The Mulsanne Straight: Le Mans' greatest blast

The high-speed signature of the world’s greatest race is held in both reverence and fear by those who face it. Now, even cut into three, it still defines Le Mans today. Gary Watkins gets straight to the point

Getty Images

Just over three and a half miles of public road. A flat-out blast lasting not much more than a minute. A place where the fastest cars reached 200mph and beyond. Legends were born here, and brave men died here.

It is, of course, the Mulsanne Straight, a stretch of track that remains at the heart of the mystique of Le Mans 30 years on from its adulteration with a pair of chicanes.

The Ligne droite des Hunaudières as it is correctly known – it’s only called the Mulsanne in the English-speaking world – has been a constant at the Le Mans 24 Hours since the inauguration of the great race in 1923. It might have been cut into three in 1990, but the straight still plays a major part in distinguishing the eight and a half miles of the Circuit de la Sarthe from every other race circuit in the world.

This stretch of road between the cities of Le Mans and Tours – formerly the RN138 but now the D338 after the completion of the nearby A28 motorway – once dominated the thinking of everyone going to the race. “Le Mans meant the long straight in the 1970s,” says former Porsche engineer Norbert Singer, who led the design of a line of Le Mans winners from the 935 to the 911 GT1-98. “When you heard the words ‘Le Mans’ or ‘24 Hours’, you immediately thought ‘Mulsanne’.”

It was no different for the drivers who returned to the French enduro year after year. “If I ever dreamt about Le Mans, it was always the Mulsanne… that bloody straight,” says Derek Bell, who scored all of his five wins at Le Mans before the arrival of the chicanes. “I’d drive through the tunnel under that austere gothic cathedral to go to scrutineering in the city centre and my stomach would tighten. I’d be thinking, s**t, I wonder how fast I’ll be going this year?

“Everyone was pushing to make the cars faster and faster down the Mulsanne. Each time it was a trip into the unknown. You’ve got to remember that from when I first raced at Le Mans in 1970 until well into the 1980s, no one was really using wind tunnels, or at least not sophisticated ones. You had no idea if the thing was going to stay on the road.”

“It was bloody scary, but you’re a racer, so you wouldn’t admit to it”

Andy Wallace, who won on his debut at Le Mans with Jaguar in 1988, remembers being “scared s**tless” when he first encountered the Hunaudières. “It was bloody scary, but you’re a professional racing driver employed to do a job, so you aren’t going to own up to being frightened,” he says. “It probably helped that I was in my 20s and didn’t have a lot of imagination.”

Others had different emotions about the straight. The Mulsanne in all its pre-chicane glory was for sports car legend Henri Pescarolo the beating heart of Le Mans. And the record holder for the most participations in the 24 Hours says that despite sustaining serious injuries in a crash on the Mulsanne during private testing with Matra in 1969.

The run out of Tertre Rouge is crucial for lap time. Even more so back in 1963 when 3.7 miles of uninterrupted straight lay ahead

Getty Images

The four-time winner uses the French phrase ‘scier la branche sur laquelle on est assis’ to describe the introduction of the chicanes, or ‘saw off the branch you are sitting on’. It more or less means the same as ‘to bite the hand that feeds you’.

“The straight was dangerous, but it was our job to race on it,” he says. “The speeds the cars did on the straight was part of the attraction for the public. When the chicanes arrived, we killed the dream.”

Pursuit of speed

Martin Brundle, when asked by this author a few years ago which racing car he would most like to have driven during his career, didn’t say the Lotus 72, the Porsche 917 or the Williams FW14B.

Rather he suggested the winning Jaguar at Le Mans at 1988 “because it was so much bloody faster than our car on the straight”. And when he says “our car” he means the Jaguar XJR-9LM he was driving that year.

The diesel-powered Peugeot 908, and rival Audi R10 and R18, were both geared for torque and as a result were still hugely quick on the Mulsanne. Peugeot’s best was 346kph (215mph) in 2011, the Audi R18’s was 336kph (208mph)

Getty Images

The Jag that went on to win the race with Wallace, Jan Lammers and Johnny Dumfries had a straight-line speed advantage over its sister car amounting to a few miles per hour. That much was evident when Lammers, from sixth on the grid, went screaming past Brundle down the Mulsanne for the first time. The Dutchman would be second by Indianapolis on the opening lap as he exploited his new-found speed on the straights. It mattered not to Brundle that the Lammers car’s increase in top speed had come about by accident. The front ride-height had been raised for the race day warm-up. Lammers insists the change was made in pursuit of more benign handling, engineer Eddie Hinckley that it was actually an error. What’s certain, however, is that it made the car faster on the straight, which is why the crew of the number 2 Jaguar opted to stick with it.

