Testing and Triumph: The Journey of Aston Martin's Project 212

John Wyer’s final fling with Aston Martin created the beautiful, fast but frail Project cars. Motor Sport recounts a tale of high hopes and dashed chances

In the first week of February 1962, John Wyer called me into his office on the Monday and said, ‘I want to go to Le Mans with a new car.’ You’re joking!’, I said. ‘No, I’m serious. What can you do? And I don’t want just a DB4 tarted up. I want a five-speed box, so use the S532; I want a de Dion axle with outboard brakes and I want it at least three weeks before Le Mans so we can test it.’”

And that is how Aston Martin’s Chief Designer, Ted Cutting, recalled the birth of the Project Cars. This was, in fact, prompted by some of Aston Martin’s dealers, who felt a successful racing programme would help them sell Astons, although demand for the sensational DB4 was already way beyond the company’s capacity.

Owner David Brown was none too keen on the idea but John Wyer, formerly racing Team Manager and now General Manager of Aston Martin Lagonda Ltd, decided to bite the bullet, despite the fact he still had the enormous task of getting the DB4 into proper production. Also, throughout 1961 he had been at loggerheads with Brown, who insisted a DB4-based four-door Lagonda be produced as well. A racing programme was something Wyer could have done without but, having committed Aston to it, he had to see it through. It was from the new Lagonda saloon (designed by Tadek Marek, also responsible for Aston’s new 3.7-litre engine) that Ted Cutting took the de Dion rear axle for his new racer, to be known as Design Project 212. He added both the torsion bars and the trailing links from the DBR2 and put them together on a shortened DB4 GT chassis powered by a 3996cc wet-sump version of the 3.7-litre engine. The 212 was not ready for the 1962 Le Mans Test Weekend, but an undeveloped version of the engine was fitted to an ex-John Ogier lightweight Zagato.

On the test bed this unit produced 278bhp at 5000rpm with megaphone exhausts, 25bhp up on the standard system. This increase was reflected in lap times at Le Mans, for Jacques Dewez recorded 4min 12.8sec; in the 1961 race, the same Zagato’s best time had been 4min20sec, with a 3.7-litre unit. Ted Cutting had been responsible for virtually the whole design of the glorious DBR1 sports-racer, including the elegant bodywork. He now made some sketches for 212 which he took to Newport Pagnell, where sheet-metal worker Bert Brooks and draughtsman Steve Stephens turned his ideas into metal. Two weeks before the race, the 212 was tested at MIRA with no problems. These arose in practice, when drivers Graham Hill and Richie Ginther complained of excessive oversteer and roll, a general lack of adhesion and instability at speed on the straight. Changes were made to the front springs and front and rear shock absorbers, and the next day Hill recorded the fourth-fastest practice time with 3min 59.8secs. The 212’s 4-litre engine was now producing 330bhp at 6000rpm, enough to propel the Aston to 175mph on Mulsanne.

Hill and Bianchi’s DP215 stops during 1963 Le Mans race. Though Hill put up an amazing practice time the gearbox failed, putting them out

Graham made a superb start and led the first lap, but he and Ginther retired on lap 79 with a holed piston. Despite this failure, John Wyer was sufficiently impressed with the 212’s potential to plan two new cars for 1963, DPs 214 and 215.

With these in mind, 212 was tested in MIRA’s wind tunnel in September and it was discovered that the difference between a full and empty fuel tank was a 270lb decrease in load on the rear wheels and a 60lb increase on the front. More worrying was the aerodynamic lift, at 170mph, of 548lb. In light of these tests the 212 was reshaped, with a longer, lower nose and a Kamm-type tail with a spoiler.

Over the winter Aston Martin built two 214s and a 215, but they were playing games with the regulations, as John Wyer recalled in Racing With The David Brown Aston Martins.

“Project 212 had been based upon a cut-and-shut DB4 platform chassis which was too heavy… Both Project 214 and 215 had extremely light box-section girder frames. Because the Project 214 cars were to run in the production class, the new chassis was strictly illegal, but we did not think anyone would look too hard, and so it proved. For the same reason these cars were fitted with 3.7-litre engines, although a loophole in the regulations allowed us to increase the bore from 92mm to 93mm and the capacity from 3650cc to 3750cc.”

Another problem on the 212 was that its weight was too far forward, so on the 214s the engine was moved eight inches back (illegally), giving much better weight distribution.

The 215 was unready for the 1963 Le Mans Test Weekend, so the 214s were accompanied by the modified 212. The fastest 214 time was set by Bruce McLaren in 3min 58.7sec, and Jo Schlesser did an impressive 3min 56.2sec with the 212. The 214s, fitted with combined water and oil coolers from the DBR1, suffered high engine temperatures; the 212 had no such problems as it used the radiator from (whisper it!) a Jaguar E-type and a separate alloy oil cooler. Another problem was with the Salisbury 7HA lightweight rear axle, which failed on one of the 214s, so the DB4-based 4HA was used instead.

