Dick Seaman: Triumphs and Controversy in Pre-War Racing

One of Germany’s most successful pre-war drivers, Englishman Dick Seaman was a man caught on the wrong side of history. Richard Williams looks at his story, the uneasy relationship with Nazi leaders, and whether or not his reputation should be salvaged

Taken from Motor Sport, April 2020

At the end of a bright spring day at Monza, the timing sheets told the story. For Alfred Neubauer, studying the meticulously compiled chart headed Nachwuchsfahrer Ausbildung (New Driver Training), there was only one conclusion. The Mercedes-Benz team manager had summoned five young men to the test, and brought a pair of obsolete W25 grand prix cars down from Stuttgart for them to drive. Three were Germans: Heinz Brendel, Walter Bäumer and Heinz-Hugo Hartmann. One – Christian Kautz, an Oxford graduate – was Swiss. The fifth candidate was a 24-year-old Englishman whose promise had been evident over the preceding two seasons as he drove first an ERA and then a 10-year-old Delage to victory in some half a dozen important continental races.

Seaman won at Donington with Reusch’s Alfa 308C.

LAT

In MG at 1935 TT

Getty Images

The quintet had been winnowed from an original batch of 29 hopefuls, assembled for a preliminary test at the Nürburgring five months earlier – a motley bunch, including Daimler-Benz showroom salesmen and mechanics. They were sent out first in sports cars, with the instruction to lap slowly but consistently. Not all obeyed; one of them, a 21-year-old company delivery driver named Hermann Schmitz, went off and was killed. The fastest 14 were then sent out in W25s, again instructed not to overdo it. Five of them later received letters asking them to report for a second test in March.

Seaman takes his W154 round La Source, during the fatal 1939 Belgian GP

Daimler AG

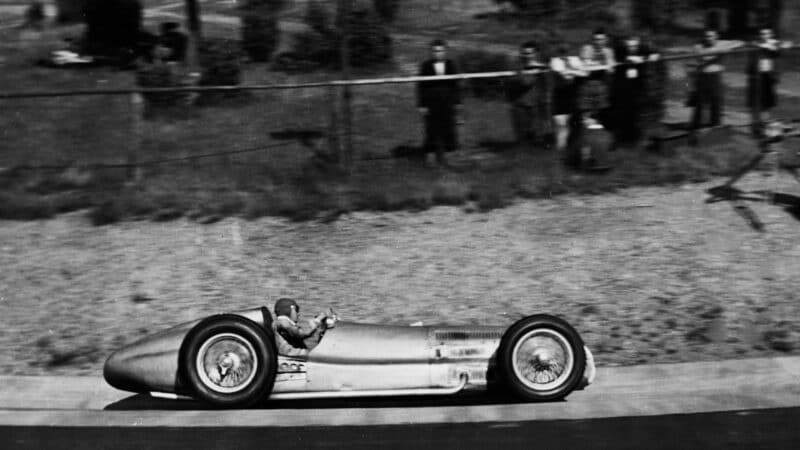

It was Dick Seaman, clad in all-black overalls and wind-helmet, who was the first to go out on to the Monza track in a 5.6-litre car producing three times the horsepower of his voiturettes – almost 600bhp – in a chassis of similar weight. For an ace familiar with the car and the circuit, three minutes flat would have been a good time. Seaman’s out lap was 3min 34sec, his first flying lap 3:15. Then he started to bring it down: 3:13, 3:12, 3:07, 3:06, 3:05, 3:05. His speed and consistency were thrown into higher relief when compared with the best efforts of the other four: 3:24 for Brendel, 3:20 for Bäumer and Hartmann, 3:19 for Kautz. The response from Neubauer was to send Seaman out again, this time in the second car. The result was the same: six flying laps, three of them in 3:05.

It had been an expensive exercise, and there had also been a fatality. “Our sole consolation,” Neubauer wrote in his autobiography, “was that we had found one driver of world class: Dick Seaman.”

Soon afterwards, Seaman and Kautz received offers to join the team as reserves to the three front-line drivers: Rudolf Caracciola, Manfred von Brauchitsch and Hermann Lang. As non-Germans, the new men required the approval of Adolf Hitler, whose government was subsidising the two teams – Mercedes and Auto Union –with the aim of dominating grand prix racing. The project was part of Hitler’s ‘motorisation’ scheme, which included the building of a network of autobahns and the creation of an affordable People’s Car.