The introduction of two chicanes from 1990 proved divisive among drivers and fans alike, but has ultimately both limited speeds and provided extra challenge

Speed down the Mulsanne was one of the key components to a quick lap at Le Mans and a race-friendly machine that could buzz through the traffic. Ferdinand Piëch, the architect of the Porsche’s 917 as development boss of the company, had an obsession with top speed. It was everything to him. “Piëch had a fixation on straight-line speed,” recalls Brian Redman, who raced for Porsche in 1969-71. “He would never allow his engineers to do anything that would lose the car one kilometre an hour down the Mulsanne.”

This culture remained ingrained in the company psyche at Porsche long after Piëch had departed and a new section of permanent track named in its honour – the Porsche Curves – replaced the public roads through Maison Blanche in 1972. “When we were developing the 956 Group C car for 1982,” says Singer, “the questions from Helmuth Bott [the board member responsible for motor sport] were always about drag and never about downforce. It took Porsche years to understand the need for downforce.”

Death and danger

The Mulsanne was a dangerous place. It claimed the lives of seven drivers, and one more who was killed on the straight as he travelled in his racing car to the pits on the morning of the race.

Jo Gartner was the last fatality on the Mulsanne, in 1986. His Kremer Racing Porsche 962C left the road where the first of the restaurants is located, at a point where he would have been changing from fourth to top gear. The car veered left, became airborne and demolished a section of guardrail. It then struck a telegraph pole and was thrown back across the road.

“When things go wrong on the Mulsanne they go wrong big time”

It has been written that the cause of the crash was gearbox failure, but long-time Kremer team manager Achim Stroth reveals that no explanation was ever determined. “There was a police investigation after the wreck was impounded, but they didn’t find anything that added up to a conclusion,” he says. “There was no verdict.”

What Stroth does know is that just before the car snapped left Gartner hit the brakes hard: there were four tyre marks on the track surface. That appears to rule out speculation about a sudden transmission problem or tyre failure. There was also talk that he was avoiding something or someone on the track. “There were rumours that a marshal was crossing the track,” says Stroth. “Other drivers said that it did happen from time to time.”

Disaster for Mercedes! Mark Webber’s CLR flips during warm-up in 1999. This was the second airborne incident for the Australian. The cars were eventually withdrawn entirely after Peter Dumbreck’s very public acrobatics in the race

Stroth believes that some kind of suspension failure was the more likely cause of the accident. There was no suspicion that driver error was involved.

Win Percy, who walked away from a horrifying accident on the Mulsanne 12 months later, points out that “it was rarely down to the driver when something happened on the straight”. Percy’s accident at the wheel of a Jaguar XJR-8LM in the 12th hour of the 1987 race resulted from tyre failure, something which a new system of infrared tyre pressure sensors on the Jags didn’t pick up because they had become coated in debris. His description of the crash proves that when things go wrong on the Mulsanne, they go wrong big time.

“About 300 metres before the Kink there was a big bang and the car just took off,” he recalls. “There was an explosion and then everything went quiet. I decided it was time to act as though I was in an airplane crash. I took my hands off the wheel and my feet off the pedals, hunched up and waited for the next bang. I was definitely above the line of the trees, floating up in the night sky. Then it came down, bang, and hit the barriers on the left, the right and the left again. After the thing stopped sliding along on its roof, I was more than a couple of hundred metres beyond the Kink.”

Percy stepped out of the car and got a lift back to the pits. He never saw the inside of an ambulance, let alone the circuit medical centre. And when back with his TWR team, he asked if he could go out in one of the other cars!

Driving the Mulsanne

You might think that driving down a straight bit of road would have been easy, save for those niggling doubts in the back of a driver’s mind. It was for the most part: Bell admits that he used to take both hands off the wheel on the Hunaudières.

“I’d hold the wheel with my knees, lift up the visor with one hand and wipe the sweat away with the other,” he recalls. “I could feel the car moving around under me ever so slightly. If a tyre had blown, I’d have been in trouble, but at those speeds I would have been in the s**t anyway.”

