediately beyond the Langen-Morfelden crossing – from Denis Jenkinson, who invariably paused there whenever he was in the vicinity. The young Jenks had been a fervent fan: “Nuvolari was everyone’s hero, but Rosemeyer was my favourite…”

A national hero at a time of a peak pursuit of power, Bernd Rosemeyer’s life would be short, but his legacy and legend continue

Getty Images

What originally appealed to me was that he was never part of the triumphal Mercedes-Benz machine. From the beginning of his brief career he was an Auto Union man, and I have always found these brutish and wayward cars more arresting than anything from the Three-Pointed Star. As well as that, Rosemeyer was invariably obliged to fight Mercedes alone.

Born in 1909, he initially raced motorcycles with success, but his sights were always on grand prix racing. Over the winter of 1934-35 Auto Union gave him a test, along with several other would-be drivers. Rosemeyer came out of it well, was offered a contract and in May 1935 made his debut at the ultra-fast Avus, of all places. It beggars belief that this was his first race in a car of any kind.

René Dreyfus, at the time driving Alfa Romeos for Scuderia Ferrari, was competing at Avus that weekend. From my frequent visits to New York, I came to know the gentlemanly Dreyfus well through the last 15 years of his life and was enraptured by his first-hand reminiscences of a time in racing so long gone. We would meet for dinner and the journalist in me yearned to take a tape recorder, but it would have been an intrusion on a social occasion with a man like René: instead I would hasten back to my hotel and scribble down everything I could remember.

“In those days,” he said, “Caracciola thought he was the best, and technically he was: certainly he was the most complete driver – but Nuvolari was undoubtedly the greatest. Tazio could do things with a car that no one else could do – although Varzi, until he destroyed himself, was almost his equal. He was the most precise driver I ever saw.”

And Rosemeyer? “If he had been given more time, who knows? Certainly no one – even Nuvolari – drove an Auto Union like Rosemeyer did. Some people said that because he never drove anything else it was easier for him to adapt to a rear-engined car – he had nothing to unlearn, if you like. That might have been true, but I would say he was faster than anyone…”

The signed artwork

Dreyfus remembered little of the race in which Rosemeyer made his debut. “Avus was a terrible circuit, very fast, but no real challenge, and everyone – except the Germans – hated it. I recall meeting Bernd for the first time and he caused a sensation by starting on the front row, but it was soon after that, at the Nürburgring, that he was really able to show what he had.”

So he was. In the Eifelrennen, on a wet-dry afternoon, Rosemeyer took the lead from Caracciola with three laps to go, and although he was ultimately repassed on the long straight immediately before the finish, he had given very serious notice of intent. In two races, he was on his way to becoming Auto Union’s mainstay.

This marked the beginning of a battle, sometimes very personal, between the two greatest German drivers of the time. “We did not,” said Caracciola, “give a second to each other. It was his wild, stormy, youth against the experience of an opponent 10 years older. He wanted to push me off my throne and I wanted to sit there a while longer…” As with Nuvolari and Varzi, though, the ferocious rivals would ultimately become friends. “Bernd was such a good-natured fellow,” said Dreyfus, “it was impossible to dislike him…”

Again, there are those resonances of Villeneuve and Bellof.

The final race of 1935 was the Czechoslovakian Grand Prix, and Rosemeyer – racing a car for the ninth time – scored his first victory. It was also here that he met Elly Beinhorn, then more celebrated than he, for she was Germany’s Amy Johnson, a flyer of great distinction, and in Brno to present one of her many lectures. On July 13 1936 – 13 was the lucky number of both – they were married and would travel to the races in her aeroplane.

Rosemeyer was the dominant driver of 1936, becoming European champion (then the equivalent of world champion) in only his second season as a grand prix driver. At the Nürburgring he won not only the German GP, but also the circuit’s traditional ‘second’ race, the Eifelrennen, in which as a rookie he had made such an impression the previous year.

