Ford v Ferrari: Stunt Driving and Filming Locations Revealed

The storyline of Ford v Ferrari – the 20th Century Fox film about Carroll Shelby leading the Ford factory team to a podium-packing victory in the 1966 Le Mans 24…

Getty Images

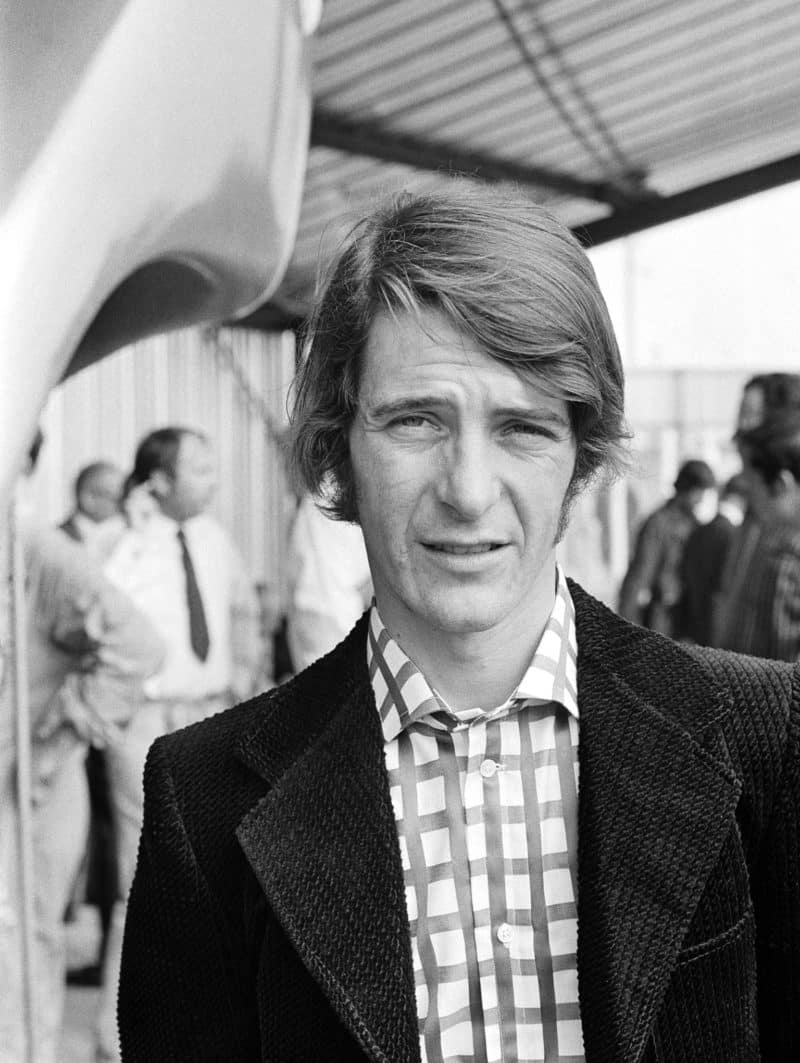

He won the Targa Florio twice, raced for Scuderia Ferrari, had his own grand prix team, created a car that bore his name and saved Niki Lauda’s life among many other highs and lows. He doesn’t do email, speaks very little English and likes to keep a low profile at his home in Milan.

But with the aid of an interpreter, Arturo Francesco Merzario bravely agrees to ‘meet’ over Skype from restaurant Osteria 1927 Enoteca, just a few yards from the Porta Vedano at Autodromo di Monza, the best place for lunch if you’re heading for the Italian Grand Prix. Monza and Merzario, a full-on, passionate, all-Italian affair. What follows is much gesticulation, intense interruptions, laughter and a few unprintable anecdotes.