But the blast that took the cars through a rightwards curve under acceleration from Tertre Rouge and then into the right-hand Kink two-thirds of the way down the Mulsanne got complicated when it came to passing. “Overtaking wasn’t simple,” reckons Wallace. “The road was cambered up to the centre, whereas the surface of most tracks slopes one way or the other for drainage. Passing someone was a bit of a fiddle at over 200mph. You’d initiate the turn and the camber would push you back down the slope. So you’d put a bit more lock on and have to be careful that you didn’t shoot over the top. You’d be almost on opposite lock as you passed to stop the car going too far.”

The straight had been resurfaced for 1988. Prior to that the problem caused by the domed road surface was exacerbated by the ruts in the road made by the lorries thundering up and down the RN138. “It was like two railway tracks: there were grooves caused by all the heavy trucks,” explains Bell. “You really had to time your move when you were passing someone because you were moving from one set of grooves to the other.”

Then there was the Kink. It was flat-chat, even in the wet, for Bell in a 917 back at the start of the 1970s and Wallace in a XJR-9LM at the end of the 1980s. Just the lightest of steering inputs was required. “I watched my in-car lap in the Porsche 956 from 1983 a while back, and you can’t see my hands turn the wheel through the Kink,” says Bell. “It’s indistinguishable from all those little movements that you were making all the way down the straight.”

Wallace has similar recollections: “It was just a movement of the elbow to go through – you barely moved your hands.”

Drivers took a racing line through the Kink, but overtaking was possible, if not desirable. “The idea was to try to pass before or after the corner, but sometimes you’d gain on someone quicker than you expected,” says Wallace. “I did go through side by side with another car on occasion, but never on purpose.”

Being passed was equally unnerving, says Bell. He remembers Mario Andretti zipping past him – not on the inside, but the outside – in 1988 when they were both part of the Porsche factory squad. “I’d just come out of the pits early in the morning, and I had one of our other cars coming up on me,” he recalls. “It was Mario, who suddenly came around the outside at the Kink. I remember thinking, ‘what the hell?’ because I really had to pinch my line.”

There were challenges, too, for those in the smaller-engined cars that once made up part of the Le Mans field. The fact that they were doing maybe 70mph less than the frontrunners caused its own difficulties.

Legendary Mini racer Alec Poole drove a 1.3-litre Austin-Healey Sprite streamliner at Le Mans in 1968, and he remembers the car being good for no more than 135mph on the Mulsanne. “It was quite unstable at the best of times and when the quick cars flew past it got a bit of wobble on,” he remembers. “You had to be careful that one of the quick cars wasn’t alongside when you changed gear, or you’d probably have flown away into the trees.”

First to 400

The temperatures were going down, so it was time to wind up the boost. Late on Saturday evening in 1988, the little French WM team attempted something that no one had done before, officially at least: break the 400kph barrier, equal to a shade under 250mph, on the Mulsanne Straight.

Roger Dorchy had somewhere in the region of 900bhp behind him and super-slippery bodywork around him as he set out in his WM-Peugeot P88 to raise the record the team had taken the previous year at 381kph. Just before 21:00hrs, its mission was accomplished.

An official speed of 405kph — or 251mph — was declared and shortly afterwards the WM Dorchy shared with Claude Haldi and Jean-Daniel Raulet trailed smokily into the pits. By the small hours of the morning the car was out of the race, its engine rooted by the exertion of his record-breaking run. WM, a regular at Le Mans from 1976, was a happy band of part-timers, mostly engineers from Peugeot. It was led by Gérard Welter and Michel Meunier, the former a stylist with the marque whose credits include the iconic 205 hatch. They did receive support from their employer, but of the technical rather than financial kind.

While the Mulsanne itself has been subject to much change over the years, the run down toward Indianapolis is unaltered since its inception.

As sports car racing became ever more competitive, and expensive, through the Group C era in the 1980s, a team based in Welter’s back garden realised it couldn’t compete with the big boys. That’s where the idea of exceeding the 400kph mark came from.

“We didn’t feel we could compete at the top level anymore,” admits long-time WM technical director Vincent Soulignac, another Peugeot lifer on the squad. “We were a small team and needed a new target. This is why we proposed the idea of ‘Projet Quatracents’ to our sponsors.”

