“It means you can effectively get the fuel lower in the car, because you can make the bottom of the car sort of square sided, instead of V-shaped, so it drops the centre of gravity of the fuel.

“In that particular case we kind of lucked out a little bit because of the regulations. The reduced size of the engine [Honda being smaller than the TAG-Porsche], the reduced 150L size of the fuel tank that year, the rule which dictated we had to put the driver’s feet behind the axle, it all dictated the layout – it just sort of happened.”

“We had also been able to make some changes on the MP4/3 which also carried over,” points out Nichols. “The MP4/2 had a top radiator outlet, which we changed to the side on the MP4/3 to make it lower and more compact. The rear of the car also maintained the coke bottle shape you can see from above.”

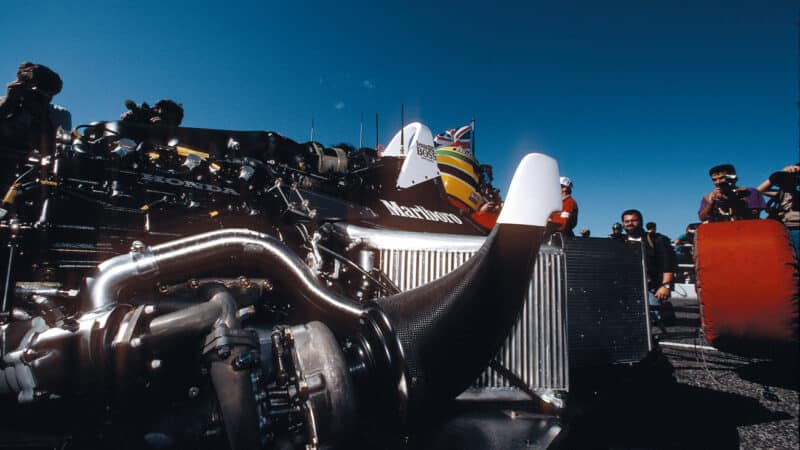

Packaging of the tiny Honda engine was key

Getty Images

Meanwhile Jeffreys, at the suggestion of Dave North, implemented an ingenious idea to solve a front suspension conundrum – once again following the MP4/4’s traits of pragmatism married up with lateral thinking.

“I was the project leader composite/monocoque designer at the time,” he explains. “That was my sort of speciality in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s. I was also put in charge of the front suspension, which we decided would be pull-rod.

“After moving around various options, we came the idea of putting the spring dampers in vertically, behind the driver’s feet.

“It made great packaging sense, kept it low, and there was space to do it – but the problem was this now meant there wasn’t space for a conventional sort of rocker [connecting the strut, as with a standard pull-rod suspension].