For the Minsk starters, the flag dropped at 00:34am on Saturday January 18. Facing them was a nine-hour run (back!) to Warsaw on roads that, while not free of ice, at least had no new snow. That was a big relief because snowploughs in the area were few and far between. The biggest difficulties came at the borders, where even special arrangements for the little convoy could not avoid the inevitable bureaucratic delays. Hopkirk had a very worrying experience when he took a wrong turning and encountered a brace of ‘tea cosies’ waving their guns in his general direction.

By 10pm on Saturday evening they were in Prague —and Sunday breakfast was taken in downtown Frankfurt. The day was spent in a foggy tour of the Low Countries, returning in the early hours of Monday morning through the Ardennes and Luxembourg to arrive at Reims just after 8pm.

Bill Price

BMC Competition Dept co-ordinator

“I had a rather short involvement with the rally. My first task was to go with Den Green and Johnny Lay in a car to Frankfurt to service the cars as they came in from the East. It was about six o’clock in the morning and the chosen place was a frozen car park. The temperature was -10°C. There was no problem with the Minis, but we diagnosed a leaking radiator on the MorI9, brothers’ MGB and phoned home to get a replacement shipped out to meet them at the Oostende control.

“While the rally went off to the Nürburgring, we drove to our next service at Arnhem. We picked up the BBC on the radio and it was saying that two British girls in a a Mini Cooper had been taken to hospital in Maastricht after an accident. We guessed that it must be Pauline Mayman and Val Domleo. We headed towards Maastricht and, by the most amazing luck, a chap pulled up alongside us at a traffic light — he had seen the Monte service plates — and asked if wanted him to show us the hospital. We found the girls, left Pauline in bed and took Val back to the scene of the accident for her to retrieve their kit. We then pressed on to Arnhem, where we were happy that there were still no problems with the other Minis.

“The plan now was for us to drive to Paris, leave our car with the Austin dealer, catch a flight to Nice and integrate with the rally service. Sadly, the airport was completely fogged in and likely to stay that way for some time. I rang Stuart Turner, and he said that it was best for us to go home when it finally cleared — which is what we did.”

Stuart Turner

“My role was largely completed & before the rally started it was my task to work out the service arrangements and make sure that all the kit and spares would be in the right place at the right time, and that the teams of mechanics would find their way to the right spot. I remember my wife Margaret insisting that I clear all the maps and paperwork away from the dining room table as we had guests coming for Boxing Day!

“To me, doing the service plan was the most challenging job in rallying — and I loved it. On the event, I would jump into a car with a driver and go round to see the rally at various points. There were no mobile phones or radio so there was no chance to exercise any tactical control. In any case, the rally went straight from Reims to Monte Carlo so we only saw it a few times. I didn’t even make it to the finish ramp in time to see them arrive.”

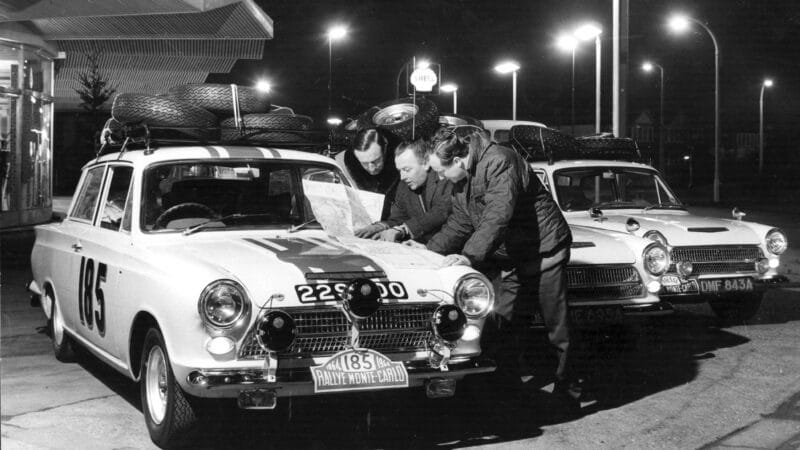

Reims was the central point where all the routes converged, at a large Elf garage on the outskirts of the city. Thirty or so French motorcycle cops were waiting to escort the tired crews to the service park and control in the town centre, in the shadow of the famous cathedral. Their method was to gather a group of three rally cars together, then switch on every available flashing light and siren and head for the centre oblivious of traffic lights, other mad users or the speed limit. For drivers who had already been on the road for 56 hours, this was definitely a wake-up call.

Jose Behra and Pierre Landereau with their German NSU Prinz 4. They’d fail to finish

Associated Press / Alamy Stock Photo

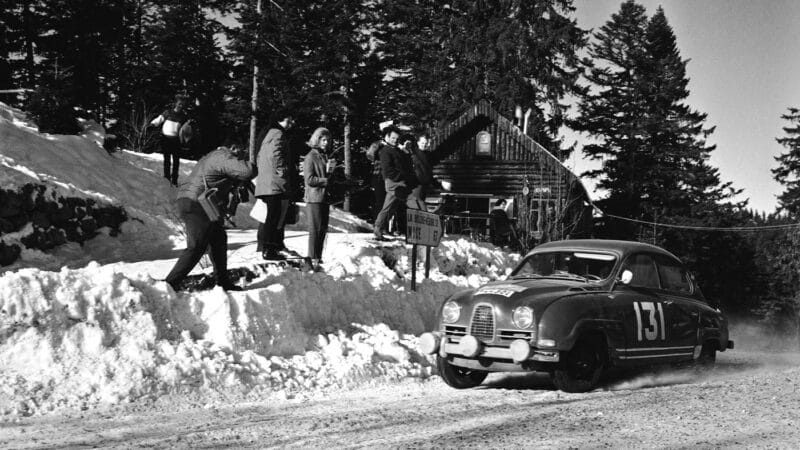

The first cars left Reims at just after 9am. These were the Warsaw starters; the Minsk cars followed them. (If you were an Athens starter, you were not on the road south until 2.30pm.) As Monday night approached, the roads became smaller and more mountainous, while the time controls got closer and closer together. Crews had been arriving with 20 min or more in hand; now they were scrabbling in with just the odd minute to spare.