When Hollywood Met Le Mans: Steve McQueen's Quest for Racing Realism

Remember the realism of Le Mans? Jonathan Williams does: he was the man hired to drive the camera car, Steve McQueen’s own Porsche 908, in the actual race to get realistic footage. This is his story...

Briton Jonathan Williams and German Herbert Linge shared McQueen’s private Porsche 908/2 during Le Mans in 1970, with the car modified to carry two film cameras

TAKEN FROM MOTOR SPORT, JUNE 1999

Not long ago, I spent a couple of hours sitting at a table in a French hotel, signing my name five hundred times. I was rewarded at the rate of two dollars per scribble, which strikes me as the kind of work I’d like on a regular basis!

The posters to which I added my signature were a limited edition of a fine lithograph commemorating Porsches’ first win at Le Mans in 1970, courtesy of Dickie Attwood and Hans Hermann. All the surviving drivers of Porsche cars in that year’s race had been tracked down by an enterprising American, Michael Keyser, and it was this activity which caused me to think back to that weekend, nearly 30 years ago. In the spring of that year Nello Ugolini, former Ferrari team manager, and at that time working for Scuderia Filipinetti, telephoned me in Rome, where I was living at the time, to ask if I would like to co-drive a Ferrari at Le Mans. I had driven for them at Le Mans in 1968 in their 250 LM, and while that race hadn’t exactly reminded me of Club Med, I accepted the offer at once; it was, after all, the only one I had.

In the perverse way that life functions, the next morning, I found an envelope in my letter box. It was from Andrew Ferguson, an ex-Lotus F1 team manager, and his explanatory letter to the contract it contained outlined a very interesting proposition. Solar Productions, a company set up by actor and racing nut Steve McQueen was planning to make a film based on Le Mans, and unprecedented efforts were to be taken to ensure its authenticity. For a start, all the cars were to be the real thing, no replicas or models, and filming would be at race speed.

For live footage, they planned to enter Steve’s own Porsche 908 in the race, modified to carry two hefty cameras, and they wanted me to drive it, along with German Porsche specialist Herbert Linge. There would be additional camera crews all round the circuit during practice and the race.