The team set to work producing a car that could be the first to 400 at a time when the record officially stood at 374kph, a mark set by Klaus Ludwig in a Porsche 956 the previous year. The result was the tear-drop P87 that tapered away from bulbous front bodywork into which the wheels were deeply tucked. There were no openings in the body panels save for the nose.

“We had a single mouth at the front for all the air we needed,” explains Soulignac. “From there we separated the air to take it wherever it was required. We were aiming for the best drag coefficient possible.” The P87, he reveals, had little in the way of downforce. The rear wing was present merely to help balance it.

“Dorchy was clocked at 407kph, but a figure of 405 was agreed for Peugeot”

WM actually achieved a speed higher than the official 405kph record, quite possibly much higher. Dorchy was measured at 407kph in ’88, but it was agreed that Welter would declare a figure of 405 in deference to his employer. It was the launch year of the four-door saloon that carried that number.

But Soulingac is pretty sure that Dorchy’s 1988 run wasn’t the fastest ever on the Mulsanne. He reckons that the same driver had gone 10 or so ‘klicks’ quicker the previous year. That’s what the team’s calculations based on gear ratios and engine revs suggested, and the car had already proved capable of such a speed.

The P87 had hit 416kph (258mph) just a few days before Le Mans week, not on a race track but an unopened stretch of autoroute. The run was organised at the behest of French TV channel TF1 on the latest section of the A26 linking Saint Quentin and Laon in Hauts-de-France.

The speed achieved by ex-Formula 1 driver François Migault aboard the P87 was verified by a system that measured the ground speed under the car, as well as the gearing and revs. A third means of measurement in a helicopter carrying TF1’s cameras didn’t work — the aircraft couldn’t keep up with the car!

Come race week, the WM was never clocked at anything close to 400kph. Soulignac subsequently found out that the radar provider, which also supplied the French police force, wasn’t up to the job. This system was still in place for qualifying in 1988 and again failed to register the kind of speeds WM believed it was doing. A new prototype radar trap was subsequently brought in for race day. “For the 416kph run we used commercial fuel because there was no time to arrange race fuel, so we should have been going quicker when we got to Le Mans,” explains Soulignac. “I am convinced that we went faster than 415kph in 1987.”

WM’s official record of 405kph survived through Le Mans 1989 – WM decided not to try to improve on it and Team Sauber Mercedes set a weekend best of 400kph – and so Dorchy’s mark was set in stone when the chicanes went in for 1990.

The adulteration

The Mulsanne in its uninterrupted form – uncorrupted, even – came to an end for the 1990 edition of the 24 Hours. Did the drive for safety play a part in the insertion of two chicanes in its length? It’s difficult to say, but more significantly the straight became a political football in a stand-off between the men in blazers in Le Mans and Paris.

The big race hadn’t always been a fixture on what can generically be called the world sports car championship, as the Automobile Club de l’Ouest (the organiser of the 24 Hours) and FISA (the sporting arm of the FIA at the time) fell in and out of love. But it dropped off the schedule again in 1989 as the result of moves that would have wide-ranging ramifications for sports car racing as a whole.

The WM team and driver Roger Dorchy were the kings of Mulsanne speed, achieving 381kph in 1987 with the P87, then went one better a year later, officially declaring 405kph with this P88, but believe they went quicker

Bernie Ecclestone had been installed as FISA vice-president, promotional affairs in 1987. This gave him control of all FIA-sanctioned series, including what was then known as the World Sport-Prototype Championship. A relaunch of the series with shorter races, Le Mans excepted, and the phased introduction of new rules mandating 3.5-litre engines was announced in December ’88.

Ecclestone made an attempt – half-hearted, say some – to do for sports car racing what he had done for F1 by growing TV revenues. The problem was that Le Mans had its own deals and wasn’t about to hand over its rights. Negotiations that also included the demand for a new pits complex dragged on until May, at which point the Le Mans 24 Hours was struck off the calendar.

