Martin Brundle back in Group C Jaguar XJR-12

The look on Martin Brundle’s face the minute he walks into the garage at Silverstone is a picture. There’s an instant flicker of recognition. The same reaction as meeting an…

Whatever the 1923 Italian term was for, ‘On your bike, son,’ 25-year-old Enzo Ferrari surely uttered it as the carabiniere walked away empty-handed. The officer had arrived at Alfa Romeo’s Milan factory earlier that autumn day with legal papers that allowed him, on behalf of Fiat, to search the offices of Alfa’s new designer Vittorio Jano. He was looking for racing car blueprints that Jano might have ‘forgotten’ to leave at Fiat’s Lingotto factory in Turin, when he’d recently left their employ. When that search proved fruitless so it then moved to Jano’s house – and again nothing was found.

It was Ferrari who had tempted Jano into defecting from Fiat, the same Fiat that had told a desperate Enzo just four years earlier that it couldn’t afford to give jobs to every war veteran that walked into their offices off the street, letter of introduction from his commanding officer or no. Ferrari, his father and brother recently deceased, feeling totally alone and now apparently without prospects, later described how he had walked over the road to Valentino Park that day, brushed the snow off a bench there, sat down – and wept.

With the benefit of detachment and hindsight, it’s easy to see Fiat’s points, both in 1919 and ’23. At the cessation of the war there was rather more labour available than there was space in the factories, and it would have been difficult to know to what use to put a mule-shoer anyway. While in ’23 they had already been the victims of head-hunting, Fiat’s best technical brains – the men who had conceived the fabulous epoch-making series of grand prix cars that left the rest trailing in their dust – being poached with bags of gold.

The big names were the first to go: Vincenzo Bertarione and Walter Becchia to Sunbeam in late ’22. But now the second layer of brilliant but lesser-known talent: Luigi Bazzi, a friend of Ferrari’s, to Alfa a year later. Once ensconced at Alfa, Bazzi suggested that the guy they really needed was Fiat’s backroom technical manager, Jano. So it was that Ferrari set off to Turin on another vital errand for his employer Alfa, sucking the talent from the company that spurned him and directing it against them with targeted purpose. Fiat would not have even known the resentment it had triggered, nor how that was fuelling the depletion of its ranks.

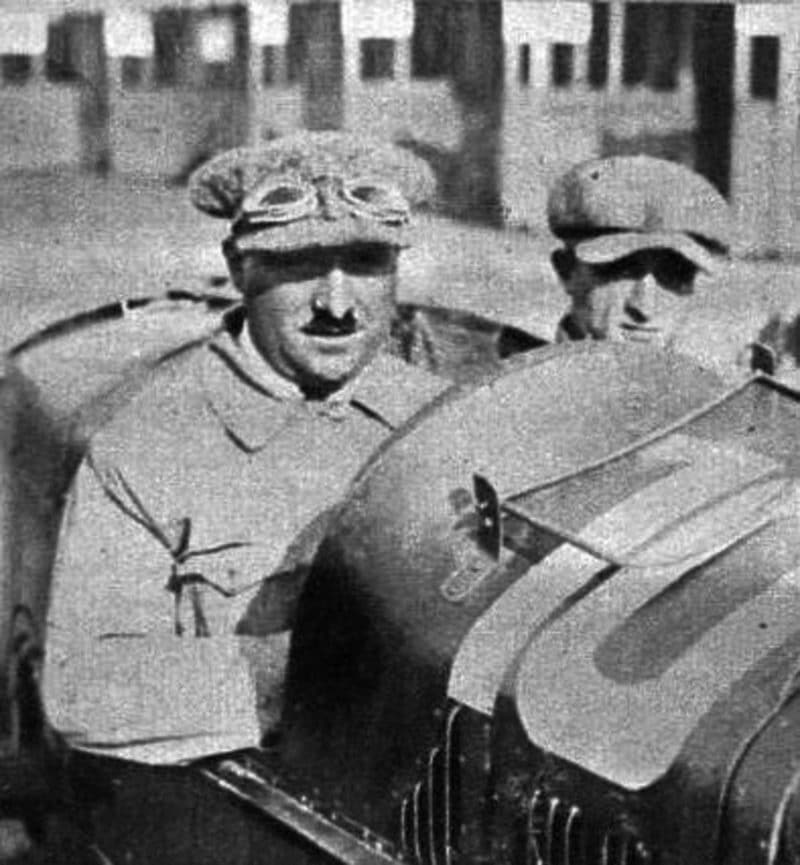

A young Enzo Ferrari (right) in the pits at Monza alongside Italian engineer and entrepreneur Nicola Romeo (middle) and engineer Giuseppe Morosi (left) in 1923

Getty Images

It wasn’t just the money that was tempting them; there was resentment within the ranks, too. That was down to what would now be called the poor people skills of Fiat’s brilliant but volatile technical director, Guido Fornaca, aka ‘The Duke of Lingotto’. He was the chief ally of company founder Gianni Agnelli and a shareholder in the business. A brilliant engineer, he had conceived many of the pre-war racing Fiats as well as several series of successful road cars. As head of the technical department, his patience for imperfection was thin. But people didn’t respond like machinery to his iron will. With the whiff of social foment in the post-war Italian air – Fiat’s factory had recently been the venue for a workers’ soviet, the dissidents barring both Agnelli and Fornaca from entering – those beneath the authoritarian Fornaca, their salaries a fraction of the shareholding income of their boss and dwarfed even by their peers elsewhere, set up their own quiet little rebellions and were all too ready to defect.

