Lunch with... Henri Pescarolo

Perhaps the most famous name in the history of the Le Mans 24 Hours, and certainly its most famous local. Pescarolo has been a racer, a winner, a team boss, and a record breaker...

Getty Images

I’m sitting outside a bistro in the warm Paris sunshine, enjoying a pre-lunch aperitif with Henri Pescarolo. Not for nothing is this man known as Monsieur Le Mans. He has competed in the 24 Hours 44 times, 33 as a driver and 11 as an entrant. Behind the wheel, he scored four outright victories. More recently he’s watched his own cars, built and run on a tiny fraction of the big manufacturers’ multi-million budgets, finish on the podium three years running. In France he’s known everywhere as a hero and a patriot. Passers-by in this busy street stop to shake his hand and say, “Bonne chance, Henri, pour les vingt-quatre heures.”

However, his career has encompassed much more than France’s most famous motor race. His endurance racing spanned 30 seasons, but he also started 57 grands prix, was a frontrunner in the great days of F2 with Stewart, Rindt and Courage, and was French F3 champion in only his second full season. His rallying tally includes 14 participations in the Paris-Dakar. He has been a French helicopter champion. And he holds transatlantic and round-the-world flying records in both piston-engined and historic aircraft.

Pescarolo at Montlhéry, where it all began

Getty Images

Yet he’s quiet, undemonstrative, almost shy: as he says, “I build a wall around myself.” Only when you talk about his continuing will to conquer the 24 Hours – about his battles not only with the big teams but also with the race’s organisers, and what he sees as the constantly moving goalposts of their regulations – only then is the true steel of his character revealed.

Henri and his delightful and resourceful wife Madie, who helps him run the Pescarolo Team, both appreciate good food. The atmosphere in Le Comptoir du Relais Saint-Germain is classic Left Bank: unpretentious, cramped and noisy. Its owner, the legendary chef Yves Camdeborde, is an old friend of the Pescarolos, and our meal is overwhelming. The six courses, each small and beautifully presented, comprise haddock mousse with caviar; ravioli stuffed with lobster, in a lobster bisque; a slice of delicate white féra fish from the Swiss lakes, with watercress; black Basques pork, roasted with asparagus; a glorious rural cheese which the waiter assures us is known only as “the cheese with no name”; and, as dessert, a creamy grapefruit crumble. The Côtes du Rhône that Henri selects to accompany this feast seems, to my untutored palate, to enhance all of it.

Getting a pep-talk from Frank Williams in 1971

Getty Images

Henri’s father was an eminent Parisian doctor, and it was assumed that he’d follow the family calling. As a boy he enjoyed driving his father’s Triumph TR3 around the garden when his parents were out, but he had no interest in motor sport. Aircraft were his passion, and he held a pilot’s licence before he was legally old enough to drive a car. But in 1964, when he was a 21-year-old medical student, he heard an item on the radio that changed his life. It was about Operation Jeunesse, a scheme to address the lack of young French talent in motor sport.

Sport Auto editor Jabby Crombac had arranged for 19 car clubs all over France each to be given a Lotus 7, for which they had to find promising drivers. Jabby got Ford France and radio station Europe 1 to foot the bill, and over 10,000 French youngsters applied.

“It sounded like fun, so I put my name in. For the Paris area there were elimination trials at Montlhéry, organised by the local racing school. I had to do some laps in a Triumph TR4, which was like my father’s old TR3, and at once I felt at home. I had never seen a race track before, but my lap times were faster than the instructor’s, so I was selected. Who else can say: the first motor race I ever watched, I watched from the cockpit. And I won it.”