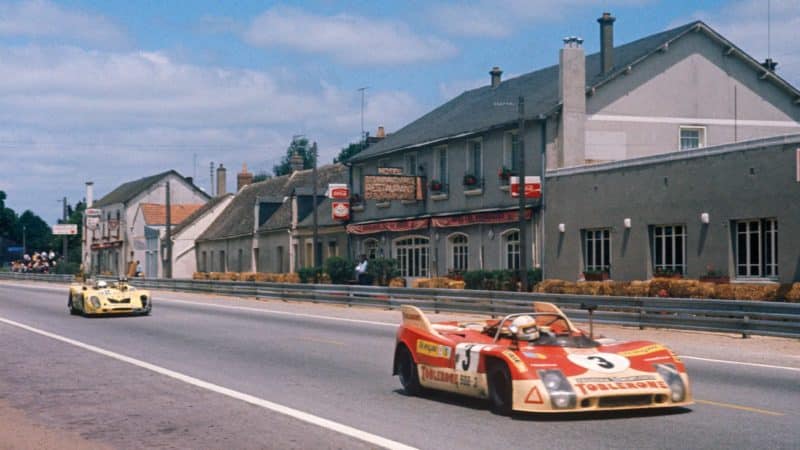

The Juan Fernandez, Bernard Chenevière and Francisco Torredemer Porsche 908 speeds past the Hotel Les Hunaudières in 1973. The restaurant would become world-famous for its post-race celebrations

Getty Images

The Mulsanne was then made a negotiating point in the on-going battle with FISA and its fiery president, Jean-Marie Balestre. With the Circuit de la Sarthe’s track licence up for renewal at the end of 1989, he promised that the straight could remain unadulterated if the ACO acquiesced to FISA’s demands. When an agreement wasn’t forthcoming, Balestre pushed through a new rule that limited the length of any straight to two kilometres (1.2 miles) in the name of safety.

The battle rumbled on into 1990, the ACO trying to involve the French government and FISA publishing a calendar with a 24-hour WSPC round at Spa in early June. Paris eventually prevailed over Le Mans. Two chicanes were built, as were the new pits for 1991, the same year that the race was back on the world championship schedule.

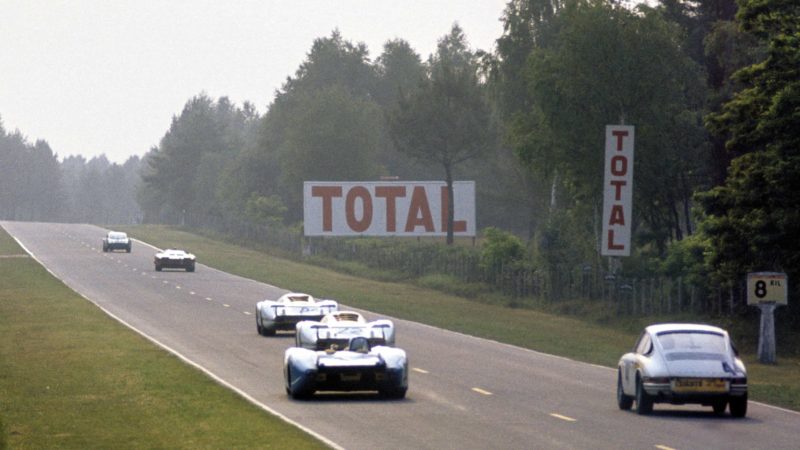

Traffic management has always been one of the biggest challenges of the Mulsanne, with speed differentials of anything up to 70mph between classes

Getty Images

It was a short-lived return for Le Mans, though through no fault of its own. What had become the Sportscar World Championship withered and died in 1992 as manufacturer and privateer interest dwindled in the face of the spiralling costs of the 3.5-litre formula.

The chicanes, of course, remained. The right, left, right shortly after the restaurants is correctly called the Virage de l’Arche, while the left, right, left prior to the Kink is the Ralentisseur or Virage de la Florandiere. They are known to everyone, however, simply as the first and second chicanes.

Best tables in town

The first of the two restaurants located right on the side of the Mulsanne, shortly before the drivers jump on the brakes for the first chicane today, has a special place in the history of Le Mans. It was once a much-used billet for drivers during race week and where the winners riotously celebrated on Sunday night in the 1970s.

The Restaurant des Hunaudières at the Hotel de L’Hippodrome, better known as Génissel’s after its owners, was where Bentley Boy Sammy Davis based himself in the 1920s, while Juan Manuel Fangio and Jean Behra are said to have been regulars when they drove for Gordini in the 1950s. There are even stories of le patron Maurice Génissel kindly – and illegally under race rules – providing petrol to competitors who’d run out of fuel.

But Génissel’s is best remembered for the high jinks on Sunday night at the parties organised by Moët et Chandon. Graham Hill, a well-known party animal, celebrated hard at the restaurant after his 1972 victory aboard a Matra MS670 co-driven by Pescarolo. “There are pictures of us throwing glasses around the restaurant,” recalls the four-time Le Mans winner. “It was a fantastic party.”