The ’23 French race had been a debacle for Fiat, the fastest cars by a massive margin – way faster even than the ‘green Fiats’, as the copycat Bertarione-designed Sunbeams were dubbed – but all three retired whilst leading. The Bertarione/Becchia Sunbeam triumphed, and if that didn’t provide irritation enough to Fiat, there was also the new Delage to bug them: the previous year its designer, Charles Planchon, had been observed blatantly photographing the Fiat’s engine. And even if the Delage’s V12 layout trumped Fiat for audacity, its detail revealed the heart of its inspiration lay in Turin; the same valve angles, same bore/stroke ratio, same crankcase architecture, it even had the same triple concentric valve springs!

So Fornaca’s mood was almost certainly poor even before his cars stopped. His frustration can easily be imagined; he’d built the most brilliant technical team of all time and now others simply plundered it. Not only plundered it – but now in Tours used that plunder to beat it! But only because Fiat had shot itself in the foot; it had lost not through insufficient performance, but sub-standard preparation. The supercharged racers had been tested on the smooth, clean surface of Monza – which was nothing like the dust-strewn public roads of Tours, pummeled to little more than farm tracks once the race cars had been let loose on it.

Before joining Alfa Romeo as a driver – and skilled talent poacher – Enzo Ferrari worked as a test driver for Milanese marque CMN, following his rejection by Fiat

Ferrari

In the aftermath, that very evening in Tours, Fornaca had ranted about the circumstances that had led the Fiat’s new-fangled superchargers to seize through ingestion of dust, throwing blame all around him. Bazzi, a proud man and a very able engineer, was not prepared to accept that, and the pair had a blazing, and very public, row.

When Bazzi had related the story to Ferrari, Enzo sensed his opportunity. “Come to Alfa, we are much smaller, more personal, good people, working on a grand prix car of our own, but we need someone with your experience.” This much was apparent a couple of months later at Monza where the company attempted to enter the grand prix arena. Ugo Sivocci – a close friend of Ferrari’s, the man who had thrown him a lifeline after Fiat had so glibly brushed him off – was killed testing the new Alfa there, Enzo cradling his dying friend as they took him to hospital.

Not long after crying on that park bench, Ferrari had befriended Sivocci, an ex-racing cyclist who then found Enzo a job at the small car company CMN at which he worked. Their efforts there had led to their recruitment by Alfa in 1920, as race drivers. But Enzo’s role quickly evolved from there, his wheeler-dealer talents and familiarity with Milan’s car racing milieu becoming increasingly valued by Alfa’s racing manager, Giorgio Rimini. The Alfa racing adventure gathered momentum, taking Ferrari and Sivocci along with it. But now this – an innocuous slide on a wet track, the slippery wet grass, the ditch beyond it, the roll, the crushing weight of the car…