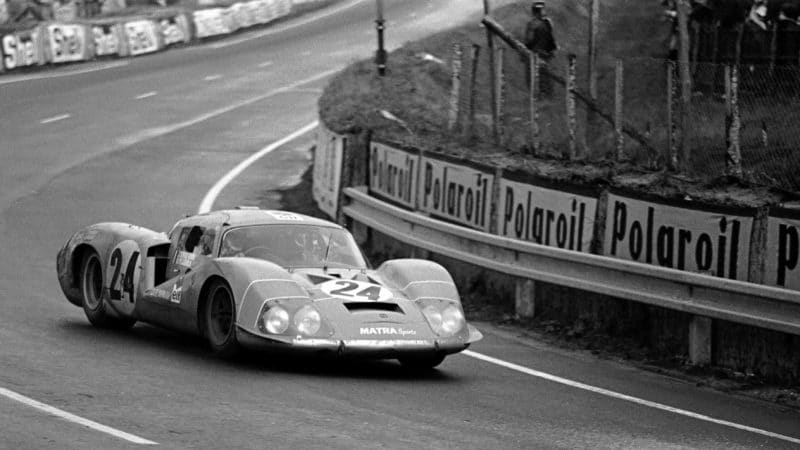

At home at Le Mans in the 1968 Matra with Servoz-Gavin

Getty Images

After more wins, Henri’s father was told he had serious talent and should be helped towards Formula 3. However, Dr Pescarolo showed no inclination to buy him a single-seater and Henri, assuming his racing career was over, prepared to return to his medical studies. But Jean-Luc Lagardère, the mercurial boss of Matra, had noted Henri’s speed in Operation Jeunesse and was eager to sign him. “I was to be the test driver. In fact I cleaned the wheels, swept the workshop floor, went shopping for parts, did everything except drive a racing car.

In the end they let me do a few races, and in 1966 I found myself in the F3 team with Jean-Pierre Beltoise and Johnny Servoz-Gavin. At Pau I had a big crash and I destroyed the car completely. Lagardère said, ‘Next week it’s Montlhéry. If you want to race there, mend the car yourself. Nobody will help you.’ I had to strip it, repair the bent monocoque, build it up again. I worked day and night, didn’t sleep for a week, but I got to Montlhéry. And I won.”

Also in 1966, Henri had his first taste of Le Mans, drafted into the three-car team of M620 Matra-BRM coupés at the last minute when another driver dropped out. “It was my first big race. My co-driver, Jean-Pierre Jaussaud, drove for most of practice. Right at the end of the session, late at night, they told me, ‘OK, get in and qualify.’ I had never driven the car, I didn’t even know where the track went, it was dark and the headlights weren’t very good. At 170mph in the traffic on the Mulsanne, I had the works Ferrari P3s and 7-litre Fords coming past, fighting for pole. I tell you, it is the only time I have ever been frightened in a car. But I qualified, and in the race we did eight hours before the oil pump broke.”

With countryman Jean-Pierre Jaussaud his first Le Mans team-mate

Getty Images

Now Henri set his sights on the French F3 Championship. “But not just the French races: Matra was running at Brands Hatch, Barcelona, Monaco, Zandvoort, against all the European teams.” Henri scored 11 victories – including the prestigious Monaco GP support – and duly won the title. “So for 1968 I was in F2, which in those days included the Formula 1 drivers, so I was racing with my heroes: Jim Clark, Jackie Stewart, Graham Hill.”

Although Beltoise won the 1968 European F2 Championship for non-graded drivers, with Henri as runner-up, an unofficial points tally across all F2 races that season shows Henri second only to F2 king Jochen Rindt. And at Le Mans, the Matra MS630 coupé now had the F1 V12 engine. By 11pm on Saturday Henri and Johnny Servoz-Gavin were lying second overall.

“Then about 02:00hrs it started to rain, rain, rain. Big storms. While Servoz was at the wheel the windscreen wiper broke. He came in, said it was impossible to drive the car with no wiper, and got out. The mechanics tried for a long time to fix it, losing many laps, but the wiper motor was inside the chassis, impossible to reach. I was trying to get some sleep, although I never really sleep at Le Mans. Jean-Luc came into the caravan and said, ‘We are retiring. The motor…’ That was normal: usually when we retired at Le Mans it was the motor. ‘No, no, the wiper motor.’ For me that was stupid, we had fought so hard, and to retire for a wiper, we could not do that. I told Jean-Luc we had to try.