We start with sports cars and the many victories for which he will be best remembered. And where better to begin than at Spa-Francorchamps – the old circuit, of course – where Arturo excelled for Ferrari, winning the 1000Kms with Brian Redman in 1972. “Fantastic circuit in those days, very dangerous and very fast. The Ferrari 512S was a nice car, great engine, but far too heavy, so physical to drive, five laps and you were already tired. I had driven a Porsche 917 at Imola in 1971 and it was so much easier to handle. The 312 PB was better, lighter, not so demanding on your body.”

Merzario in his prime, complete with cowboy hat

Getty Images

‘Little Art’ always was, and still is, a wiry little guy, fingertips as opposed to biceps. “Remember, nothing was power-assisted, so steering and braking took it out of you, and it was so important to be precise in those long, fast corners. One mistake and you would be in the trees… or a house. The track was not so wide then, and I tell you, it was fast, sometimes scary, no way two abreast at Raidillon. You don’t make a mistake there or you are going to crash. On the big straight after Eau Rouge and Raidillon it was easy 300kph [186mph], no chicane like now at Les Combes, the trees were so close, the car would jump in the air at the top. On the way down to Stavelot there were houses; you had to be so precise, millimetre-perfect. If you hit the house you were not coming back. The most dangerous place was Blanchimont. I felt like I would s**t myself, you were right on the edge there. This Spa was not like today, not at all.”

Sitting below a poster of the 1955 Mille Miglia, and a bottle of champagne celebrating 70 years of Ferrari, Merzario moves on to the Targa Florio, where he was twice a winner in 1972 and 1975. “You know, my secret for road races was my memory. One lap in practice and I had a film of the circuit in my head. It was the same with the Nordschleife, nobody could believe it. Most important was to know all the places to go fast, the places where I could hurt myself, and where the surface was not so good and what you might hit. That’s the secret.

“The speeds were not so high on the Targa Florio then, a lap was about 33 minutes, and when Helmut Marko was chasing me in ’72 he set the lap record, his average speed only 80mph. The challenge was not just the mountain roads, it was also the spectators. They stood sometimes on the track so you had to know exactly where to place the car – they were not going to move. The roads were not closed for practice so there were sheep, goats, donkeys, scooters, people walking around, and you never knew what might be around the corner. Absolutely not possible to have a race like this today, it would be crazy, far too dangerous now.

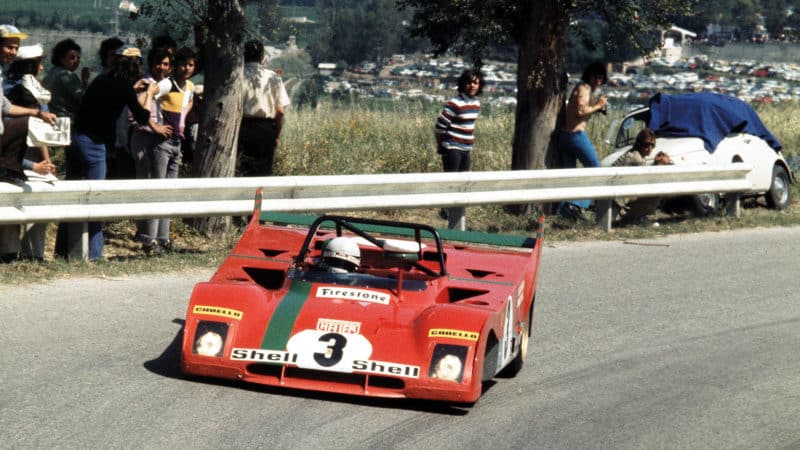

Winning ways at the 1972 Targa Florio in the Ferrari 312 PB, co-driven with fellow Italian Sandro Munari

Getty Images

“Always I was fast on road courses, from the early days with Abarth on mountain climbs, and I won the Sardinia Rally back in 1963 with an Alfa Giulietta, so for me the Targa was a joy, in the Ferrari 312PB in ’72 and in the Alfa Romeo T33 in ’75. You had to pace yourself, this was important, because the race is long and you need to conserve your energy. Porsche would practice for a month, studying every detail, but with Ferrari we went only for a week before the race itself. In ’72, I was with Sandro Munari, a good co-pilot and a rally driver, and we beat the Alfa Romeos, which was nice for Ferrari. Also, you know, it was a very big year for me, starting with Ferrari in Formula 1 at the British Grand Prix, and winning the European 2-litre Sports Car Championship with Abarth.