Le Mans 1963: Innes Ireland/Bruce McLaren DP214 was leading the GT class until a piston failed.

Shortly after the Test Weekend, John met his great friend and 1959 Le Mans-winner Carroll Shelby in Los Angeles which led to an introduction to Ray Geddes of Ford. Geddes persuaded Wyer to stop off at Dearborn where he talked with Don Frey, Assistant General Manager of Ford. Then, in May, Geddes met with Wyer in England and told him that, as the proposed buy-out of Ferrari had fallen through, Ford had decided to go racing on its own, making it clear that Don Frey wanted John to be involved in the competition programme.

All this time, work had progressed on the 215 which, although virtually identical in looks, was quite different to the 214s, as Ted Cutting explains. “The 215 was conceived as a vehicle on which we could test some ideas which, we hoped, would eventually be found in a V8 production car. We decided upon all-independent suspension. Our idea was to develop from this a suspension for the production V8, with an inboard-mounted spiral-bevel unit developed from the one originally designed for the V12 Lagonda. We decided to use the DBR1 combined gearbox and final drive in the 215 and, instead of coupling it to a 3-litre engine, we went for broke and used a dry-sump 4-litre.” Aston had suffered endless troubles with the transaxle on the 3-litre DBR1, so quite how it could work with an even more powerful engine has never been properly explained. A taste of things to come saw the 215 jump out of gear while testing at MIRA. The revs went sky-high and it bent all the valves… The 1961 World Champion and three-time Le Mans winner Phil Hill joined Aston Martin for the ’63 race, he and Lucien Bianchi being entrusted with the 215. The 214s went to Bruce McLaren/ Innes Ireland and Bill Kimberly/Jo Schlesser. Hill recorded a remarkable 3min 52.0sec, just 1.1sec slower than the pole-sitting Ferrari 330P of Pedro Rodriguez, while Ireland’s 214 lapped in four minutes exactly. Also, Hill and Ireland were credited with the fastest speed of all on the Mulsanne Straight at 300kph/187.5mph, the first time any car had been recorded at 300kph.

“The new chassis was strictly illegal but we did not think anyone would look too hard, And so it proved”

Phil Hill led the cars away from the start, but lay fifth after four laps. On lap 6 he crested the rise after the Dunlop Bridge to find a René Bonnet upside down in the middle of the road. He managed to avoid it, but ran over some debris and so stopped at the pits. Bianchi, who took over at the 26-lap mark, returned immediately to the pits with transmission failure, as several teeth on the input bevel gear had broken. The McLaren/Ireland 214 was leading the GT class, sixth overall, when a piston failed after five hours. The conrod went through the side of the engine, depositing three gallons of oil at the kink on the Straight, causing a four-car crash and, tragically, the death of a driver.

The Kimberly/ Schlesser car was third overall until just after 2am on the Sunday morning, when it retired with another piston failure. It seems that Hepworth and Grandage had designed the pistons as forgings but had made them as castings, due to lack of time. They were simply too light.

“That error cost us the race,” said Ted Cutting. “I really believe those 214s could have finished very well up; they were really excellent cars and two of the best I’ve ever done.” Shortly after the 1963 Le Mans 24 hours, John Wyer told David Brown (but no-one else) that he would be leaving the company in September to join Ford. He had enjoyed a long, successful and very happy association with DB and Aston Martin but was by now disenchanted with both. This was not only due to DB’s insistence on producing the Lagonda, but also to the exasperatingly poor relationship between the company and the unions.

At the end of June, the 215 was entered in a support race for the French Grand Prix at Reims, its specification unchanged from Le Mans. Jo Schlesser’s constant trouble selecting gears resulted in a missed change, which bent two exhaust valves. He still put the car on the front row of the grid, but more missed gearchanges bent the valves again. The 214s were entered for the Tourist Trophy at Goodwood, a happy hunting ground for Aston, so great things were expected of the cars driven by Innes Ireland and Bruce McLaren. Then John Wyer’s chickens came home to roost: the 214s failed scrutineering, not due to the illegal chassis, but because they were on the wrong wheels, as Wyer explains in The Certain Sound.