If a single race defines Rosemeyer, and his place in racing legend, it is this one. Although it was mid-June, the Nordschleife was at its most treacherous. The fog lifted shortly before the start, but rain continued to beat down. For a couple of laps Caracciola led, but soon Nuvolari (Alfa Romeo) and Rosemeyer were past him and the race distilled to these two. They ran in tandem until lap seven, at which point thick fog descended again, whereupon the Auto Union took the lead and disappeared.

In her memoir of life with Bernd, Mein Mann, der Rennfahrer (My Husband, The Racing Driver), Elly Beinhorn Rosemeyer lists the lap times of both her husband and Nuvolari, and they make remarkable reading, being very similar until the fog came down – whereupon Nuvolari’s slowed dramatically and Rosemeyer’s hardly at all. In four laps of the 14-mile circuit, he pulled away by over two minutes, recording one of the most fabled victories in racing history.

Rosemeyer giving the salute after his dominant win in the 1936 Eifelrennen. He was no Nazi sympathiser though

Elly makes mention of Bernd’s extraordinary eyesight – way better than her own, which was in itself unusually good – and obviously that will have been no hindrance in conditions like these, but there is more to it than that. Imagine, if you will, what was involved in driving an unwieldy grand prix car, with 520 horsepower from its 6-litre V16 engine going to the road through skinny tyres, into the dead reckoning that was the Nürburgring that afternoon: Rosemeyer was touched by genius.

Here, on the face of it, was the personification of Hitler’s fair-haired Aryan hero, prepared to risk his life for the glory of Germany, the embodiment of youthful courage and strength. Grand prix racing was of immense importance to the country’s propaganda machine, and Hitler had his own man – one Adolf Hühnlein – at the races, always in uniform.

Recorded in Elly’s book is that Heinrich Himmler was so impressed with Bernd’s Nürburgring victory that he made him an Obersturmführer in the SS. This was considered a great honour at the time, and not, as Elly wrily noted, the sort of invitation you could refuse. With the award came a uniform, which, to the conspicuous disappointment of the Nazi hierarchy, Bernd resolutely refused to wear. Fortunately, as she points out, he was by now so much a national hero as to be effectively beyond sanction.

Today it is almost impossible to imagine the circumstances of GP racing 70 and 80 years ago. Dreyfus told me that he knew of no driver – save perhaps Manfred von Brauchitsch – who was a genuine Nazi sympathiser. “Certainly Rudi (Caracciola) was not, and nor was Bernd. But they all had to give the Nazi salute on the rostrum – even Dick Seaman, when he won at the Nürburgring in ’38…”

When the opportunity arose, though, the drivers delighted in puncturing Hühnlein’s authority. Before the German GP of 1937 they were lectured on the matter of morals: German men and women, went the stern instruction, do not kiss in public, so there must be no displays of affection before a race. Rosemeyer, it seems, had a quiet word with his colleagues, and as soon as Hühnlein and his cronies took their places in the stand, to a man the German drivers climbed from their cars, returned to the pits and – to loud approval from the crowd – positively seized their wives and girlfriends…

In December 1936 Rosemeyer drove an Auto Union in the South African Grand Prix, flying there in his wife’s Messerschmitt Taifun. What should also have been a holiday, though, was marred by news of his mother’s unexpected death. Soon after their return to Europe there was more family tragedy, for his younger brother Job was killed in a road accident.

“Racing is as essential to me as the air I breathe. I might be killed, but if I give up now it will be the end of life for me anyway”

Elly recounts that only once did his father ask Bernd to give up racing, which he said he could not do: “Racing is as essential to me as the air I breathe. I know I might be killed, but if I give up now it will be the end of life for me anyway. But I promise you this: if ever I feel nervous about racing, I will never get in a car again…”

If the 1936 season had been one of great success for Auto Union, the team had a more difficult time of it the following year, for by now Mercedes had introduced the iconic W125 and this indisputably was the car to have. If Caracciola regained the European championship, though, Rosemeyer still had his moments, winning the Eifelrennen again, as well as the Coppa Acerbo at Pescara and the Vanderbilt Cup on Long Island. There was also sadness, however: in the German Grand Prix Ernst von Delius, Auto Union’s junior driver and Bernd’s close friend, was killed in an accident with Seaman’s Mercedes.

