How Peter Morgan Crafted a Cinematic Ode to 1970s Formula 1

‘It’s entertainment, not a documentary’ has become a mantra for those behind Rush, a film that was born with the help of a Motor Sport correspondent or two…

©Universal Pictures

Motor Sport readers will be the toughest audience to please, given that they are by definition steeped in F1 history. By way of warning, there are scenes that might not ring true. But remember, Rush is emphatically not a documentary.

As it says on the trailers, it’s ‘based on a true story’. Any film has to work as a cinematic experience, and appeal to the world at large – otherwise it would never land the finance to be made. Events have to be condensed, timelines adjusted and some fictional elements added.

What matters is the end result, and Howard and his team have captured the spirit of the era and the key participants’ characters. Most importantly they have created a film that will have broad appeal. It will introduce F1 to folk who have hitherto had no interest, without alienating those who understand it.

Due to commercial constraints, cars were filmed at circuits like Snetterton and then their surroundings reimagined later

©Universal Pictures

At this point I should declare an interest, given that I had an involvement. I first met director Ron Howard and writer Peter Morgan when they attended the 2011 British Grand Prix, and shortly before filming began I was called in to help write some race commentary. Having got my hands on the full script I took the opportunity to go through it and tell them what I thought. It was late in the game, but they listened and some of my unsolicited suggestions did make the screen. I also convinced them that my old pals Simon Taylor and Andrew Marriott would be ideal for the commentary roles. Later, when I was on the set, Ron encouraged me to speak up if I saw anything that caught my attention. To find myself embedded in the production process and see another world from the inside was a fabulous experience.

The man ultimately responsible for Rush’s creation is Morgan. He’s specialised in taking real events and turning them into films, with a CV that includes The Deal, The Queen, Frost/Nixon and The Damned United. His success has given him the rare privilege for a writer of being in a position to create his own projects and see them through to fruition.

Rush began almost by chance after a Hollywood producer asked if Morgan might be interested in writing a 1970s F1 movie.

Brühl’s Lauda sat in a rigged-up tub for a close-up action shot

©Universal Pictures

“My initial instinct was ‘not really’, because I’m not an F1 fan,” Peter says. “But I did a bit of research and I found the Hunt/Lauda story. All I’d heard from my agent was ‘F1 in the 1970s’, so I thought it must be this.

“The elements of the story were very personal to me – because I’m married to an Austrian woman and she knew Niki, because we live in Vienna, and because it was a story about a rivalry between an Austrian and Englishman, it felt very quickly like it was going to the heart of things that were dear to me.

“Then I got the feedback. No, they wanted to do Jackie Stewart. I said, ‘I don’t want to do that, I want to do this’. I’m sure there’s a great film to be made about Jackie, but this had deep tentacles into areas of my own interest.”

With no guarantee that the film would ever get made, Morgan began to put a story together.

“Literally the first step I took was to meet Niki in Ibiza. My wife rang him up. He knew she had married a Hollywood writer, as it were, and he was on holiday and bored, so came over and gave me three hours that afternoon. By the end of those three hours I knew that it was a story that I really wanted to write and, with Niki’s help, I’d be able to do that.”

As many as 35 cameras would be rolling at the same time to capture the action

©Universal Pictures

As many as 35 cameras would be rolling at the same time to capture the action

©Universal Pictures

A pit and paddock complex was built on a runway at Blackbushe Airport. The clever design allowed the building facias to be swapped

©Universal Pictures

A pit and paddock complex was built on a runway at Blackbushe Airport. The clever design allowed the building facias to be swapped

©Universal Pictures

Hunt’s title-winning McLaren M23-8

©Universal Pictures

Understanding what made Hunt tick proved trickier, but he talked to Alexander Hesketh, Bubbles Horsley, Alastair Caldwell and others who knew James well.

As Morgan worked away on a script, British director Paul Greengrass – an action specialist known for two of the Bourne films – became involved in the fledgling project. Meanwhile, over a catch-up breakfast in Los Angeles, Morgan mentioned the story to Howard, with whom he’d worked on Frost/Nixon. Ron liked the concept and wished him luck, adding that if things didn’t work out with Greengrass, he would be interested in taking the reins.

“Literally the first step was to meet Niki Lauda in ibiza” Peter Morgan

“I said if Paul blinks, I’d love to read that script,” says Howard. “It just sounded cool, and I wanted to see the movie. And that’s also a good indication that it’s something I’d enjoy working on.” Sure enough, Greengrass dropped out to do the Tom Hanks movie Captain Phillips, and with fortuitous timing, Howard became available when another project was put on hold.

Filming action shots from Snetterton, which suddenly becomes Fuji in post-production… complete with Norfolk rain and all

©Universal Pictures

Ron had attended the 2008 Monaco Grand Prix with old pal George Lucas, but knew little about F1. Having made Apollo 13, however, and convincingly recreated the world of NASA in 1970, he was the ideal man for the job.

With Howard in and backing secured, a dream team was assembled. Rush features a string of Academy Award winners, including Howard, editor Dan Hanley, composer Hans Zimmer and cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle, who won for Slumdog Millionaire. Just as filming began Mark Coulier – the man responsible for creating Lauda’s burn scars – picked up an Oscar for his role in turning Meryl Streep into Margaret Thatcher in The Iron Lady.