“I got in the car, drove down the pitlane and onto the track, into the darkness, into the rain, and I thought, of course, this is impossible. But then I thought, we have nothing to lose, so if I hurt the car it doesn’t matter. I was catching cars all the time, each time I saw a blur of a red tail-light I had to decide, do I go left of it, do I go right? I knew if I put a wheel on the grass I would be in the trees. Each lap I thought would be the last, and I was completely relaxed in my mind, I was happy. By the time it got light, we were in second place again.”

They were still there when, around noon on Sunday, Mauro Bianchi’s Alpine crashed in flames. From the wreckage strewn across the track Henri picked up a puncture, and the flailing tyre damaged bodywork and electrics. With four hours to go they were out. Henri was learning that Le Mans was a place of both superhuman effort and crushing disappointment.

And also a place with dreadful potential for injury. For Matra, Le Mans was now the major goal, and for 1969 it suspended its F1 programme to concentrate on it. In search of extra straight-line speed aerodynamicist Robert Choulet was hired to develop the MS640, a dramatically shaped coupé with high fins. It wasn’t ready for the Le Mans test in April, but later that month Lagardère persuaded the authorities to close the Mulsanne Straight – the main N138 from Le Mans to Tours – for a few hours. Soon after 9am on a Wednesday Henri inserted himself into the long, low coupé and set off. He was still warming the car up, doing no more than 155mph, when the car became airborne.

“It’s all about the critical point. In a fully laden Boeing 747 you can do 400kph and it will never take off, but then you put on two more degrees of flap and up you go. Everything felt good, but passing the small bump by the Hunaudières restaurant, suddenly it was the critical point and the car came off the ground. There were no guard rails in those days. I went up into the trees, and the car flew for 250 metres.

Henri was laid up in hospital following his horror crash during testing

Getty Images

“As it came down it exploded. I was strapped into the burning wreck, fully conscious. The pain when your body is on fire, I cannot describe it to you. Fire burning my body, my face, my eyes. I couldn’t see, I lost all ability to analyse what was going on, I didn’t know how or where to get out. Trapped in a fire like that, you do not survive more than 20 seconds. I still don’t know how I got out. It was not an official test, so there were no marshals, no ambulance, but a passer-by ran up, pulled off his coat and wrapped it round me to put out the fire that was burning on me.”

“There were no guard rails. I went up into the trees, and the car flew for 250 metres”

With a broken leg and cracked vertebrae as well as severe burns to his face, arms, legs and torso, Henri spent a long time in hospital. “In those days we knew that every weekend we could die in a race. That was accepted, we did not worry about that. We did worry about being in a big crash, then coming back to racing – and not being as fast as before. I lay in hospital thinking, ‘Maybe when I start again I will not be quick any more.’ The crash was on April 16, and on August 1, still feeling my burns, my face still not in good condition, I was at the Nürburgring for the German Grand Prix.”

The F1 field was boosted by a dozen F2 cars, so Henri found himself in a 1600 FVA powered Matra MS7. He not only came home first of the F2s, he achieved a remarkable fifth place overall, unlapped after two hours around the ’Ring. “On that circuit especially, it proved to the team, and to me, that I hadn’t lost my speed. For 1970 Lagardère put me in the F1 team with Beltoise. The V12 Matra wasn’t as strong as the Cosworth cars, but I was third at Monaco. At Spa, in fourth, I ran out of fuel with a lap to go, and I was in the points at Clermont and Hockenheim.”