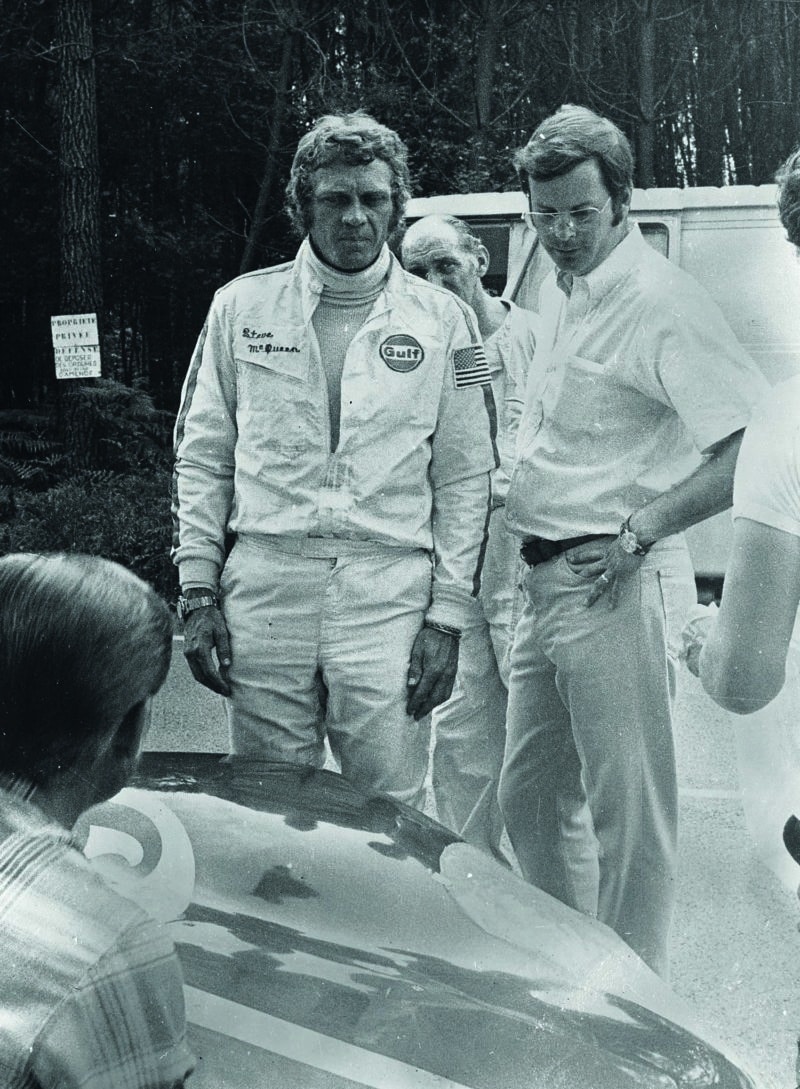

McQueen and director John Sturges. The pair would later fall out

Getty Images

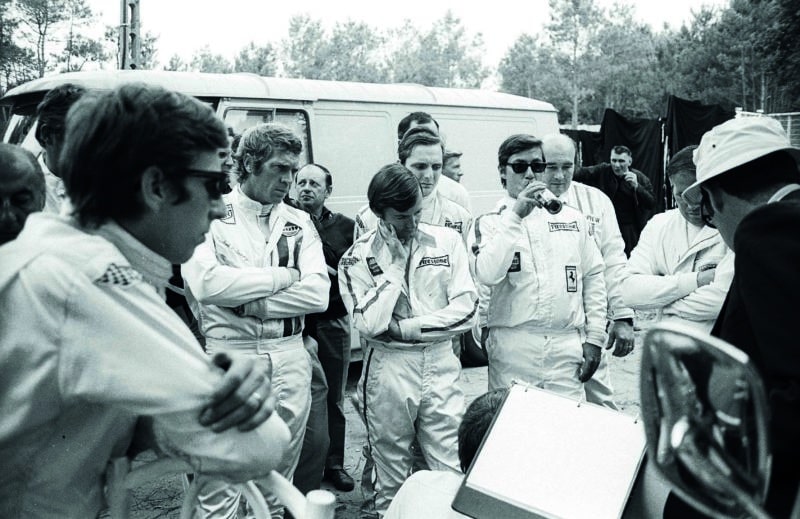

Jonathan Williams front and centre during a meeting with the Le Mans crew

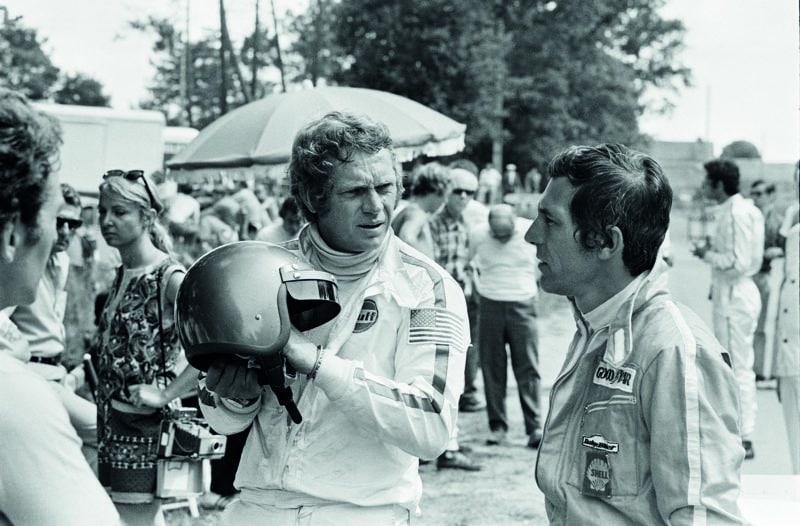

McQueen poses with one of the real Ferrari 512S’s used in the film

After the race was over, they would hire me and other racers to drive cars hired from Ferrari, Porsche, Alfa Romeo and privateers, in the staged sequences needed to fit the film’s story line. When I got to the paragraph in the contract where the terms of payment were spelt out, I couldn’t believe my eyes. Here, for the first, and for that matter, the last time in my short professional career, I was being offered the kind of money that would guarantee some being left over when the work was finished.

Without further ado, I sent a telegram to Andrew, accepting his offer, leaving me with nothing else to do but to make the embarrassing phone call to Ugolini in Modena, informing him of my perfidy. Understandably, he sounded very unamused.

“In the new configuration, the Porsche 908 proved to be very squirrely indeed”

Solar Productions had booked me, along with the other members of the team, into an impressive chateau 20 kilometres from the circuit, which was to be my home for the next two months. Chateau Sagrais was surrounded by a moat, which contained a large population of giant carp, some over a hundred years old, who made a distinctive slurping sound when fed pieces of bread through the dining room window at breakfast time. Inside, there were miles of corridors, leading to countless bedrooms in various towers and turrets, and a kitchen run by a wizard of a chef, whose offerings never ceased to amaze. When, three and a half months later, filming finally ended, I was rather sad to leave.

After checking in, I ran into my great friend from my Ferrari days, Mike Parkes, and he suggested we try a new restaurant in the countryside, about which he had received glowing reports. Inside only one table remained vacant, to which the maitre d’ guided us. Picture, if you will, my horror as we recognised the Filipinetti team seated at the adjacent table, and in the chair closest to me sat Ugolini, the man to whom I had behaved so shamefully! To my relief he simply wagged his finger at me in mock admonition, with a barely disguised twinkle in his eye.

