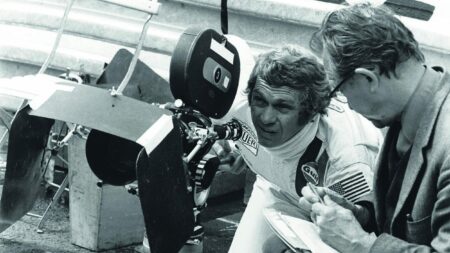

McQueen. One man and his movie

Sometimes you have an idea floating around in your head for days, weeks or even months, but in the case of documentary film Steve McQueen – The Man & Le…

Denis Jenkinson read the situation perfectly. In early 1962, as the dust settled following the ‘Palace Revolt’ in which a number of senior figures had left Maranello, Jenks wrote in Motor Sport that the upheaval was “not likely to have any effect, for after all, Enzo Ferrari has been running a racing team for many years”. In that time, he added, “there has been a long list of engineers coming and going… and yet Ferrari has gone on undisturbed, and it is my guess that he will continue in the same way”.

He did – for the most part. The Scuderia’s Formula 1 fortunes briefly slumped, but otherwise it was business as usual – which meant fighting on a number of fronts. When the 1962 250 GT Berlinetta – soon to become known to one and all as the GTO – was presented at Maranello that February, it stood alongside not only the latest grand prix car, but also the mid-engined 196 SP, 248 SP and 286 SP sports-racers. Whatever the discipline, Ferrari had all bases covered.

And therein lies one of the stories of the season. Sports car racing was having one of its occasional identity crises and the 1962 world championship would be fought out solely by GT cars – not a prospect that thrilled the organisers of the blue-riband races. They argued that no one wanted to see GT-only grids, and announced that they would therefore allow ‘experimental prototypes’ into their events.

A dream line-up of Ferrari sports racers at Maranello before the 1962 season

Revs Institute

The upshot was that championship rounds such as the Sebring 12 Hours, Targa Florio, Le Mans 24 Hours and Nürburgring 1000Kms were all won outright by sports-racing cars. GT machinery was often relegated to competing in a ‘race within a race’ – and to muddy the waters further, the championship itself was split into three divisions according to engine size. To quote Jenks again: “To win a GT championship outright is interesting; to win a third of the championship is absurd.”

But those were the conditions that prevailed, and even if the 1962 championship was missing the hillclimbs and criterium-style ‘rallies’ that would be added to the schedule in 1963, it wasn’t lacking in variety. It encompassed everything from the wide-open airfield at Sebring to the tortuous Circuito Piccolo delle Madonie for the Targa Florio, compact Goodwood to the epic Nordschleife – and, of course, the Le Mans 24 Hours.

250 GTO No19 finished second at Le Mans 1962, driven by Jean Guichet and Pierre Noblet

Getty Images

During 1961, hopes had been high in the British media that the new Jaguar E-type would take the fight to Ferrari, but a competition programme wasn’t a top priority at Browns Lane. In that respect, the contrast with Maranello was stark, Mauro Forghieri simply stating that “the factory was dedicated to the racing world”. There was no way that a half-hearted approach by the Scuderia’s rivals was going to be enough to knock it from its lofty perch – and so it proved.

Having not been ready in time for the opening round of the championship at Daytona, the GTO made its racing debut at the Sebring 12 Hours on March 24, chassis number 3387 GT being entrusted to the stellar driver pairing of Phil Hill and Olivier Gendebien. Hill was initially somewhat dismayed to be in “this damn coupé” but, as the assembled sports-racers struck trouble, he and Gendebien enjoyed a strong run to second overall behind the Ferrari 250 TRI/61 of Jo Bonnier and Lucien Bianchi.

There were more Ferraris than any other marque at Le Mans in ’62 – GTO No58 DNF

Getty Images

Former works Maserati driver Giorgio Scarlatti did the lion’s share of the driving as he and the car’s owner, Pietro Ferraro, finished fourth overall in 3451 GT at the Targa Florio, but the same pairing then failed to finish in the Nürburgring 1000Kms. So did the other GTO that had been entered – driven by Umberto Maglioli and Gotfrid Köchert – but fortunately the Short Wheelbase of Wolfgang Seidel and Peter Nöcker picked up the pieces by finishing fifth overall and maintaining Ferrari’s perfect score in the championship.

Graham Hill stirred British souls by briefly leading the Le Mans 24 Hours in the Project 212 Aston, but Ferrari took an iron grip. While Gendebien and Phil Hill romped to victory in the works 330 TRI/LM, Jean Guichet took his GTO (3705 GT) to second overall with Pierre Noblet, and the Ecurie Francorchamps entry of Léon Dernier and Jean Blaton (3757 GT) crossed the line third.