In the autumn came the inaugural Donington GP, which brought the German teams to England for the first time. Rosemeyer was anything but enthusiastic about taking part, for he felt Auto Union had little chance against Mercedes, but in the event a typically brilliant drive brought victory after a long battle with von Brauchitsch. It would be his last.

Rosemeyer (left) with wife Elly Beinhorn and Manfred von Brauchitsch

Getty Images

Soon afterwards came the Rekordwoche – a week of record attempts to be staged on the Frankfurt-Darmstadt autobahn. Earlier in the year, when the stretch was closed to allow Goldie Gardner to go for class records in his MG, Auto Union took the opportunity to run a streamlined car for Rosemeyer.

All these years on, the circumstances take a little believing. For one thing, no autobahn is completely straight, and there were gentle curves in this one. For another, only one side of it was closed, with normal traffic proceeding along the other. For another yet, at the end of the run a knee-high barrier had been placed across the road, so as to divert traffic coming from Darmstadt into the lanes still open…

When Rosemeyer made his first run – supposedly only a warm-up – he not only went faster than expected, but also forgot about the barrier. When officials realised he wasn’t going to stop in time they hastily removed it, which was just as well for he went by them at about 175mph – and now found himself proceeding towards Darmstadt with normal traffic coming towards him!

Rosemeyer himself was unconcerned: “They could see me – I could see them…” Indeed he seems to have found the episode amusing; on reaching Darmstadt, he had space enough to turn the car around and calmly drove back again, remembering en route to thank those who had moved the barrier for him…

In the course of the day, Bernd set a number of Class B records, including 242.09mph for the mile and – astonishingly – 233.89mph for 10 miles! This last was achieved over a stretch of 14 miles, allowing for flying start and slowing down, and the strain of holding a car at that speed on a two-lane road, punctuated by bridges, can scarcely be imagined.

Afterwards his wife asked how it had been. “Crazy!” Rosemeyer said. “Especially in the 10-mile run. When you go under a bridge, for a split second the noise of the engine completely disappears – then returns like a thunderclap when you are through…”

Porsche leans in to speak to Rosemeyer

Getty Images

Bernd was disappointed, however, at being unable to break the 400kph (250mph) barrier, coming up only slightly short on his fastest run. “Just think of it – to be the first man to exceed 400 on an ordinary road…”

This he duly achieved during Rekordwoche in October. In what was very much a head-to-head between Auto Union and Mercedes, it was Rosemeyer versus Caracciola, the two greatest German drivers of the day – and this time both sides of the autobahn were closed.

“Bernd found himself at 175mph heading to Darmstadt, with normal traffic coming towards him”

Mercedes might have had the better of the grand prix season, but Auto Union’s streamliner (as had been raced at the flat-out Avus, where Bernd had lapped at a numbing 176mph) had a clear edge here, Caracciola not surprisingly disturbed by his Mercedes’ front-end lift at extreme speeds.

For Rosemeyer, who had set many new records, it was a week of complete triumph, although he had been disturbed by one long run, which he finished in a state of semi-consciousness, the probable consequence of exhaust fumes in the cockpit.

Now, at last, the season was over, and within a few days the Rosemeyers’ son – also named Bernd – was born. Ahead was apparently a long winter of rest with his family before the new father had to think about driving again, but at the start of January news emerged that Daimler-Benz, stung by what had happened in Record Week, was not prepared to wait for the next one and had pulled strings to enable another series of record attempts shortly to be made.