Bell remembers going to Génissel’s after the first of his wins at Le Mans in 1975 driving the Cosworth-powered Gulf Mirage GR8. “We definitely partied there after we won with the Gulf,” says Bell of his 1975 victory with Jacky Ickx and the John Wyer-run Gulf Research Racing squad. “You’d quite often end up there anyway, even if you hadn’t won. It could get quite out of hand. One year I remember a girl doing a strip and ending up wearing nothing but a tablecloth.”

The Génissel family, who had taken over the restaurant in 1928, sold out in 1998, and presented the marble sign of their establishment to Ickx. He subsequently donated it to the Le Mans museum in 2006, although it appears that this little bit of sports car racing history has been mislaid in the years since.

A new approach

The addition of the chicanes changed what was required of a racing car competing in the Le Mans 24 Hours as top speeds fell. (The quickest car through the speed trap was a Nissan R90CK at 366kph (227mph) in 1990.) A perfect illustration of this was provided by the fortunes of different teams running the eternal Porsche 962C that year.

The factory-backed Joest Racing team turned up with what has erroneously been dubbed long-tail bodywork, a couple of the privateers with so-called short-tails. The adjectives ‘low’ and ‘high’ would be better words for the respective tail sections because they describe the position of the rear wing in the airflow and thus the downforce they gave.

Despite two chicanes, Toyota’s LMP1 cars are still hitting big speeds on approach to Mulsanne Corner

The works-backed cars struggled with tyre wear, while the independent Brun Motorsport and Tomei-run Alpha teams ended up flying the flag for Porsche.

Tiff Needell, who co-drove the Alpha car that finished third behind the two Silk Cut Jaguars, takes credit for the team’s aerodynamic strategy. It didn’t run a pure sprint-spec tail, rather its own set-up incorporating a shallow rear wing on the high tail. “I’d spotted that the old layout at Fuji was a bit like a one-third scale Le Mans with the two chicanes: it had a long straight and lots of fast corners,” explains Needell, who was racing with Alpha in the Japanese Sports-Prototype Championship that year. “We back-to-backed the two set-ups and did more or less the same lap times, but the car was comfortable with higher downforce.”

Parallel lines

There were various plans for reconfiguring the Circuit de la Sarthe over the years that might have spelt the end of the Mulsanne. One even involved building a permanent section of straight parallel to the public road.

The plan was hatched in the early 1970s in a bid to overcome the disruption resulting from the closure of the main artery between Le Mans and Tours. The Mulsanne wouldn’t have disappeared, just moved one hundred metres or so to one side.

The late Alain Bertaut, a long-time ACO official who also raced at Le Mans on five occasions in 1962-67, remembered that the idea got a long way down the road. “The ACO had bought up 90 or 95 per cent of the land it needed and I’d say that the plan was almost ready when the Oil Crisis happened [in 1973],” he told this writer in 2007. “There was no money and the plans were put in the drawer.”

Never are the speed differentials more apparent than on the Mulsanne. Chevrolet Corvette chases Ferrari 512M out of Tertre Rouge in 1971. Even with the Chevy’s two-litre engine advantage it stood no chance of catching it

Getty Images

A new straight shadowing the original wouldn’t have been the first change to the Mulsanne, as the Circuit de la Sarthe has evolved since its inception in 1920 for that year’s French Grand Prix. The first configuration of the track, measuring 10.73 miles, took the cars deep into Le Mans city before heading south on the RN138 from the Pontlieue hairpin.

This was bypassed by a new section of road, the Rue du Circuit, for 1929 cutting about a third of a mile off the original five-mile length of the Mulsanne. The classic shape of the track at Le Mans we know today was created in 1932 with the creation of a permanent section of track from the pits up to Tertre Rouge.

The corner onto the straight was reprofiled in 1979, and again in 2006. The Mulsanne Corner at its end changed considerably in 1986 as a result of major road works at the junction where the track turned right towards Indianapolis. This created the exciting two-part turn we know today.

The Mulsanne hump on which Mark Webber’s Mercedes-Benz CLR LM-GTP car took off in the race day warm-up in 1999 was reduced in severity ahead of the 24 Hours in 2001.

The bit that’s still old-school

What follows the long straight remains old-school to this day. The run from the tight Mulsanne right-hander to the banked 90-degree left at Indianapolis is unchanged in its line from the day the Circuit de la Sarthe was inaugurated.