It had been a race in which the leading GTOs had outlasted an array of those ‘experimental prototypes’. In addition to the Project Aston and 330 TRI/LM, there was a 4-litre Berlinetta from Ferrari, a trio of Maserati’s fearsome Tipo 151 coupés, and Count Volpi showed up with his Ferrari 250 GT ‘Breadvan’ – a car born out of his frustration with Enzo, and a whole story in its own right.

GTO debut at Sebring that same year, and a second place

Revs Institute

In July, Carlo Maria Abate took Volpi’s GTO (3445 GT) to victory in the Trophées d’Auvergne at Charade, leaving the little Lotus 23 of Alan Rees to trail home in second, and GTOs then dominated the following month’s Tourist Trophy at Goodwood. Innes Ireland took pole position in 3505 GT, but come the race he was soon overtaken by John Surtees in 3647 GT. ‘Fearless John’ set a series of lap records as he pulled away from the other GTOs, and looked set to add a four-wheeled TT win to his earlier two-wheeled success until Jim Clark lost control of his Aston Martin DB4 GT Zagato while being lapped and took them both out of the race.

A grateful Ireland swept past to take victory, and Bob Grossman maintained the GTO’s perfect record by finishing second overall at Bridgehampton’s Double 400. The championship then came to a close at the Paris 1000Kms in which GTOs occupied four of the top six positions. Leading them all were Pedro and Ricardo Rodríguez in the NART-entered 3987 GT, a poignant result given that Ricardo died a couple of weeks later during practice for the Mexican Grand Prix.

Ferrari’s clean sweep en route to the title was impressive, but the GTO really showed its versatility away from the glare of the world championship. In the UK, Graham Hill did his best to keep on terms in the John Coombs Jaguar E-type, but the likes of Mike Parkes, John Surtees and Innes Ireland were all GTO-mounted and Parkes, in particular, ran riot.

On paper, some of these British events might seem low-key. Twenty-five laps around Mallory Park is a long way – both literally and figuratively – from the Targa Florio, but Parkes, Surtees and Hill were all at the Leicestershire circuit on June 11. And for the feature Formula 1 race that day, the front row comprised Surtees, Jack Brabham, Clark and Hill.

FIA official Filippo Theodoli has the best seat in the house at Le Mans 1962 on the NART’s GTO

Revs Institute

On the home front, privateers Edoardo Lualdi Gabardi and Ferdinando Pagliarini often went head-to-head in Italian hillclimbing. Lualdi Gabardi – who ran a successful textiles business and was a loyal customer of Ferrari – acquired 3413 GT and won first time out at the Coppa Città di Asiago. This was a different discipline to British hillclimbing, on a more epic scale – highlighted by the fact that the Mosson-Treschè Conca course covered nine miles and climbed 802 metres (2650 feet).

Lualdi Gabardi would claim nine class victories during the course of that year and win his class in the Italian GT Championship, but the GTO’s maiden season was not entirely flawless. The Tour de France – still a non-championship event in 1962 – had become a Ferrari stronghold, its gruelling schedule showcasing the all-round abilities of the 250 GT Berlinetta, variants of which had won every year since 1956. Thanks to an unfortunate sequence of events involving a moment’s inattention, a milk lorry and a missing bonnet, it would not be a GTO that continued that run. Lucien Bianchi and Claude Dubois had a comfortable lead aboard 3527 GT as the field made its way from Spa-Francorchamps to Reims for the final race of that year’s Tour, but as they came through the village of Remouchamps, Bianchi went straight through a junction and hit a milk lorry. The damage was extensive, but Ferrari’s Assistenza Tecnica crew worked miracles to get the GTO to Reims.

Sadly, it was for nothing – officials refused to let the car race without its bonnet, which had been left in Remouchamps. The Belgians were classified seventh and victory went to the Short Wheelbase of André Simon and Maurice Dupeyron. Decades later, Dubois remembered that while driving the GTO on a pre-event recce, Bianchi had warned him to slow down because it was a time of day at which the milk lorries would be on the road…

Later in 1962, the GTO chalked up yet more victories, from the Rand 9 Hours at Kyalami to the Nassau Tourist Trophy. In America, however, there was trouble brewing. Carroll Shelby’s Cobra had been homologated on August 6, and the Texan set his sights on taking down Ferrari. He managed it, too, but not until 1965 – by which point the GTO had chalked up three world championships and Enzo, as always, had long since moved on.

Thumbs up at the 1962 Targa Florio for the 250 GTO of Giorgio Scarlatti and Pietro Ferraro

Getty Images