How John Surtees Accidentally Became a Formula 1 Constructor

Taken from Motor Sport, November 2003 John Surtees was always destined to become a constructor. At least that’s how it appeared from the outside. For he absolutely knew his own mind…

I have spent the last few years travelling the world and driving as many Ferrari Sports-racers as I could. At the end, I was left with only one possible conclusion: That these, not F1, were the cars that created the legend.

Formula 1 is the sport’s ultimate showcase. And Ferrari has been its 50-year constant, its pivot, its most famous team and, by association, the most famous marque in the world. But F1 is not what made Ferrari great. That role fell to its super-successful sports-racers and GTs of the 1950s and ’60s. Everything since has been the icing on an already tasty cake. Henry Ford knew it 30-plus years ago, which is why he wooed Enzo so mercilessly. But on the verge of buckling to the weight of the Yankee dollar, II Commendatore had second thoughts, a snub that triggered the Blue Oval’s scorched-earth Le Mans assault in the ’60s. And before you mention the DFV’s Fl domination, remember that Keith Duckworth’s masterpiece was a £100,000 drop in Detroit’s vast reserve; the GT budget was akin to that of a third-world country’s gross national product.

Jaguar had shown the way, with five Le Mans wins in the ’50s helping it pierce American consciousness and create a global presence. A key man in Ferrari’s worldwide growth, therefore, was Luigi Chinetti, Maranello’s American importer and an arch racing enthusiast. He scored the marque’s first Le Mans win in 1949, and urged Enzo to take the event, and the category, more seriously. While the boss viewed building road cars merely as a way of funding his racing activities, Chinetti saw that there was money to be made here, money for growth rather than simply existence. His victorious 166MM was a 2-litre V12, which he was sure was insufficient to win the race again and/or impress America.

Alain de Cadenet

Getty Images

Two years later, basically the same car finished fifth — except this version was called a 340 (4.1-litre) America. There’s a clue there. Two years later still, the brutal 4.9-litre 375 Plus of José Froilán González and Maurice Trintignant bludgeoned its way to Ferrari’s second Le Mans victory. And across The Pond, Ferraris were making hay in the American racing scene. It had begun. As had the following step: the Berlinettas, the ‘little sedans’, the street link. What follows is my experience of the best of Ferrari’s street-racing Berlinettas…

That Ferrari got it so spot-on so early in its history is extremely impressive. It’s not as if the brand wasn’t ambitious: V12 and a five-speed gearbox. And it’s not as if it was a box of tricks: it won Le Mans, the Mille Miglia and Targa Florio. Tough stuff. Under that lovely Barchetta body lies a very rugged car.

Unsurprisingly, this early model possesses the most vintage feel of all the Ferraris in this article: a crash gearbox that takes a bit of finessing and primitive drum brakes. But it’s so willing that you can forgive it any shortcomings.

It doesn’t have masses of power (140bhp) but that means you can use all of it all of the time. It’s surprisingly torquey too, making it a very useable car that always does its best for you. You can’t ask for more.

I have a lot of respect for the guys who tackled the Carrera Panamericana. Just a few miles in this Vignale Berlinetta had my head clanging: the closed body might keep the Mexican dust out, but it also keeps the smells, vapours and deafening noise in.

Driving this car on loose-surface roads like those you’d find on the Carrera, it feels positive and controllable over the bumps, despite a live axle/leaf-spring rear end. Its engine (a 3-litre fitted by the factory in place of the original 2.5) pulls like the proverbial and fifth is an over-drive — handy for those long straights.

The general impression, though, is that it’s a bit gothic; you sit on it, not in it. We’re at the beginning of the GT line and, clearly, there’s lots of R&D still to come.

Eugenio Castellotti at speed in the Dunlop Curve with his Ferrari 121LM at the 1955 Le Mans 24 Hours

Getty Images

The six- and four-cylinder racers don’t have the cachet of the V12s, which means this is one of the great ‘hidden’ Ferraris. Its combination of a 4.4-litre straight-six and lightweight body (verging on two-seater F1) makes it a startling performer: with a good compromise between four-cylinder torque and V12 revs, this unit gives around 350bhp of grunt.