“I was working in the Abarth factory when Ferrari called. There was a summons over the Tannoy on the shop floor… ‘Merzario, telefono!’ So I took it and a man said, ‘Ferrari at Maranello, I want you to come and see us.’ It was Enzo… but I thought someone was pulling my leg, so I said, ‘Sorry, I am really busy at Abarth and I have a race at Imola coming up.’ The line went dead and I went back to work, wondering who was the prankster. After the race at Imola a man I’d never seen before approached me and said, ‘You must be at Maranello on Monday,’ at which point a journalist appeared and said, ‘I hear you are going to Ferrari.’

“So I went. When I arrived I was shown into a waiting room, sat there for nearly two hours. Then they called me in, Enzo at his desk, an accountant and a lawyer. The Old Man said, ‘I want you to race for us,’ and I explained I had a contract with Abarth. ‘Not your problem,’ he said, and offered me a huge amount of lire – too much, and I told him it was a crazy figure, I was only 24-years old. He looked at his accountant and said, ‘Merzario says it’s not enough,’ – which was typical Enzo. Anyway, I signed and had two years with the team.”

Merzario at a private Ferrari test at Fiorano in 1972

GP Library

In 1972, the Ferrari B2 was a good car and, given only two starts at Brands Hatch and the Nürburgring, he impressed. He took sixth at the British Grand Prix and his first championship point, despite a long stop with a puncture, and placed 12th at the ’Ring. He was in illustrious company, the Scuderia having Jacky Ickx, Clay Regazzoni and Mario Andretti on its books at the time. The 1973 season, alongside Ickx, was a different story. The B3 was a dog and poor results triggered a political storm at Maranello.

“We used the B2 for the first five races and I was fourth in Brazil, fourth in South Africa,” he says. But it was downhill from there, the B3 outclassed by the Tyrrell, the Lotus 72 and pretty much everyone else. “Fiat brought in Sandro Colombo who ordered a monocoque from John Thompson in England, but only one arrived, for Ickx, at the start of the European season. It was a mess, and in the summer Mauro Forghieri came back; he’d already designed a B3 with a big, wide nose, which the media called spazzaneve – the snow plough. Maranello was not amused. This car was put aside, but I worked with Forghieri on my car, we improved it, but things were so bad we missed some races, including the Nürburgring. So Ickx left and raced a McLaren in Germany. There was no car for me in Britain, Spain, Belgium, Sweden or Germany, so at Monza I went to see Enzo – we always had a close communication. I told him, ‘No, I cannot work with Colombo and Giacomo Caliri and all their politics, I leave at the end of the year.’

“He was furious. Nobody said ‘no’ to Mr Ferrari. After practice, he said he was taking Lauda and Regazzoni for 1974, so, I said, ‘Okay, if you want me to go to Canada and America for the last two races I will go, otherwise I don’t care what happens.’ He was like Machiavelli, the way he controlled the team, and it was always the cars that took the glory, never the drivers. When Lauda won the championship, he hated how Lauda got all the publicity and not the Ferrari car, you know? Anyway, he said ‘Okay, you’re on your own, I send one car, for you, then you leave.’ I did two laps at Monza that weekend before the suspension broke. At Mosport, I was 15th, five laps behind, Watkins Glen 16th, four laps behind.”

A rare outing without the hat

Getty Images

All in all, 1973 is not a happy memory, and Arturo had fallen out with Ickx in F1. “As a driver, he was one of the greatest, yes, but always so political, wanting everything his own way. It was trouble if he didn’t get it.”