Third at Monaco for Matra was F1 peak

Motorsport Images

For Le Mans, Matra had discarded the Choulet coupé and reverted to the MS650/660 design of Bernard Boyer. “Bernard’s cars were not the fastest on the straight, but they were quickest around the lap, with a very rigid chassis and the best compromise between speed and handling.” But that year engine failures stopped all three. “We also did the Tour de France, running two Le Mans-spec V12 Matra 650s on the road: great for the public. The journalist Johnny Rives squeezed in with me, but a puncture on the Mont Ventoux hillclimb delayed us. So Beltoise won, with Jean Todt beside him, and Johnny and I were second.”

Things were looking good for 1971: then Lagardère delivered a bombshell. Chris Amon became available, and Pescarolo was abruptly dropped. “Jean-Luc created my career by hiring me in 1965, and he destroyed it by firing me in 1970. My F1 career never recovered from that.

“I managed to get a drive with Frank Williams, who was running a March, and I was in the points at Silverstone and Zeltweg, but the car was not competitive because Frank had no money then. It is the vicious circle of motor racing: if you aren’t in a good car, you don’t get good results, so you don’t get a good car. At the same time, in sports cars I had good cars, and I got good results. So F1 people wrote across my back, ‘sports car driver’.

“But Frank Williams is a fantastic guy, and I enjoyed my two years with him because of his wonderful personality. Even when he had no money, his car was always perfectly turned out. And I drove for Frank in F2 as well, and had two wins. Later I drove for Ron Dennis in his Rondel F2 team, and won a couple of races for him. But Ron’s personality was the opposite of Frank’s. He did not like having a French driver, and I found it difficult to work with him.”

Henri persevered with F1, bringing Motul sponsorship to BRM for 1974. “But it was the end of BRM: no more money, no more development. And in 1976 I drove a Surtees run by BS Fabrications, which was Bob Sparshott, a very good guy, but it was only a private effort.”

Not bad for an ‘old man’. Pescarolo and Hill celebrate Le Mans success in 1972. Here

Getty Images

But in sports cars Henri’s standing continued to soar. After his break with Matra he drove for Alfa Romeo in 1971, his 3-litre T33/3 beating the 5-litre Porsche 917s and Ferraris to win the BOAC 1000 at Brands Hatch with Andrea de Adamich. “I loved driving for Autodelta. Carlo Chiti ran the team, a big man sitting in the heat of the pits wearing his dark grey suit and tie. For him, a racing car was all about its engine; the rest of it didn’t matter. So we had a strong engine, but the rest of the car was not so good. But the drivers were all fine guys, with great spirit: Galli, Stommelen, Hezemans, Merzario.” Chiti didn’t think his engines would last 24 hours and missed Le Mans, so Henri shared a Filipinetti Ferrari 512M with Mike Parkes.

“I said, ‘No way I am driving with that old man!’ I was wrong about Hill”

“Parkesi” crashed it in the night. “Then Crombac said to me, ‘You must go back to Matra, they have a car now that can win Le Mans.’ I said to him, ‘I will never drive for Matra again. Tell Lagardère to f*** off.’ But Jabby kept calling me. In the end I thought, ‘I am being stupid about this. If I have a chance to win Le Mans, I must forget my pride and go back to Matra.’ So in the end I said, ‘OK. Who will be my co-driver?’

“Jabby told me I would be with Graham Hill. ‘No way’, I said. ‘I am not coming back to Matra if you want me to drive with that old man. He has not been to Le Mans for years. In the night when it is raining, and in the morning when there’s fog, he’ll be slow.’

“Jabby said, ‘Henri, think about it. He has been F1 champion, he has won the Indy 500, now he wants to be the first man to win all three with Le Mans. His motivation will be sky high.’ So I signed – and I was quite wrong about Graham. He was fantastic. We worked hard together in practice and, you know, we won the race because in the night and in the rain he was so fast. He really, really wanted to win. At Le Mans your team manager gives you a strategy – a time you must keep to, so you do not go too hard and break the car. But if it is wet, and the conditions are inconsistent, you are released from the strategy, because the team manager cannot tell you what lap time to do. So in the night, in the rain, Graham and I were going flat out, and our team-mates François Cevert and Howden Ganley were too. Then Ganley was hit by a Corvette and needed repairs, and we won by 10 laps: the first French victory at Le Mans for 22 years.”