Mulsanne Corner to Indianapolis is a 1.3-mile thrash along public road, the D140, that takes the cars over two crests and through a pair of right-hand kinks. It’s flat out all the way until a third jink to the right that’s generally, but not correctly, regarded as part of Indianapolis: the drivers have to shed some speed through it before getting hard on the brakes for the left.

Until 1929 the circuit ran into Le Mans at the Pontlieu hairpin

It is on this section that Jo Bonnier died at the wheel of his self-entered Lola-Cosworth T280 in 1972 when he was launched into the trees after contact with a Ferrari GTB4. It was made famous by the TV pictures of Peter Dumbreck’s Mercedes CLR somersaulting in the air in what was the third aerial incident to befall the German manufacturer that weekend in 1999.

The speeds through this section in these post-chicane days are not dissimilar from those attained on the Mulsanne. Kamui Kobayashi achieved a peak of 331.4kph (205.9mph) before getting off the power into Indianapolis on his pole lap for Toyota at Le Mans in 2019. That’s less than three klicks down on his top speed before the first chicane on the long straight and quicker than his peak on the second and third legs of the Mulsanne.

The curves in the road make this section more challenging than the Mulsanne of today. Former Peugeot and Toyota LMP1 driver Anthony Davidson remembers finding it “pretty daunting” on his first outing at the Circuit de la Sarthe in a Prodrive-run Ferrari 550 Maranello GTS class car back in 2003.

A view of the second chicane. Their addition makes the lap more physical for drivers

The challenge for the drivers of prototype machinery today is overtaking GTE cars through the kinks. “You have to hope that they’ve seen you, and up until a few years ago you were in big trouble if they hadn’t,” Davidson says. “The kerbs have been modified and there’s a bit of asphalt so you can you can run off the circuit if someone hasn’t seen you.”

The challenge today

The big numbers attained on the straight might have disappeared with the chicanes, but their addition has made for a more challenging race track.

“The old straight wasn’t particularly difficult and it wasn’t very physical,” admits Wallace, who made all but two of his 21 Le Mans participations after the chicanes went in. “Now, with two more big braking events, it’s much more demanding on the driver. The level of difficulty and skill required went up with the chicanes. You’ve got to pick your braking points, which isn’t easy in the night. And two extra corners where you are coming down from such big speeds means there’s a lot more scope for racing incidents.”

“You have to choose when to pass… your heart is in your mouth”

For Davidson, now racing in the LMP2 ranks, overtaking on the straights remains the biggest challenge. “The only difficulty you have on the straight is when you catch two GTE cars battling with each other,” he says. “You have to choose where you are going to overtake: that’s when you have your heart in your mouth. You might come up to a couple of GTEs with a P2 overtaking on one side, so you spot a space in the middle and go for it. It can be savage.”

Life still isn’t easy on the Mulsanne when it rains. Seeing where you’re going can be a real problem, says Davidson. “Aquaplaning at high speed is tough, but it’s manageable,” he explains. “It’s the lack of visibility that’s the biggest problem because of the speed differentials between the different classes in the race. The spray is horrendous, to be honest.”

The reason for that is relatively simple. Sustained high-speed running means more water is displaced.

The Mulsanne Straight, or the Hunaudières, is still a quick section – or three sections – of track. It’s an attention-grabber, reckons Davidson. “There aren’t too many places where I’ve been quicker in a racing car, if any,” he says. “You have to give Le Mans that little bit of extra respect and you are conscious of the dangers on the straights.”

But for the drivers today it’s no longer just “that bloody straight”.