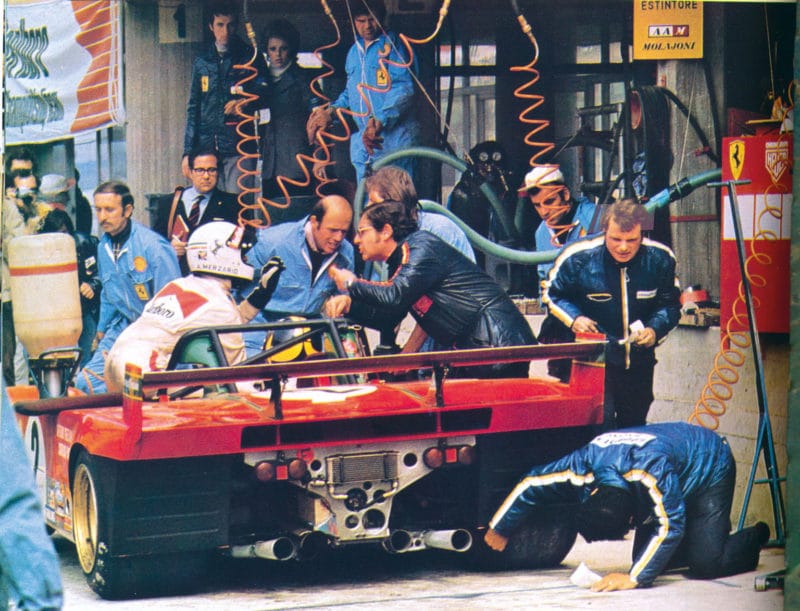

This animosity boiled over at the Nürburgring 1000Kms in May. Running first and second in the 312PBs, Ickx and Merzario were told to hold station at the final pitstops but the Italian had other ideas. He was catching Ickx, came up behind him, ready to take the lead, and tapped the Belgian’s gearbox a couple of times. On the pitwall, all hell broke loose. Forghieri was waving wildly and clutching a hammer, until Merzario had to come in for fuel whereupon he refused to get out of the car to hand over to Carlos Pace.

“I was so angry, I was faster than Ickx, so why should I get out? It was crazy, everyone shouting. I clung to the wheel, but they pulled me out, and I didn’t hang around, went straight to Cologne airport and home. Of course, Pace obeyed the orders, followed Ickx into second place.”

The Ferrari 512S was a tiring car to drive; the Porsche 917 was easier. Merzario takes to the air at the Nürburgring, 1970

Bernard Cahier

The Nordschleife, however, showed him in a very different light at the German Grand Prix in 1976. He was following Niki Lauda when the Austrian crashed heavily at Bergwerk and the car burst into flames. Brett Lunger could not avoid hitting the Ferrari and Guy Edwards stopped nearby. Both jumped out of their cars to help Niki, but it was Merzario who plunged into the fire.

“I just did what I had to do, no time to think,” he says. “I couldn’t release his belts at first, the heat was so intense, the flames were so bad. I made three attempts, and now he was unconscious, so no pressure on the belts, and I dragged him out of the car. I don’t know how I did that. I thought he was dead, he had swallowed his tongue, but in the army I’d learnt how to get it back, and then I did the heart massage, the mouth-to-mouth. We stayed with him, his helmet had been torn off in the crash, he was very badly burned, but when he woke up he asked what his face looked like so I thought he’d make it. “People have many theories why it happened. The track was wet, and from where I was behind him, I think he lost the car on some standing water. Weeks later he gave me his Rolex watch, no ceremony, just handed it to me for saving his life. We were never best friends and I’ve never worn it. But, yes, I still keep it.”

In 1977, ‘Little Art’ took a step too far. He started his own grand prix team, with sponsorship from Philip Morris, with whom he has a lifetime contract and is still on its payroll. For the first year, Team Merzario used a March 761B before building its own cars, struggling for the next two seasons and moving down to F2 before calling it a day.

“You know, by the mid-1970s, F1 was already too technical for me, but all my career I had this great support from Philip Morris, so I could make my own team,” he says. “I loved the driving, was still fast, but we could not compete with the big teams. In ’78, the car was quite good but not reliable. Everyone was doing the wing cars with new aerodynamics, and in ’79 they were copying Chapman’s Lotus. We just did not have the people to build a car like that. It was a mistake, I was too innocent, and at Imola, I went to see Bernie Ecclestone to say it was finished. He was good, he said we could quit without any penalties for not finishing the season.”