The start of Le Mans 1974, Henri would rack up his third-straight win

Getty Images

The next season, 1973, was maybe Henri’s best ever. Matra fought a season-long battle with Ferrari for the World Sportscar Championship, and by winning five of the 10 rounds – Le Mans included – Henri and his now regular co-driver Gérard Larrousse clinched the title for Lagardère. “Some drivers in endurance races have to show they are quicker than their co-pilots, they think they are driving against them. Gérard and I didn’t worry about which of us was quicker, or what the journalists or the spectators thought. All we cared about was keeping to the plan, winning the race and the championship for Matra. But that year at Le Mans the Ickx/Redman Ferrari 312P was as quick as us. By then we knew our engine was reliable, so [sporting director] Gérard Ducarouge told us to go flat out, all the time. It was like a 24-hour grand prix. With 90 minutes left we were leading, Ickx was second: and then his engine blew. We won, by six laps from Merzario/Pace’s Ferrari.”

Proof of the pace of sports car racing came in that year’s Spa 1000Kms. “I always loved the very fast circuits, holding the car in a 300kph corner like Burnenville on the old long Spa.” Henri’s best race lap in the MS670, at an average speed of 163mph, still stands as the fastest lap ever of any road circuit, and was 14sec faster than Chris Amon’s F1 lap record. Even around the tortuous Nürburgring, in qualifying for the 1000Kms, the Ferrari and Matra sports cars’ times would have put them mid-grid for the German Grand Prix.

In 1974 Henri made it three Le Mans victories in a row, again with Larrousse, and despite a major gearbox problem. “We had a big lead, but on Sunday morning I stopped on the Mulsanne Straight with no drive. I had to take off the rear bodywork, which normally took two mechanics, and I managed to engage a gear. I got the car back to the pits and the mechanics rebuilt the gearbox in 47 minutes. We still beat the van Lennep/Müller Porsche by six laps.” After that Matra withdrew from racing.

“So for 1975 I went back to Alfa Romeo, and I won at Spa, Zeltweg and Watkins Glen with Derek Bell. Derek is a fantastic driver – I knew him right back to our F3 days – and, like Larrousse, he wasn’t interested in showing how quick he was, he wanted to work together for the win. In 1976 I turned down a drive with Porsche at Le Mans to join a new French team with Jean-Pierre Beltoise, in a car built by Jean Rondeau and backed by the Inaltera wallpaper company. We won the GTP class, and finished eighth. I think maybe Beltoise is one of the best French drivers of all time. He has a weak arm from a motorcycle racing accident, and of course when he raced in F1 there was no power steering, no paddle shift. With two good arms I think he would have been world champion. He had the real killer will to win.

Henri relaxes in the Rondeau pit, 1979

Getty Images

“The next year I did do Le Mans with Porsche, in the 936 with Jacky Ickx, so I knew I had the best car and the best driver. The car was perfect – and then, after only four hours, I was lapping to strategy when the engine broke. Porsche’s team manager Manfred Jankte told the press I had over-revved. I had been keeping exactly to the rev-limit, so that upset me. Back in Stuttgart they found a conrod had snapped due to a manufacturing fault.” The exonerated Pescarolo was invited back by Porsche the following year, again paired with Ickx, but after early problems Jacky was switched to another car and Jochen Mass was put in with Henri. They were lying sixth when Mass crashed on Sunday morning.