But there’s so much more to this car: the driving position is excellent, the shockers work well, the brakes are very impressive and the five-speed transaxle, though slower than some, has a nice, engineered feel to it. Had the works bolted it together as well as this is now, it might have been the car to beat; Castenotti was ahead of Moss in the 1955 Mille Miglia until his tyres blew.

Luigi Musso in his Ferrari 860 Monza at the 12 Hours of Sebring in 1956

Getty Images

Phenomenal torque is the key here. This 3.5-litre four-cylinder was in its element on the twisting mountain roads above Monterey, bursting out of uphill corners.

There’s no need to row it along on the gearbox (a five-speed transaxle — early cars had a four) and it’s a lot more relaxing to drive for it.

Power tails off early, at 6500rpm, so it would not be at its best on the faster, sweeping, circuits – especially as it had a reputation of being an understeerer.

This shorter engine should have been easier to package, but Ferrari probably didn’t get the best out of the benefits and, in the end, missed out on a bit of weight over the front axle.

It might have been cured had Ferrari not been building fours, sixes and V12s at the time.

The Ferrari team at Le Mans in 1957, with Mike Hawthorn, Peter Collins and Louise Collins sitting on the pit wall, and Luigi Musso standing behind. While the cars looked fantastic, the race would be a Jaguar whitewash, with D-types filling the first four places

Getty Images

Typical Ferrari: take a 290MM chassis, a 250GT engine and a TR body and make it work — brilliantly. Enzo was not averse to sticking his head in the sand, but at times he showed great foresight. His entry for the new 3-litre sports car championship was simple, light, powerful enough, and, perhaps just as importantly, beautiful.

This early version has drum brakes, an all-synchro four-speed gearbox, a live rear axle and ‘Pontoon’ body — all to be replaced in future years. It’s also got the six-carb unit, albeit with the earlier hairpin valve springs and perhaps only 275bhp. Most of all, it’s got the ability to bring out the best in a driver — lovely chassis, instant throttle response and superb steering. Ferrari has come a long way and is approaching its sports car zenith.

Cliff Allison settles into the cockpit of the Ferrari TR/59 he is to share with Dan Gurney during the Nürburgring 1000km in June 1959. This was a strong lineup of Ferraris, but they were unable to do anything against Stirling Moss in the Aston Martin DBR1. Right behind is the number 4 of Phil Hill/Olivier Gendebien, which would finish second ahead of the number 3 of Tony Brooks/Jean Behra. Allison/Gurney would be fifth

Getty Images

Although still resisting the mid-engined revolution, Enzo made sure the absolute maximum was extracted from the front-engined format.

This car, the 1960 Frere car and Gendebien’s Le Mans winner, has a five-speed gearbox, disc brakes, and a de Dion rear end. It feels much tauter than its predecessor and has much better traction out of the corners.

This extra grip at the rear makes it an understeerer, some of which was dialled out by switching from Englebert to Dunlop tyres. Within the cockpit you feel much more a part of the car. And those improved ergonomics and aerodynamics mark the next step in the sportscar process. And just look at that glorious Fantuzzi-built body. It has his mark all over!

An alloy-bodied SWB with a 300bhp Testa Rossa engine makes for the best Ferrari road car. Ever. You can jump in it, fire it up and drive across the Continent. A big petrol tank, genuinely quick and with plenty of ground clearance.

A fantastic-looking car with a fabulous history. Perhaps the epitome of the GT theme. Light steering but with lots of feedback — not yet rack-and-pinion but as developed as recirculating ball got.

The four-speed ’box has a long throw but is delightful — like a big switch. The early disc brakes are surprisingly good, a firm feel through the pedal and no grabbing. You can really lean on this car.The Dunlops of the time were perfect for it: progressive, good in the dry, awesome in the wet. Just lovely.