“We had found one driver of world class: Dick Seaman”

The offer made to Seaman was a salary of 1000 Reichsmarks a month – just under £1000 a year in 1937, or about £65,000 today – plus prize money and bonuses which would quadruple his earnings for the year. The catch would be that, under Hitler’s restrictive currency regulations, the money could not be taken out of Germany. Seaman quickly decided to find a temporary home, selecting a villa on the shore of the Starnbergersee, a large lake 150 miles south-east of Stuttgart. He could call on the interest from the two trust funds set up by his late father, whose will stipulated that, thanks to reservations over Dick’s propensity for spending money on racing cars, the young man would have to wait until his 27th birthday for his full, and considerable, inheritance.

After a catastrophic 1936, in which Auto Union had won six of the season’s big races to its two, Mercedes urgently needed to restore its fortunes. At Untertürkheim the 380-strong staff of the racing team were working under Rudolf Uhlenhaut’s supervision to build the new W125, whose chassis, featuring stiffer tubes and softer suspension, represented a major change of design philosophy.

Though old, Seaman’s Delage brought success

Getty Images

Victory in the 1938 German GP put Dick Seaman in the Nazi spotlight for evermore, even if his salute lacked enthusiasm on the podium

Neubauer was also thinking about the men who would drive these new cars. The 36-year-old Caracciola, dethroned as European champion by Auto Union’s Bernd Rosemeyer, would be staying. So would Lang, aged 27, a local man promoted from the ranks of the mechanics. The volatile Manfred von Brauchitsch had been involved in a drunken scuffle in a hotel bar with Baldur von Schirach, the head of the Hitler Youth movement, but the 31-year-old had an Uncle Wilhelm whose friendship with Adolf Hitler was about to result in promotion to the rank of commander-in-chief of the German army, and eventually he was given a new contract.

Face to face with Hitler at the Berlin Motor Show

Getty Images

A generational rift within the team was already starting to open. Caracciola and von Brauchitsch did not consider Lang – as recently as 1935 the chief mechanic on Luigi Fagioli’s car – to be their social equal. A famous story had them entering the fashionable Roxy bar in Berlin, where von Brauchitsch gave their order to a waiter: “A bottle of champagne for Herr Caracciola and myself – and a beer for Lang…” When the ex-mechanic started winning races, kicking off the 1937 season with victories in the Tripoli and Avus grands prix, their disdain began to take on a darker hue.

Seaman’s family background and his education at Rugby School and Trinity College, Cambridge meant that he was every bit the social equal of Caracciola, a hotel-keeper’s son, and von Brauchitsch. But he himself was no snob. Much of his childhood had been spent in the stables and garages of the family’s homes in London and the country, in the company of chauffeurs and estate workers. One of those garages, in a mews beside their house near Hyde Park, became the headquarters of his racing team, run by former Alfa Romeo man Giulio Ramponi who had cured ERA’s unreliability and rejuvenated the ageing Delage, helped by two other fine mechanics, Lofty England and Jock Finlayson. So he was equally at ease in the company of Lang, a man of humble origins. And while admiring Caracciola’s virtuosity and finding amusement in von Brauchitsch’s displays of temperament, it was with Lang that Dick struck up the closest friendship.

With Prince Bira and Count Trossi at Crystal Palace, 1937

Getty Images

With his mother Lilian

Before his German had become reasonably fluent, the two young drivers could hold conversations through Uhlenhaut, who had been born in London and appreciated the younger men’s keenness to provide the sort of technical feedback that had never been forthcoming from their senior team-mates.

Seaman also had other values to the team. Some believed that Hitler had approved the hiring of an Englishman as part of a plan to pursue a tacit agreement with the British government. In the event of war, while Germany controlled the battle on land and in the air while overrunning continental Europe, Britain could maintain its historic command of the seas while remaining aloof from the conflict. A British driver in one of the all-conquering German grand prix machines would be a useful token of friendship.