Henri spent the next four Le Mans with Jean Rondeau’s team, retiring each time, but had several good runs in other races with Bob Wollek in Kremer- and Loos-run 935 Porsches, winning WSC rounds at Suzuka, Dijon, Misano and Vallelunga. In 1982 the little Rondeau team mounted a serious attack on the WSC. In a straight fight, it scored 62 points to Porsche’s 60, helped by Henri’s outright win with Giorgio Francia at Monza. Then Porsche, having failed to score in its home race at the Nürburgring, realised that a privateer 911 had come second in its class there, and claimed its points. The FIA big-wigs deliberated for a month, and finally – because, Henri reckons, they didn’t want their big championship to be won by a small manufacturer – they allowed Porsche to keep those points and thus the world title.

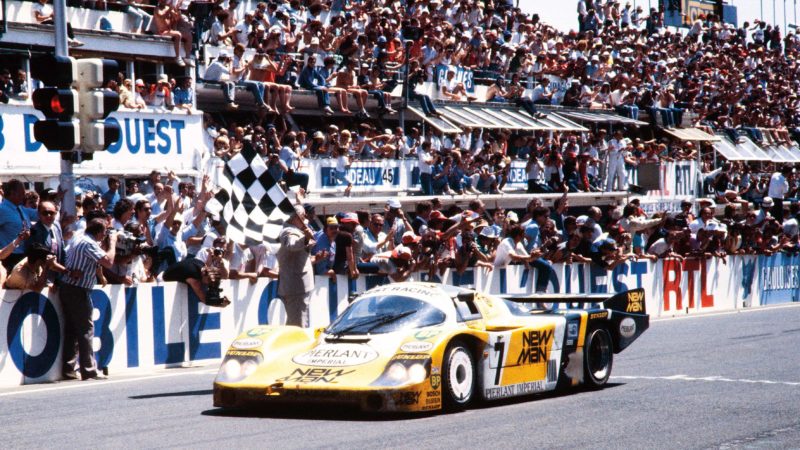

For 1984 Henri signed for Reinhold Joest’s Porsche team, sharing at Le Mans with Klaus Ludwig. “The sponsor was New Man, a French clothing firm, but I brought in Moët et Chandon with its Pierlant Imperial brand. On the grid the man from Moët was excited to see we were carrying No 7, which was his lucky number. ‘With that number, you will win,’ he said. The race started – and the first car in the pits was mine. A fuel pump problem: it took two long stops to fix it, so we were last. I thought the race was over for us, and so did my Moët friend. But Klaus and I drove like mad, and by 20:00hrs on Saturday we were 15th. By 04:00 on Sunday we were fourth. We were in the lead by 08:00, and kept it to the end.” Le Mans would never again be won by a car driven by just two drivers. In 1985 Henri drove for Lancia, bringing the turbo LC2 home seventh at Le Mans with Mauro Baldi, and for 1986 he was in Peter Sauber’s new Mercedes C8, backed by Kouros perfume.

A sensational recovery in 1984 helped Henri score his fourth, and final, Le Mans success aboard the Joest 956

Getty Images

“One of my team-mates was the New Zealander Mike Thackwell. I got on very well with Mike. We’d have long talks about what life was really about. He is a special guy. We won the Nürburgring 1000Kms together. The Sauber was good, but it used to break its transmission – like at Le Mans in ’86, when I was driving with Christian Danner and Dieter Quester.

“At Le Mans in 1987 I was with Mike and the Japanese driver Hideki Okada. After four hours, coming out of Arnage, I had a driveline failure. I nursed the car as far as the Porsche Curves, but could go no further. There was a small tool kit, and I was determined to get the car back to the pits – I am a Paris-Dakar driver, and in that event you never, ever give up. There was no radio then, but a Sauber mechanic came out on a motorbike, looked over the barrier, then rode back to the pits and told them the transmission was broken. They posted the car as a retirement. The other car had retired long before, so they cleared the pit, pulled down the door, and started loading up the truck. But I worked for a long time, and finally I managed to jam the broken driveshaft with a screwdriver. Then I drove the car gently, under its own power, back to the pit lane. At Le Mans you always remember exactly where your pit is but, because the shutter was closed, I couldn’t find it. I was completely confused. Madie was waiting for me, she was convinced I’d get the car back. She ran to the Kouros team and got them to open up the pit again. They mended it quite easily, and we were back in the race.” They raced on until 07:00hrs on Sunday when the transmission broke again, this time for good.