Mid-engined at last. Rack and pinion, too. Much-improved discs, tight gearbox and a positive clutch. We’re getting there. But then there’s that familiar, torquey, willing 3-litre 250 V12 behind you, and a surprisingly soft, understeering, user-friendly feel.

Where the early mid-engined sports cars scored was on their improved traction; the other advantages lay untapped because the spaceframes of the period were not yet up to stiffer springs, nor were the tall-sidewall tyres. More importantly, the cars had to cosset their drivers over long distances and deal with bumpy surfaces.

The 250P’s record speaks for itself: it ushered Ferrari through its engine volte-face and triggered another period of domination.

This 1965 Ferrari 275 GTB Alloy ‘long nose’ sold for a total of €2.875m with Bonhams in 2019

Bonhams

The most pleasant, tasty-looking Ferrari road car ever built — especially this longnose version, with alloy body and right-hand drive.

This is Pininfarina at its very best. Its longer wheelbase makes it more relaxing to drive than the GTO, though its twin-cam (later quad-cam) 3.3-litre V12 has more than enough performance to keep you on your toes.

The five-speed transaxle is superb, too. But all this doesn’t make for a great racing car. Weight is the problem here. And the brakes. The ‘anchors’ are still lagging behind in the development stakes; the 275 needs four-pot calipers and vented discs, but has to make do with solid discs and two pots per corner.

It might’ve got them though, had it been intended as an out-and-out racer like the GTO was.

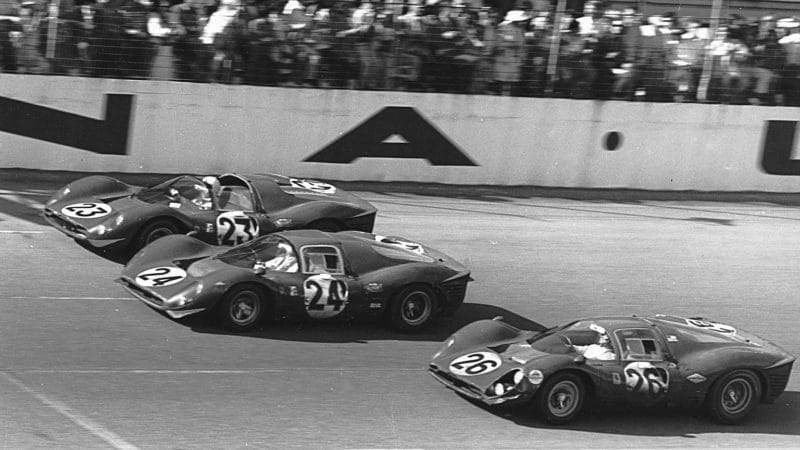

Ferraris dominated the 1967 Daytona 24 Hours. The No.23 330P4 of Lorenzo Bandini/Chris Amon won, followed by Mike Parkes/Ludovico Scarfiotti (No.24). The No.26 330P3/412P entered by Luigi Chinetti, was third, driven by Pedro RodrÍguez and Jean Guichet

Getty Images

When I started out racing, this was the car I craved. It doesn’t disappoint. Momo, Veglia, Campagnolo, Magneti Marelli — so evocative. And that’s before we fire it up. We have entered a different realm here: four-litre, 420bhp, quad-cam, three-valve head, fuel injection (for the works cars).

Once on the move, it feels much smaller than it actually is. A not-too-knobby gearshift on the right, pedals that lighten once under way.

Brakes are now Girling off-the-shelf items — still only two-pot, but not bad. Most Ferraris are set up to be neutral handling on a trailing throttle, and the P3 does just that — an attitude that can be easily controlled and easily changed. That curved screen causes distortion, but I could live with that!