“He was incapable of matching the stiff-armed Nazi salutes”

Dick had made three starts for the team, finishing seventh in Tripoli and fifth at Avus and retiring from the Eifelrennen, when Neubauer announced that he would be travelling with them to the United States that July. While half the team stayed in Europe for the Belgian Grand Prix, the other half would head to the Vanderbilt Cup. Neubauer and Uhlenhaut would be on the voyage, along with Caracciola, Mercedes’ greatest star, and Seaman, who would be able to talk to American journalists in their own language. The Auto Union team – including Rosemeyer and Dr Ferdinand Porsche – were also on the SS Bremen, as was Bodo Lafferentz, the head of the Kraft durch Freude (Strength through Joy) movement, and Jakob Werlin, a Munich car dealer who had become a Daimler-Benz director after selling Hitler his first Mercedes. Accompanying them was a film crew, tasked with making a propaganda film from this invasion of the New World.

Rosemeyer won the race for Auto Union, while Dick’s second-place finish, following Caracciola’s retirement, salvaged a little of Mercedes’ pride in front of 80,000 American spectators at the Roosevelt Raceway on Long Island. After a night unwinding in the clubs of Harlem with a Cambridge friend who was working on Wall Street, Seaman set out on the return journey to Bremerhaven, having noted the cartoons in the New York papers poking fun at the meticulous preparation of the German teams. On disembarking, they were immediately ushered into a celebratory reception hosted by Hitler’s sports director, Korpsführer Adolf Hühnlein.

1938: Seaman rounds Donington’s hairpin en route to third place.

Getty Images

The team, from left: von Brauchitsch, Neubauer, Seaman, Lang, Caracciola

Getty Images

Dick’s first season was studded with crashes as he got to grips with the machinery: fracturing his knee-cap at Monza in a test session; wrecking a car but emerging unscathed after a front brake locked during practice for the Coppa Acerbo at Pescara; and smashing his face badly enough to need plastic surgery in a Nürburgring crash that killed Auto Union’s Ernst von Delius. Only the first incident was his fault, and Neubauer told him not to worry because all their drivers had endured similar experiences on first exposure to the cars’ sheer power.

Shortly after retiring from the final race of the season, at Donington Park, he was summoned back to Germany to greet a special visitor to the Mercedes factory. This was the Duke of Windsor, the former Edward VIII, who had abdicated the British throne less than a year earlier and gone into exile in Paris. Now he and his new wife, the former Mrs Wallis Simpson, were touring Germany, taking tea with Hermann Göring, dining with Josef and Magda Goebbels, and being shown around a mine, a school, the Krupp factory in Essen where U-boats were being built, a Hitler Youth camp and an SS parade. The penultimate item on the schedule was a visit to Untertürkheim. The Duchess stayed in their Stuttgart hotel while the Duke was taken to the Mercedes factory, where Dick stood in the receiving line and helped show him around, answering questions about motor racing and life in Germany over cocktails. The following day the Duke spent an hour and a half with the Führer at his Alpine redoubt in Berchtesgaden, while the Duchess had tea with Rudolf Hess.

With over 600bhp the Mercedes was fearsome

Getty Images

By the time Seaman himself shook hands with Hitler a year later, before the 1939 Berlin Motor Show, his opinion of Germany had changed. Sharing a common view among the English upper middle class, his initial approval of the National Socialist government had been based on a visible upsurge in the nation’s morale. By comparison with Britain’s politicians, Hitler seemed a man who could get things done. Living on the peaceful shores of a lake, Dick took a while to recognise what was really going on. By the time his tumultuous win in the 1938 German Grand Prix made him the first British driver to win a grande épreuve since the hero of his schooldays, Henry Segrave, in 1923, he was incapable of matching the stiff-armed Nazi salutes that surrounded him on the victory podium. His reluctant effort was more the gesture of a man flagging down a No38 bus outside the Ritz.

The start of the 1938 Swiss GP at Bern. Seaman and Caracciola went head-to-head.

Relationships inside the team had deteriorated, with Seaman now feeling that he was being lumped in with Lang as a victim of the resentment aimed at the young upstarts by Caracciola and von Brauchitsch. He was also dissatisfied with Mercedes’ refusal to give him regular starts, and had written to the chairman, Dr Wilhelm Kissel, receiving an emollient reply and the offer of a personal meeting to clear the air. “I am firmly of the opinion,” Dr Kissel wrote, “that you will race for us not only now or temporarily, but that you should feel bound to the company and us here for all time, just like the rest of the drivers, such as Herr Caracciola.” Now, too, he was a married man, having wed Erica Popp, the 18-year-old daughter of the founder and chairman of BMW, to the dismay of his mother, who – after many arguments – had intended to cut him off from his inheritance if he insisted on marrying a German girl.