McQueen wanted to race at Le Mans himself as part of the film’s preparation but his insurance company had other ideas

Getty Images

The following morning, I saw the 908 for the first time; it was immaculate, in gleaming dark blue and white livery. I had raced previously in the USA, and knew they took this kind of thing very seriously, more so in fact than most European teams, where even works Ferraris could be fairly described as tatty.

The most obvious change to the car was the bodywork, with the addition of two large glassfibre bumps on the centreline, at the extreme front and rear, whose purpose was to shroud the cameras. These had quick release mounts to enable them, when out of film, to be substituted with recharged cameras, as this had been found to be much faster than replacing the spools. While the aesthetics were rather spoiled by the unavoidable alterations, it was nothing compared to the degradation of the handling of what had hitherto been a very nice car to drive. In the new configuration, the 908 proved to be very squirrely indeed, giving the feeling at all times that one of the rear tyres was going flat.

I can’t say whether this sorry state of affairs was due to the altered aerodynamics, a grey area in those days, or the extra weight of the high-mounted cameras. Today, the whole rig would weigh a few pounds, and use two little lenses the size of a lady’s lipstick. Such is progress.

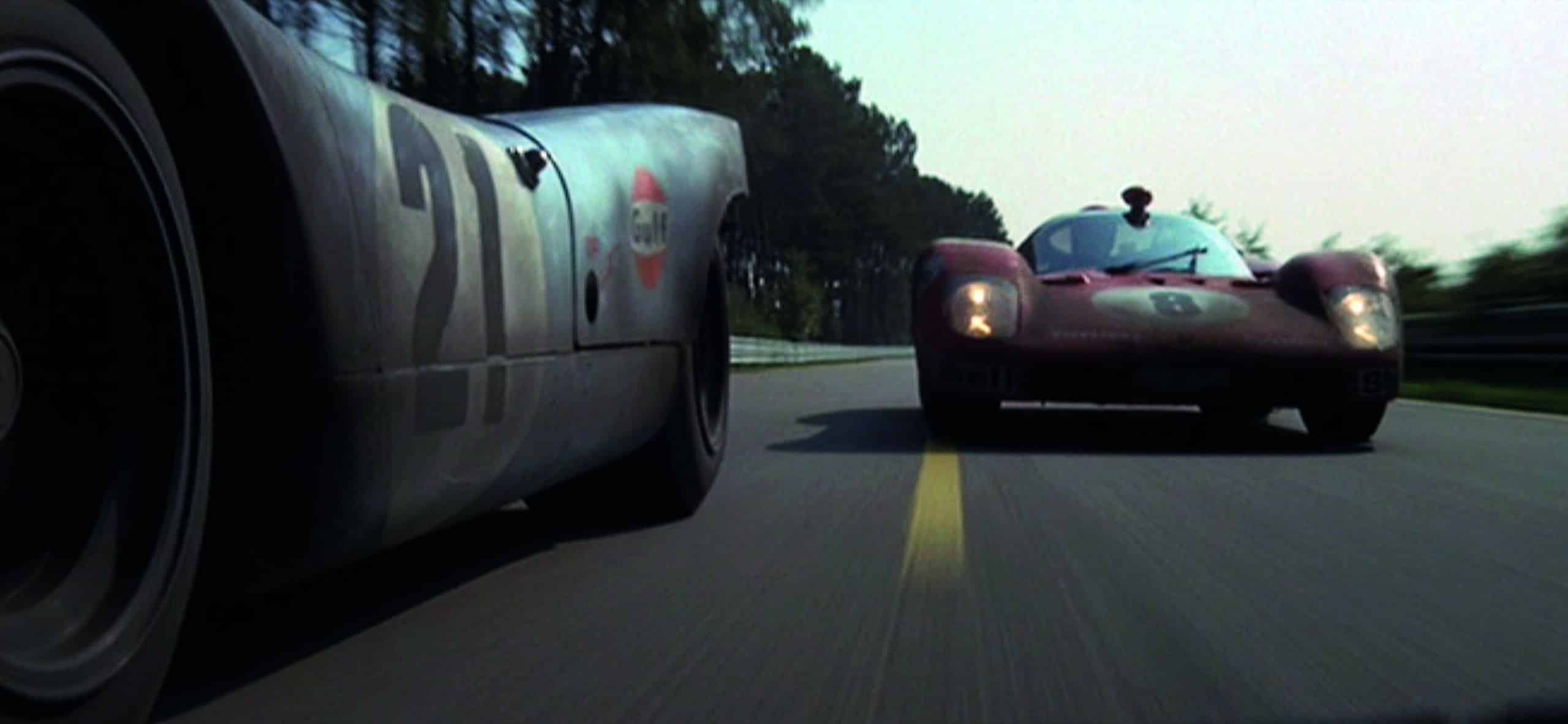

The No29 Porsche 908 with its distinctive bodywork bulges front and rear. Each featured quick-release clips to allow swift access to the cameras hidden beneath

