It’s been not classed as a record because the world championship at that time also included the results from the Indianapolis 500, a totally different category of racing contested by a different bunch of participants. So Ferrari did not win 14 consecutive rounds of the world championship because of that anomaly. But the Indy 500 was not a grand prix so Ferrari does still hold the record for the longest run of consecutive championship status grand prix victories. Red Bull will need to win Spa, Zandvoort and Monza to beat that record.

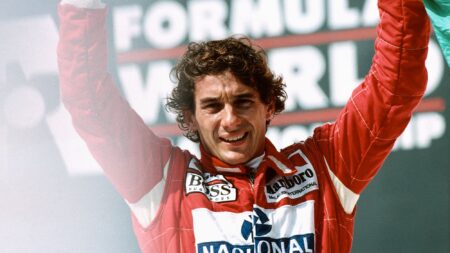

But it’s an interesting exercise to revisit the Hungaroring 35 years ago when McLaren-Honda was in its formidable stride with Ayrton Senna and Alain Prost. Senna won, marking the team’s 10th consecutive victory.

But in a season when the McLarens often qualified 2sec or more ahead of the field (Nelson Piquet had qualified his Lotus third-fastest at Imola with a time 3.35sec slower than Senna’s pole time!), the Hungarian race was much closer than usual. Generally McLaren’s scale of advantage over the 1988 competition was of an entirely different league to Red Bull’s in ’23.

Toto Wolff last weekend commented that Red Bull was like a car from a higher category and the rest of them are racing F2 cars. That’s an exaggeration, of course, but applied to 1988 McLaren it really would not have been. Its qualifying advantage over the second-fastest car (Ferrari) was 1.47% (around 1.3sec), but its race pace advantage was way bigger as the Ferrari could not run the whole distance at full boost on its fuel allocation whereas the McLaren could. Red Bull’s qualifying advantage this year’s second-fastest car (Ferrari again) so far is 0.26% (around 0.2sec) but like the ’88 McLaren its race advantage is bigger.

Just as was the case last year, the ’23 Red Bull RB19’s advantage is borne of the team’s fuller understanding of the nuances of ground effect aerodynamics. A more sophisticated floor design in combination with longer travel, softer suspension with very tight platform control, has delivered a car way more aerodynamically efficient than the others, one in which the downforce is there, low ride height or high, without needing the highest peaks. Just constantly delivered, the aerodynamic equivalent of a low-revving big torque engine rather than a top-end screamer with more ultimate (but less usable) power.

What was the source of the McLaren’s staggering advantage? As always in F1 it was a team effort but the biggest fundamental factor was Honda and how it reacted to the extreme regulation restrictions for turbocharged engines in the final year they would be permitted. At the end of 1985 the FIA had announced a multi-year regulation glide path, with progressively greater restrictions applied to the 1.5-litre turbos year-on-year, the idea being that by the final year of ’88, the naturally-aspirated 3.5-litre with far fewer restrictions would be the obvious choice. Honda thought otherwise and while it worked away on its secret new V10 for 1989, it created a totally new V6 turbo engine specifically around the 1988 regulations, even though it knew it would be obsolete by the end of the season.