at home with his wife, Madie, who helps him run Pescarolo Team as it is now

Getty Images

“For 1988 Tom Walkinshaw called me to drive in the Silk Cut Jaguar team, partnered with John Watson and Raul Boesel. Jaguar won the race that year, but we were unlucky, out after 10 hours. Tom’s organisation taught me a lot: a caravan for each driver, his own medical team, all good lessons for when I ran my own team later.”

Circuit racing should supply enough excitement for most people, but Henri could never refuse a challenge, from skidoo racing in Canada in minus 52 degrees C to becoming French helicopter champion. Since the 1960s he’d done winter rallies and driven works Matras and Peugeots on the Monte Carlo Rally. Then came the Paris-Dakar. “No GPS then, no mobile phones, just a map and a compass. And no roads! Nowadays you would go to jail for organising something like that. I did it 14 times. I should have won in 1988 with Peugeot, when Jean Todt was my co-driver, but we had a big crash. The car was patched up, and we were miles behind, but we caught up. Across the Ténéré Desert we averaged 200kph. My co-driver on a lot of desert rallies was an Air France pilot, Patrick Fourticq, and we started on some air adventures.

“I was talking to a French radio station when the plane engine suddenly cut out”

We set the Paris to London record for microlights, and in 1984 we broke three records for single-engined planes: Los Angeles-New York, New York-Paris and LA-Paris. We had a Piper Malibu with everything taken out, just fuel everywhere. That whole plane was one big fuel tank. We deliberately chose the worst possible weather, a big depression over the Atlantic, so we could have a strong tail-wind. Mid-Atlantic, I was talking to a French radio station when the engine cut out. The listeners heard it. We went down, down, until we were just above the waves. The sea was terrible because of the storms; we knew if we went in we were dead. Then the engine started again. We climbed back up to our proper altitude. I don’t know what it was, maybe a fuel feed problem changing from one tank to another. But now the radio had failed, so all the people listening, who had heard our engine cutting out, believed we were dead. The journalists started writing our obituaries, but we landed at Le Bourget 14hr 2min after leaving New York.

Man in the green helmet

Getty Images

“In 1987 we tried something bigger. In 1938 Howard Hughes set a famous round-the-world record in a twin-engined Lockheed Lodestar. Patrick discovered a 1930s Lodestar in a scrapyard in Fort Lauderdale: it had been seized after smuggling drugs from Colombia. We did just enough work on it to be able to get it airborne and back across the Atlantic to France, then we rebuilt it properly. Four of us flew it: we took off three days after I’d done Le Mans, the year I’d worked to mend the Sauber’s transmission. So it was a busy week. We circled the globe in 88hr 48min, and it still stands as the piston-engined round-the-world record.”

All this time Le Mans continued to be central to Henri’s life. For Joest Porsche he was sixth in 1989, also winning the Daytona 24 Hours in 1991. In 1992 he started a long relationship with Yves Courage’s cars, and by 1996 he was racing under the banner of Elf La Filière, helping to bring on young French talent – just as he’d been brought on, more than 30 years before. In 1999, with a three-year-old Courage-Porsche, he did his final Le Mans as a driver, and his first as an entrant. With Michel Ferté and Patrice Gay, he finished a brave ninth.

From its base at Le Mans, the little Pescarolo Sport team was immediately punching above its weight. In 2000, having done an engine deal with Peugeot, Henri watched his Courage C52 finish fourth behind the dominant trio of works Audis. From 2001 there were two Pescarolo Courages at Le Mans, using first Peugeot and then Judd engines. In 2005 (Boullion/Collard/Comas), and again in 2006 (Montagny/Loeb/Hélary), Pescarolo took brilliant second places overall.