What about F1 today? He’s a pundit on the Paddock programme for Italian TV. “It is show business, no? Business with a capital B. It’s so different to my day. I watch Ferrari of course, and Leclerc is a fantastic talent. I just hope he can withstand the pressure. The Italian media is very tough, they talk as if he has won the world championship three times already. Ferrari is still such a political animal, they threaten to leave the sport, but they won’t ever do that. Lewis Hamilton, I think, is a great driver. He races very cleanly, he’s an outstanding talent, and the best in F1 for a long time.”

Finally, some Merzario myths. What about that cowboy hat? It was always a good way of finding Arturo in a crowded paddock but it has nothing to do with the Marlboro cowboy from the ads. “When I first went to America in 1967, the hat was the first thing I bought. I’d always loved cowboys when I was a small boy, and I’ve worn it ever since. I also bought a Colt 45, the real one with the five-bullet chamber, and I still have it at home. Imagine, I came through customs with that gun, but nobody seemed to mind.”

Fury in the Ferrari pitlane at the Nürburgring 1000Kms in 1973, with Arturo stating his case, left, and refusing to let go of the wheel

Bernard Cahier

Another Merzario myth insists that he kept a pack of cigarettes in the race car.

“Yes, this is true,” he laughs, “I taped them to the side of the cockpit so I could have a smoke if I retired from the race. In the Alfa sports cars I had a little hole; I push the cigarette into a ring and it lit. This was good when we did three-hour stints. I stopped smoking on May 26, 2008 after I had a big argument with my mechanic at Vallelunga and I decided no more smoking. I drove home, a full packet on the seat next to me. I kept looking at it, but that was it. I’ve never touched one since.”

Lunch is over, he’s drunk about half a gallon of Coca-Cola, and the tales keep coming. The career stats, despite all those famous sports car victories, don’t tell the full tale. Arturo Merzario remains one of the sport’s most outstanding characters with a special place in the hearts of Italian fans. Once a Ferrari man, always a Ferrari man.

The Ferrari 312B3 was critically off the pace at the 1973 US GP, seen here missing wings in practice

Bernard Cahier

His Brit rival recalls a tough driver who the fans adored

“We used to ask ‘Who’s driving that Alfa T33?’ and it was Arturo. He sat so low in the car, you could hardly see him. He had a weight advantage, too – I reckon he must have been about 80 pounds lighter than me when we raced against each other in the Abarths and the Alfa Romeos. He’s a terrific character, and a great racer, especially in sports cars.

“We never shared a car, being so different physically, but we had some really good races against each other driving for the same team, some great battles. In 1972, we were team-mates at Scuderia Brescia Corse, racing the Abarth-Osella in the European 2-litre Sports Car Championship. We both won some races; Arturo did more races than me and won the championship while Abarth-Osella took the manufacturers’ title. Then in ’75 we were at Alfa Romeo when it won the World Sports Car Championship with the Tipo 33 that year.

Low driving position in the Alfa Romeo T33 at the Watkins Glen 6Hrs, 1975

Bernard Cahier

“A couple of years ago we both went to Balocco to drive the Alfa for a track test and he was the same as I remembered him: such a big character, still wearing that cowboy hat, still that warm and friendly Arturo, and of course the Italian fans love him. He was a dynamic competitor, good enough for two seasons at Ferrari. I think he’d always wanted to do Formula 1 properly for the Scuderia.

“He could be hard on his car, but Arturo was never dangerous on the track. I don’t think he had that ultimate killer instinct but you had to watch out for him as he was always going to be quick and competitive.”

Merzario, left, receives a medal along with a representative of Guy Edwards, Harald Ertl and Brett Lunger for saving Niki Lauda’s life

Bernard Cahier