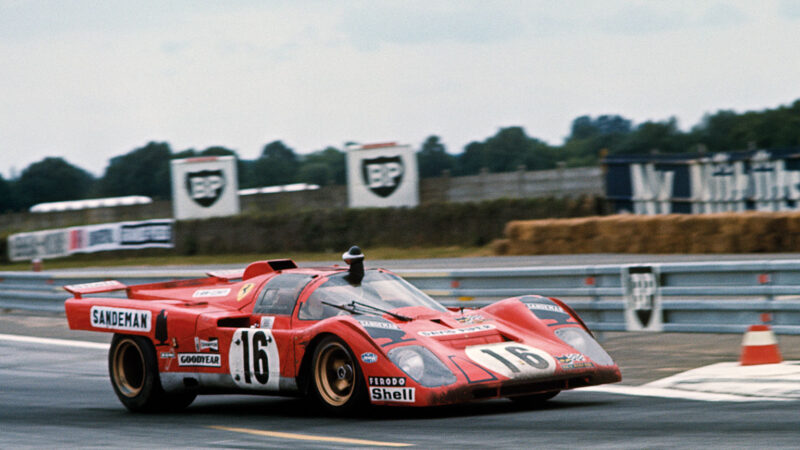

Chris Craft and David Weir’s 512M at the 1971 Le Mans 24 Hours

Getty Images

Comfortably the most powerful, fastest car I’d driven by 1971 (625bhp, 220mph), yet it proved one the most comfortable to drive. I raced one for the first time, at Le Mans, while blind in one eye and on one leg following a Targa Florio shunt. I was scared stiff, but within one lap the 512M had put me at my ease. So you can imagine how good it felt when my damaged eye chimed in during the night! The car was incredibly well behaved — sideways out of Arnage and the Ford Chicane, flat at 8200rpm through the Mulsanne Kink, and that was it.

All it lacked was the R&D Porsche put into its now-legendary 917. Remember how bad that was on its debut? It’s a shame Enzo was disenchanted with sports car racing at that time.

The 365 GTB/4 ‘Daytona’ was the last of Ferrari’s period road-derived racers, seen here during the 1972 Le Mans 24 Hours with Sam Posey at the wheel

Getty Images

I have got a soft spot for the Daytona. I picked one up from the factory in 1970 and drove it back to England, and it was just perfect for a trip like that.

People moaned it had heavy steering, but a few extra psi in the fronts eased that problem. And anyway, you could forgive it because of a superb, 4.4-litre 352bhp V12. But, like the 275GTB, this model did not star on the tracks. It still won the Le Mans GT category, of course. The car I drove here felt like a stripped-out road job and no more.

A few lightweight panels — the bonnet, the boot, the doors. Bigger discs and (finally!) some four-pot calipers, but it still took a lot of stopping. And there was very little development as Ferrari’s GT racing love affair was coming to an end.

As prototypes took over, Ferrari’s interest began to wain. But there would still be some flourishes, such as Jacky Ickx and Clay Regazzoni sharing this 312PB during the 1000km of Spa in 1972. They’d be second to the sister car of Arturo Merzario/Brian Redman

Getty Images

It’s hard to imagine something so far removed from the mighty 512 than the 312 — minimal, compact, nimble — but Ferrari was once again ahead of the game and got it spot-on. This two-seater F1 car feels so sharp, even on 30-year-old Firestones, and its flat-12 represents another quantum leap. The ‘Boxer’ is more willing than the DFV of the period (440bhp in sports car trim at 12,000rpm) but lacks a little in the torque department. Switch-like gearbox, brakes (vented discs) that at last match the performance, and it’s also stunningly beautiful. What a package!

Ferrari offered me one on the condition I wouldn’t race it, which is how Gordon Murray came to design for me a DFV version — but that’s a different story.

Does this car still possess the Ferrari mystique? Yes, but only just. Carbonfibre is fantastic, but it’s also very impersonal. For a driver used to a flexing, twisting spaceframe, a modern monocoque seems to alienate you from the driving experience. I also find that the revs a modern racing engine can pull is a little numbing.

These units lack soul, somehow. I will admit that the sequential shift was addictive, the thump in the back was impressive (in any gear) and the brakes were sensational. What really intrigued me, though, was that IMSA bent the rules to allow Ferrari to race one in the series, and that the 333 owners bought the cars ready-to-race.

It would seem that some things never really change. Thankfully.