Getty Images

The technicians explained the camera’s control panel, which was situated to the right of the steering wheel. It was simplicity itself, consisting of two on/off switches, mounted in tandem, each with its own red light to indicate that the spool of film on the relevant camera had been exhausted, and a green light to indicate that the camera was running. The film’s director, the legendary John Sturges, explained the kind of shots he hoped to get from us. Of paramount importance, he said, was the start, as this could not be duplicated. He could not emphasise this too strongly. This year was the first time in the history of the race where the drivers did not sprint across the track before scrambling into their cars, firing up, and charging off in a chaotic gaggle. With the new system the drivers were seated in their cars, lined up in front of the pits, in order corresponding to their practice times, waiting for the flag to be dropped whereupon the engines could be started.

Herbert, chosen to start, by virtue of being perceived to have a cooler head than I, was told to activate the front camera about 30 seconds before the drop of the flag, and the rear one just prior to engine start, to record a maximum of mayhem, and to leave them both on throughout the first lap. After that, filming would be selective and at the driver’s discretion. For example when the leading cars, a Ferrari 512S, or one of the Porsche 917s came looming up from behind, they were to be filmed from first sighting in the mirror, and then picked up on the forward camera, pulling away into the distance.

Catching slower cars was to be treated the same way, but in reverse. Filming going through the pit and grandstand area was encouraged, as was recording the same scenes in differing lighting conditions – daylight, dusk, darkness and dawn, plus headlights, tail lights, and grandstands at night. If either of us spotted a car spinning, or passed a stalled car or an accident, the opportunity to film was to be seized, to get a large variety of material with which to weave excitement into the final production. If bad luck dictated we were involved in an accident, I believe they would have liked the cameras to be turning up to the point of impact, but they at least had the good manners not to bring up the subject.

When the flag fell, Herbert got away without mishap, and came in at the end of the second lap as planned, since a film reel lasted around six minutes when running continuously. Driver changes were scheduled for every three hours, to coincide with refuelling. I found this race pretty strange from a driver’s stand point, due to the ultra-frequent pitstops to switch the cameras. Instead of setting out for a normal two- to three-hour stint, assuming all things went well, there was a sort of “see you in a quarter of an hour” feel about each departure from the pits.

These stops were carried out very efficiently and I remember too that McQueen, and members of Solar’s management were usually present, even in the middle of the night. One problem for Herbert and I was that, whereas in normal circumstances you always know where you are in relation to the other cars, here each return to the race found the car at a random place in the order, requiring a high level of vigilance with the mirrors to avoid being run down by a 917 or 512S with impatient men such as Attwood, Jo Siffert or Parkes at the helm.

Naturally, there were times when the film lasted longer, mainly at night; even so I am sure we must hold the record for the number of pitstops made by a car with no mechanical problems as, in typical Porsche fashion, nothing fell off the 908 or broke. It rained through the night, but even though the car was open, very little water entered the cockpit, unlike two years before in the Ferrari 250 LM, when I was soaked and freezing.

Despite completing far more pitstops than others during the race, Williams and Linge stayed well clear of trouble and wound up ninth in the final Le Mans order, but weren’t classified

Getty Images

At around 3am, Solar Productions came very close to getting a lot less footage than they had paid for, when the car aquaplaned coming over the brow after the pits, underneath the Dunlop Bridge. I remember frantically turning the wheel this way and that, while the car floated down the hill towards the Esses, drifting remorselessly over to the left. I remember thinking, “they’re not going to be pleased about this”. In the event, the car caressed the barrier, regained some grip, and, like a well-executed snooker shot, carried on straight as an arrow. Since the car still steered normally, I didn’t come in and pitted on schedule, only for the mechanics to discover a few scratches on the paint work and to wonder what on earth I was wittering on about.

Today, my memory is a little hazy, but I think the rain had stopped by daybreak, and the track began to dry out, as it had the previous time I was there, and for all I know, every year since the race was inaugurated. At the finish, we came home in ninth place, not bad for a car which passed a considerable portion of the race without its wheels going round.

It was the last time I raced at Le Mans which, to be honest, suited me just fine, as, with all due respect to my friend Derek Bell, driving racing cars at simply ridiculous speeds in pouring rain in the middle of the night, was never really my idea of fun.