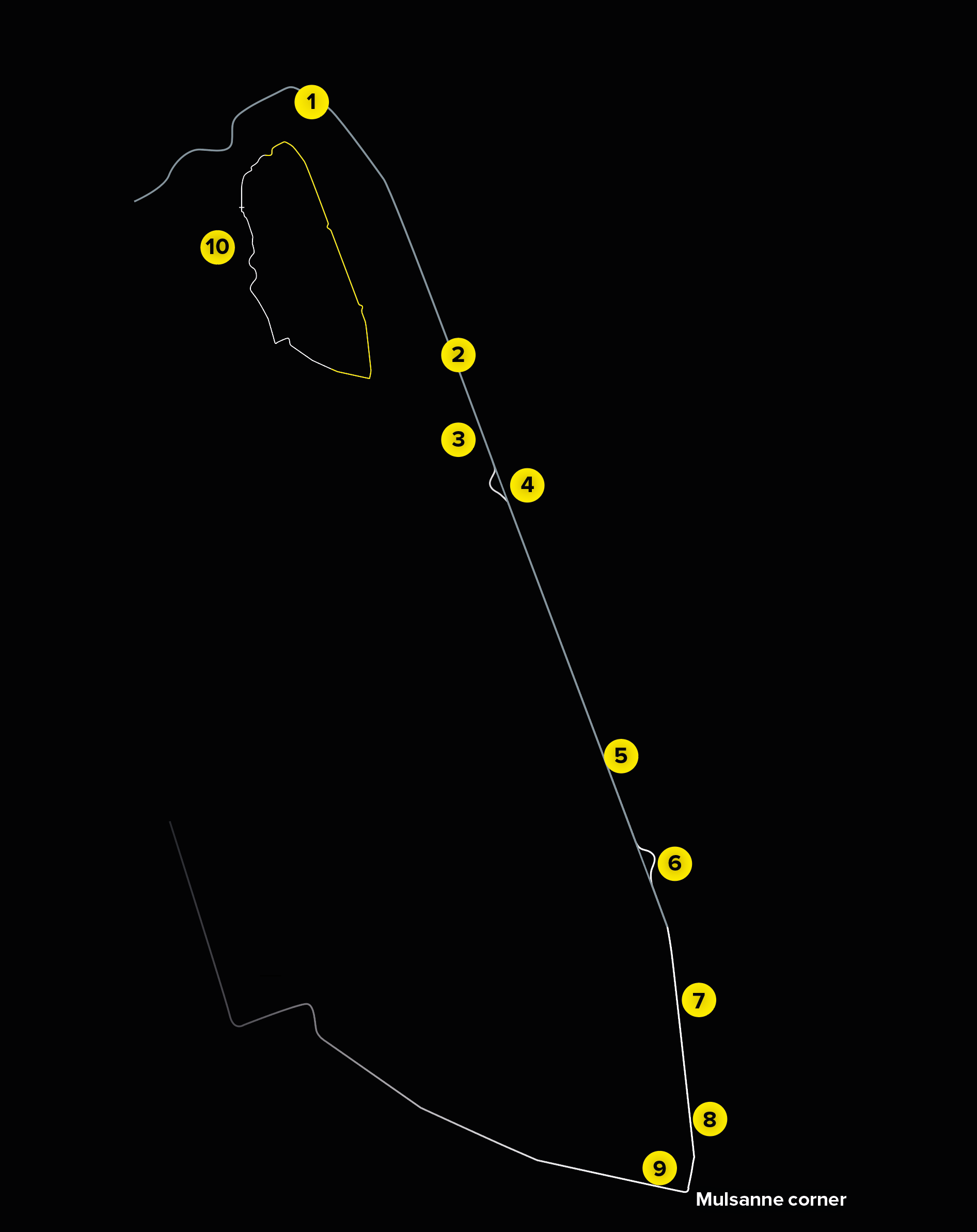

Ligne Droite des Hunaudières

With or without the extreme- speed-limiting chicanes, the Mulsanne Straight has characterised the Le Mans 24 Hours since its first event back in 1923, adding a truly unique challenge to the world’s biggest motor race.

1. Tertre Rouge corner: The fast right-hander marks the end of the permanent circuit, where it joined the RN138

2. As the cars approach their top speeds, the curvature caused by the camber of the road becomes a challenge

3. Hunaudières café and Chinese restaurant

4. First chicane added for 1990 cut the first section of the straight down to 1.2 miles

5. Drivers of the classic Mulsanne would be preparing to take the Kink ahead, hopefully without overtaking

6. Second chicane brings another big stop, opening the door for overtaking and racing incidents

7. The unbroken speed record of 405kph (252mph) was set by Roger Dorchy in the 1988 WM-Peugeot P88

8. The speed record post-chicanes is held by Mark Blundell in a turbocharged Nissan R90C. He hit 366kph (226.9mph) with the dangerously over-boosting engine during qualifying in 1990

9. Major road works have since changed how Mulsanne corner is taken, now making it a double right

10. Track length: 13.6km Lap record: 3:14:791 (2017)

Taken from Motor Sport October 2020