Rosemeyer was none too impressed, his wife incensed. “This was unjust,” she wrote, “because there was an unwritten rule that if one German company held a record, another would not try immediately to beat it. But there were many injustices done to Auto Union at that time because the management was not on the best of terms with the Nazi government, and refused to give Hitler any of the company’s big cars for his demonstrations. If Auto Union had failed in the 1937 Rekordwoche, we would never have received permission to try again in January 1938…”

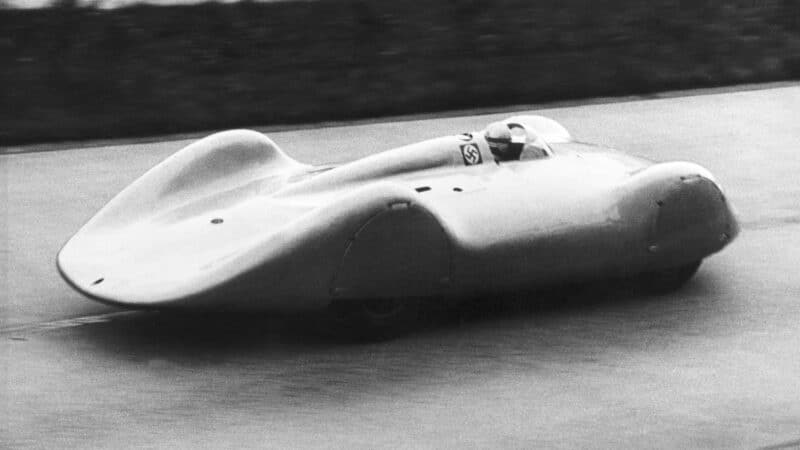

Be that as it may, the company felt obligated to compete. Mercedes had revamped the aerodynamics of its car, and now Auto Union hastily did the same. The car Rosemeyer would drive had all-enveloping bodywork that almost, like a precursor to the ‘skirts’ era in Formula 1, touched the ground.

Bernd arrived in Frankfurt on January 27, speaking light-heartedly of an emergency landing he had been obliged to make in bad weather the night before. The day was given over to an inspection of the autobahn course, and the next morning he arrived back there to learn that his record had been beaten.

Rosemeyer congratulated his rival, and in his memoirs Caracciola says that by this time the wind was picking up to a worrying degree, that he wanted to tell Rosemeyer to forget about running that day, but for some reason felt he should not interfere.

The Auto Union streamliner was designed by Ferdinand Porsche to take on, and beat, Mercedes, but the battle would end in tragedy.

Looking at it now, the whole thing seems insane. Here were two great grand prix drivers, blasting down a two-lane road at speeds not far from 300mph in wintry conditions. Why did it so matter which team held the record? One thinks of Eugenio Castellotti, killed at Modena in 1957, obeying the dictat of Enzo Ferrari that – for the honour of the company – he regain the circuit lap record from Maserati’s Jean Behra.

As it was, Rosemeyer put on his linen helmet, climbed into his car, made a first run, then the return in the opposite direction. When he came back he was pleased to learn of his speed, for he had not been flat out and had recorded 268mph, compared with Caracciola’s 270. He did, though, mention that there was quite a cross wind at the Morfelden junction. Shortly before midday the Auto Union accelerated away once more, but never came back.

The wreckage was strewn over six hundred yards. It was estimated it had been travelling at 280mph as it approached the Morfelden crossing, where it nudged the grass on the central reservation, then lost control, somersaulted and disintegrated. The cause of the accident was later ascribed to a freak gust, and this might have been crucial, but many believed the flimsy aerodynamic bodywork simply broke up, putting the car beyond the control even of a Rosemeyer. His body was found at the edge of the forest, where the memorial now stands, always with freshly cut flowers around it. He was 28 when he died, and had raced cars for only three years, fewer even than Villeneuve or Bellof. Meteors, as Dreyfus said, burn brightly but briefly.