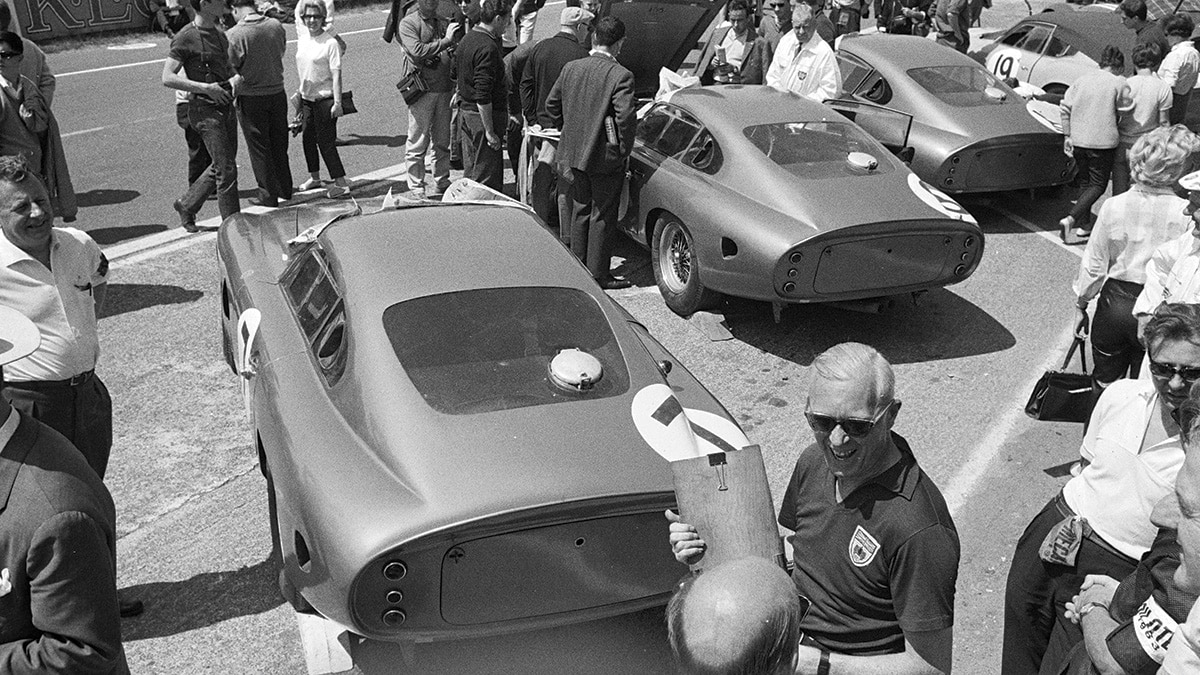

Aston trio at start, with 215 behind the pair of 214s

“We presented the cars [to the scrutineers] on wider rims than those with which the DB4GT had been homologated. We had, in fact, changed the production specification but had omitted to change the homologation sheet. The cars had been accepted in this form at Le Mans, but the RAC Scrutineer, Procter, refused to allow them to run at Goodwood with the wider rims. There were two absurdities about this decision. The first was that, with the only narrow rims that we had available, the rear track was reduced by four inches below the figure shown on the homologation sheet. In neither state, therefore, did the cars conform with the homologation, yet Procter was prepared to ignore the reduction in track, but not the wider rims.

“The second point was more fundamental. The cars had been homologated as variants of the DB4 GT, but the chassis frames bore no resemblance to that car. The engine was also eight inches further back in the chassis. All these changes were sufficiently obvious and if Procter had used them for his ruling instead of relying on a technicality he would have been on firm ground. In the event we ran the cars with the narrow rims, but they were almost undriveable.”

Almost, but not quite. Innes Ireland put up a bravura display in the race, but he could not overcome the Aston’s appalling handling.

“It wasn’t the inch off the rims which killed us,” he said, “it was the 4-inch narrower track, which meant that car just wouldn’t handle. I was absolutely furious. I could have won that race standing on my head…” Innes eventually finished a valiant and angry seventh, but McLaren retired with a bent valve. Happily, the Project Cars’ racing programme ended with a terrific victory at Monza in September. Roy Salvadori rejoined the team he had served so well in the 1950s for the 3-hour Coppa Inter-Europa (which preceded the Italian GP) and had the most tremendous duel with Mike Parkes in a Ferrari GTO. Initially, Parkes led by almost 14 seconds but, by the time the Ferrari refuelled, Roy had whittled this down to 4.3sec and, due to a shorter pit stop, rejoined the race in the lead.

Parkes overtook him, only to be repassed almost at once, and from then on the lead changed continually until Roy won one of the finest races of his career by 100 yards. The 214s had one more race, finishing first and second at Montlhéry against feeble opposition, but John Wyer stunned his team by announcing his departure for Ford and the David Brown racing programme came to an end.

It obviously seemed like a good idea at the time, but Aston Martin’s return to competition was, in reality, doomed to failure. The marque had covered itself in glory in 1959 by beating Ferrari and Porsche to the Sportscar World Championship (winning the Nürburgring 1000 Kms, Le Mans and the Tourist Trophy in the process) with the superb DBR1, only to undo the hard work by persevering with a disastrous grand prix programme in 1960. Apart from the fine win at Monza, the Astons had no success and the programme was undeniably weakened by David Brown’s lack of interest and John Wyer’s preoccupation with other things. In effect, John was Aston Martin racing and, without his whole-hearted commitment, the Project cars had no real chance.