It’s important to note that Rush is not ‘Hollywood goes F1.’ It’s an independent British film, or more accurately an Anglo-German production that just happens to have a hired-in American director. The only people that Howard brought with him from the USA were right-hand man Todd Hallowell, editor Hanley and his assistants.

On one busy day howard had an unprecedented 35 cameras concurrently recording

The rest of the crew were British, apart from a few German technicians, reflecting financial input from that country. Many on the set had grown up in the Hunt era and had pitched for the assignment specifically because of their interest in F1. Howard was able to tap into that passion and knowledge.

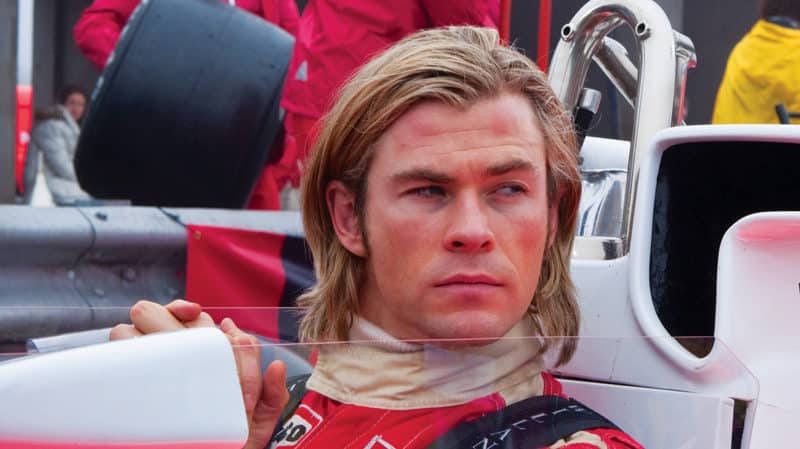

As for the cast, German-Spanish actor Daniel Brühl had the Lauda role from the very early days, and as part of his research attended the 2011 Brazilian Grand Prix with the man he was to play. Finding a Hunt proved trickier, but Aussie Chris Hemsworth – a rising star after his ongoing role as Marvel’s superhero Thor – made a video pitch, convincing Howard and Morgan that he was their man and that he could capture the accent.

Ron Howard with Daniel Brühl on set. Howard reckons he managed to get 80-85% of everything he wanted for the film

©Universal Pictures

After months of research and meticulous planning, the actual shoot took place from February to May 2012 on locations in Britain, Germany and Austria, with the daily schedule planned down to the hour and no safety margin (see right). On one busy day of race action Howard had an unprecedented 35 cameras concurrently recording images, including those placed on cars.

There followed months of post-production, editing, the finalisation of the sound mix (done in Berlin) and the completion of Zimmer’s score. Through the magic of CGI, British visual effects company Double Negative turned Donington Park and Snetterton into Monza and Fuji, created action elements that were otherwise impossible to replicate and ensured a seamless link between the real images captured by Dod Mantle’s cameras.

Howard has now made a series of fact-based movies, and admits that he had sleepless nights when he first ventured away from his roots in fantasy and comedies. It was only after he watched 1950s classic The Bad and the Beautiful – based on life in Hollywood and made by people who knew that world intimately – that he was able to relax, and accept that the hard facts of a story could just be a jumping-off point.

“This film is inspired by facts, but meant to be entertainment” Ron Howard

“I got back to that Shakespearean idea that Peter Morgan hangs his hat on,” he says, “which is understand, adapt and create to offer a greater truth, a human truth, a human observation. That’s what we’re doing with a film like this, which is inspired by facts but meant to be an entertainment.”

Nevertheless, he spared no effort to make the film look and feel right. “It’s important to me to honour the sport and the people who build their lives around it, to try to get it right. That sounds a bit idealistic, but I’d be embarrassed if we didn’t achieve that, more or less. But I also think Rush is very entertaining, and when people hear from others that it’s very authentic, it heightens the experience for them, too. That validation from people who really do know is something that a movie like this really depends upon. To me, that’s really our one advantage over the greats, which were Grand Prix and Le Mans, in that those were fictional. Clearly those are enduring movies, and the best examples. It’s a tricky sport to get right and to capture.”

Brühl spent a lot of time with Lauda to better understand the nuances of his character, and pulled off a terrific performance earning 17 international award nominations for the role

©Universal Pictures

So have Morgan and Howard made the movie they had in their heads when they started out?

“In terms of the story, I think it is,” says Morgan. “But I’m happier with it than I thought I would be in terms of the visuals, and the fact that Ron has succeeded in making great scenes compelling, without being embarrassing. It’s very difficult to make any kind of sports movie in which the actual sporting activity appears even remotely convincing, but I do think they’ve managed to pull that off.

“Because of the way I did this – I just wrote it on my own without taking anyone’s money – then the stakes were quite a lot lower for that reason. If the script had been a disaster, I wouldn’t have let anyone down apart from wasting my own time.”

Howard adds: “You never get 100% of what you dreamed about, I suppose. I haven’t really measured this one yet, but I have to say this is pretty high up there in terms of getting a high percentage of what I was hoping for – maybe 80-85%? It’s gratifying, and it’s nice that we’re getting great feedback.”