Henri has also conquered the Dakar Rally as a driver and team boss, this is his 2003 entry

Getty Images

For 2007 Henri became a fully-fledged manufacturer. The Pescarolo-Judd 01s proved very effective and finished third and fourth, beaten by just one car from each of the big-budget Audi and Peugeot teams. In 2008 three diesel Audis and three diesel Peugeots finished, but first petrol car home, in seventh, was a Pescarolo.

By now running the business was putting a heavy load on Henri. “I found at first it is not so different: instead of driving a car you drive a team. But I am only happy at the track with my cars, my drivers, my mechanics. The administration, the financial responsibility, trying to find sponsors, that is not my favourite job. And if you do not find the money, you die.

“At first Jacques Nicolet, the owner of OAK Racing, bought a majority share of the team. But in 2008 his companies were hit by the world financial crisis, and he had to pull out. Then along comes a big industrialist called Jean Py. He says, like Zorro, ‘I have come to save Pescarolo Sport!’ He took us over 100 per cent and promised to run the business, so I could concentrate on running the team. But he didn’t pay the wages, he didn’t pay the bills, and soon we were bankrupt. Everything I had built up over 10 years was gone. In October 2010 it was all put up for auction, and it seemed like the end. But Jacques Nicolet and his friend Joël Rivière, they bid for it all: the cars, the tools, the parts. They got it, and they gave it back to me, to start again. Pescarolo Sport became Pescarolo Team.”

In 2012, the old 01 scored an LMP1 third place at Sebring, and now the Pescarolo 03, based on the Aston Martin AMR-One tub but with all-new bodywork, makes its debut (budget permitting) at Le Mans. Pescarolo has also been contracted by the Japanese Dome company to run its Judd-powered car. But it’s still very hard racing against the big operators like Audi and Toyota, particularly when new regulations imposed by the Automobile Club de l’Ouest force major technological changes. It’s something about which Henri feels very strongly.

“The new regulations are a scandal. A 5-litre engine, like the Judd V10, is the most reliable and cheapest for a small team to run. Now we have to use a 3.4-litre engine, and the costs will be much greater. I proved a small team could run competitively against Audi, and then the ACO opened the race to diesels. Everybody said, ‘It’s a good idea, but be careful with the equivalence.’ The petrol engines’ power is fixed by the air intake restrictor, but it is difficult to restrict the turbo diesels in that way. We proved that the diesels had 110-150bhp more than the petrol cars. Of course Audi and Peugeot did not accept our figures. But after Peugeot withdrew, one of their technical people told me, ‘It was not in our interests to say so then, but your figures were entirely correct.’

Overseeing his team taking on the big boys at Le Mans, 2009

Getty Images

“Before 2007, I could promise my sponsors to fight for the podium. Against the diesels, all I could promise was a fight to be the first petrol finisher. The small teams – us, ORECA, Courage – we aren’t asking for it to be made easy for us to beat Audi. All we are asking for was a fair fight. And now we have the hybrids. We are expecting that to be worth at least 3sec a lap at Le Mans. For 2014 everybody is supposed to have the same amount of energy, whatever the specification, but it will be difficult for the small teams to find the hybrid technology.

“I have told the ACO: for the big teams, racing is just marketing. They can decide to leave at any time, when an accountant goes through some figures – as we have seen now, with Peugeot. For the small teams, racing is our life. It is the only thing we do. We will not stop – until we have no more money. Then we will die. If you do not look after the small teams, and they cannot afford to race any more, you no longer have a race.

“So if you ask me what is our goal, I will say: in my life I have met many challenges, and I have survived. Now Pescarolo Team, and all the small teams in endurance racing, are facing exactly that same challenge: to survive.”

With our own Simon Taylor

James Mitchell

Taken from Motor Sport July 2012