In Berlin, since their cars for the coming season were still being built, four old W125s were polished up and parked outside the Reich Chancellery, the drivers standing alongside in full race kit while Hitler greeted them individually. The engines were started and they roared past the assembled Nazi hierarchy before setting off along the dead-straight boulevard through the Tiergarten towards the exhibition halls, where, in a ceremony that Dick observed was worthy of Cecil B DeMille, Hitler gave his annual speech announcing progress on all fronts in the motorisation project.

“He would never have the chance to show which side he was really on”

Four months later Seaman would be killed while leading the Belgian GP in heavy rain at Spa, trapped unconscious in his car and suffering burns from which he died in a local hospital that night. Five days later Neubauer, Caracciola, von Brauchitsch and Lang arrived in London for the funeral at a church close to the Seamans’ London home, followed by a burial ceremony in Putney Vale cemetery.

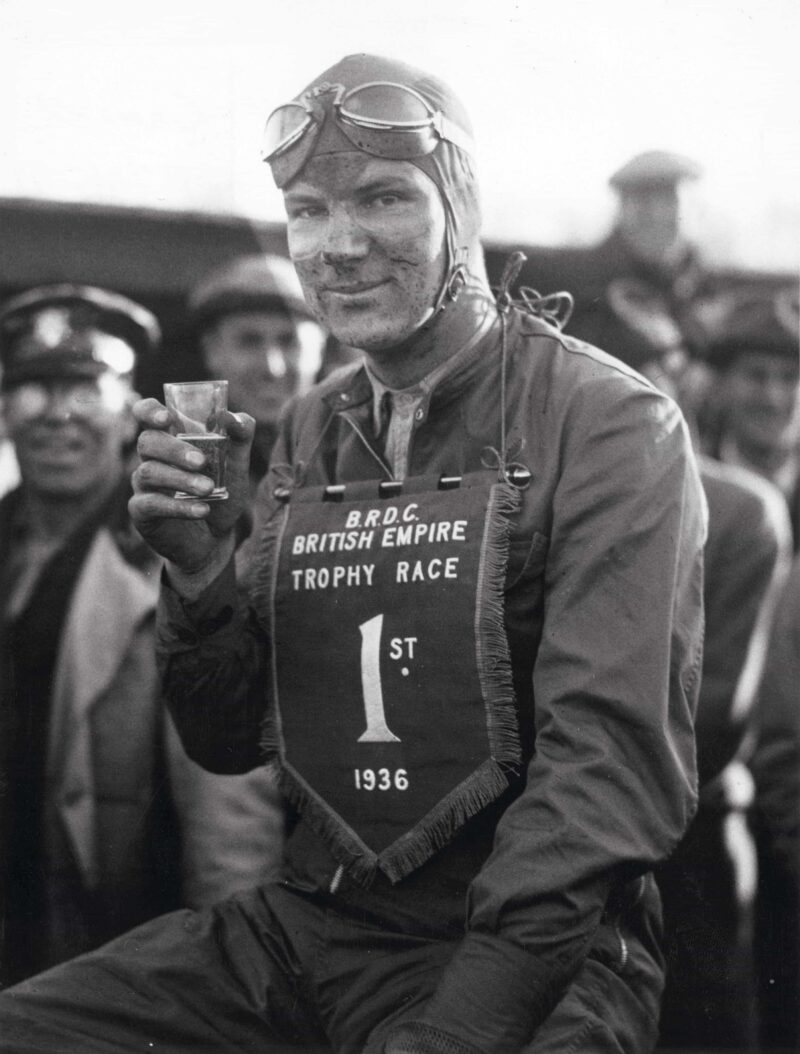

Victory in the British Empire Trophy at Donington Park in 1936, taken in a Maserati

Getty Images

In his final weeks, as he and Erica were settling into their new home – a chalet near Garmisch bought for them by his father in law – he reacted to the rapidly worsening international situation by asking Earl Howe, the president of the British Racing Drivers’ Club and a wise older head, whether he thought it was time to come home. Howe’s advice, having consulted political and military contacts, was to stick it out until the situation became intolerable. But Dick and Erica had been preparing for a quick exit, ready to load their bags and their two cocker spaniels, Whisky and Soda, into his old Ford V8, not his company-issue Mercedes.

In reality it was the Ford that would be left behind in Germany, disappearing in the chaos of war, along with the reputation of a young man who would never have the chance to explain, or to show by his deeds, which side he was really on.