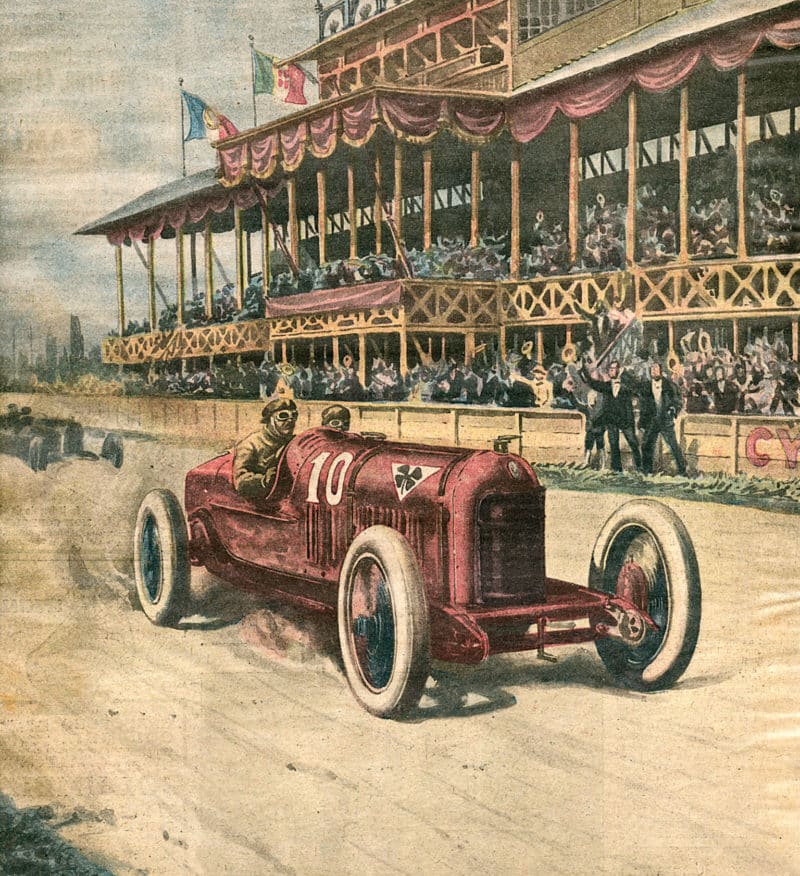

The XVIII Grand Prix de l’A.C.F took place at Lyon in August 1924

Alamy

But even before that catastrophe it was fairly apparent the new Alfa P1 was not made of the stuff to strike fear into Fiat’s heart. Bazzi looked around him, saw the limitations of the operation and knew that Jano was the man to lick it into shape – and so Fiat was plundered further, Enzo’s persuasive talents probably pushing against an open door, the deal signed off by Rimini, a glint in his eye, cigarette dangling from his mouth.

Ferrari was awe-struck by Jano’s work that winter: “No description could do credit to this extraordinary man and his fertile brain. With Jano, there came over to Alfa also other technical staff of less renown. Once in Milan, Jano took command of the situation, introduced a military-like discipline and in a few months succeeded in turning out the P2.”

But Jano’s creation, Alfa’s weapon for the 1924 season, bore a striking similarity to the Fiat, much more so even than the Sunbeams. Fiat’s lead driver Pietro Bordino first set eyes upon it at Lyon, venue for that year’s Grand Prix de l’ACF, the most prestigious race of the season. “Hey, if you need any parts for your new car, come see us,” he was reported to have told Jano, sarcastically.

Fiat was the establishment, the world’s greatest, most technologically advanced automotive giant. Its culture was one of learned, enlightened progress, its products the mechanical embodiment of intellectual rigour. Alfa Romeo was a small, regional manufacturer, not long since graduated from building Darracqs under licence, its competition arm little more than a racing shop. Enzo Ferrari was an operator, not a big company man. He hustled, sniffed opportunities and made something from them. Working for a corporation wouldn’t have been his thing; he would not have worked long under Fornaca, but under the chiding, mischievous but shrewd patronage of Rimini, who gave his protégé ever more responsibility in running the racing operation. As he evidently passed successive tests, Ferrari blossomed. Shrinking back from what would have been his grand prix debut as a driver at Lyon in a P2 was perhaps one of the shrewdest moves he ever made.

Enzo caught a train home that day, but what he had helped put in place set up the operators, the chancers, the copyists, to take on and beat Fiat through superior preparation – and the second successive humiliation was the final straw for Fiat. After Bordino fell out of his fight for the lead with Antonio Ascari’s Alfa because of a brake problem – for which ironically the team had no spares, despite Bordino’s earlier taunt – Fornaca howled again, raged against the imbeciles under his command. “Why had the cars been driven here, wearing them out before the race had even started? We already knew the folly of this from the Targa earlier in the year when Carlo Salamano had crashed down a ravine on the way to the race, damaging the car and breaking his arm! Why were there no spare brake parts? For such stupidity we are beaten by our inferiors, our copyists – again! We train all our people, gift them the greatest environment in the world in which to learn, and they betray us. Well if all racing is doing is advertising how brilliant our engineers are, a shop window for our rivals to buy from, then we stop. We stop now, and direct ourselves to more pressing matters.”

It was won by Giuseppe Campari driving an Alfa Romeo P2, copycat Fiat or not

Alamy

Alfa celebrated with the winner, Giuseppe Campari, the amateur opera singer no doubt let loose with his vocal apparatus, lubricated by vino. Alfa may have used a copycat design to triumph but it had utilised that tool more effectively, had prepared more thoroughly. Ascari had driven the car to victory in a minor Italian race, two months before – engineer Bazzi acting as his riding mechanic, listening to every little noise, observing the car’s every nuance – debugging the car before it mattered. Campari had put further racing miles on it a month later. At Lyon, Ascari – the only other driver who may have been as fast as the great Bordino – took on the leading Fiat, the pair slugging it out like a couple of heavyweights in the ring. Although that battle did for both cars, in Campari Alfa had a faster driver than any of those left in support of Bordino at Fiat once Felice Nazzaro had retired, also with brake failure. That would not have been the case had Salamano not still been incapacitated from that silly accident earlier in the year.

The big company resource of Fiat had been defeated by the sharp racing savvy of a small, independent-thinking group of racers. And it caused the corporation to leave racing. It was a theme that would be repeated many times in the sport’s history with many different players. In among it all on many of those occasions would be that great agitator of men, Enzo Ferrari. Now he had prospects, oh yes; he’d barely even started. That carabiniere receding into the distance was just one of many challenges he would see off.