Ferrari's Le Mans glory days

Ferrari’s golden era at Le Mans helped it win seven of eight races in the ‘50s and ‘60s. Andrew Frankel examines the characters and cars behind the victories.

Getty Images

The participation of Ferrari at Le Mans started in 1949 when Ferrari the company was but two years old, though Ferrari the man was already in his fifties. But it is another man, Luigi Chinetti, who was the dominant figure in Ferrari’s early 24-hour campaigns in France. Already a double Le Mans winner (in 1932 and 1934 in Alfa Romeos), and then agent for Ferrari in France and the USA, he made it his business to establish Ferrari as one of the names in what was already regarded as one of the world’s greatest long-distance races.

“The D-type was cutting edge. The 375 was almost pre-war by comparison”

That year he drove a 166MM with Peter Mitchell-Thomson, better known as Lord Selsdon, though in truth illness prevented the latter from playing a meaningful role in the race. It was left to Chinetti, himself no spring chicken at nearly 48, to drive 22 hours solo against a field mainly comprising Delages and Delahayes with far larger engines than the little 2-litre V12 at his command. But his was a flawless performance, winning the class, the race and the Index of Performance some 17 years after his first Le Mans win, a feat to this day matched only by Hurley Haywood (1977-94) and beaten by none. Chinetti would race Ferraris in the next four Le Mans, emerging with one eighth-place finish in 1951 as his only meaningful result.

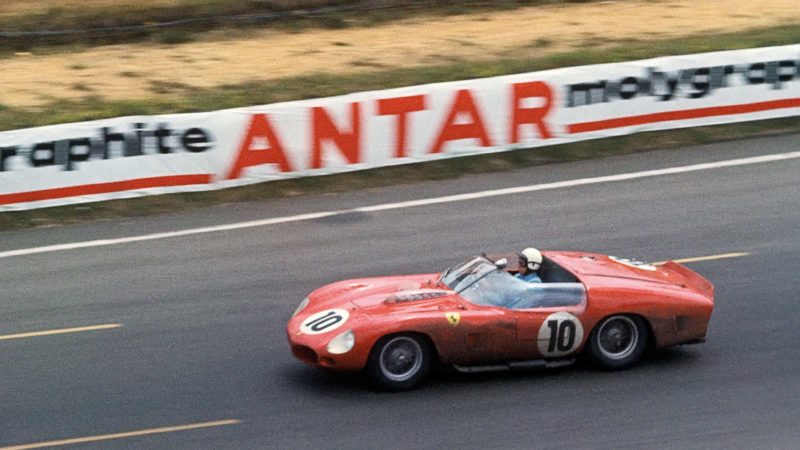

Ferrari was up against far more modern Jaguars in the early 1950s. These are the 340MMs of 1953

Peter Mitchell-Thomson and Luigi Chinetti in 1949

Getty Images

Maurice Trintignant and José Froilán González in the 375 Plus of 1954

Getty Images

The works team in the pits during the same year. Far right: Chinetti drove for 22 hours in 1949

Getty Images

Ferrari itself didn’t enter as a works team until 1952 but the performance of Ascari and Villoresi need not delay us for long here. Soon to be F1 World Champion Ascari started, led with ease, smashed the lap record and retired with a shot clutch after just three hours. The following year brought a proper works effort with three brutal 340MMs taking the start, though the dream team of Farina and Hawthorn was disqualified after less than two hours for a refuelling infringement leaving Ascari and Villoresi to make amends for the previous year. And they nearly did, duking it out with the Jaguars until, once more, the clutch failed, four hours from the end.

Only two works Ferraris entered the race in 1954, but it was enough, with González and Trintignant winning in a 5-litre 375 Plus. An easy win then, given the only opposition at the flag was the 3.4-litre Jaguar D-type of Rolt and Hamilton? Not a bit of it: the D-type was state of the art with disc brakes, cutting-edge aerodynamics and monocoque construction while the 375 was architecturally almost pre-war by comparison. Moreover its drivers had to wrestle with it throughout one of the wettest Le Mans on record up until that time. It was a victory as hard-earned as it was thoroughly deserved.

“It was only when Ford turned up with the GT40 that Ferrari had a proper fight”

There then followed a distinctly fallow period for the Scuderia: five Ferraris entered in 1955, none finished. Third place in 1956 was all that could be salvaged from six Ferraris starting while in 1957 no fewer than nine started, all prototypes, but just two were still running 24 hours later in fifth and seventh places. Few would have predicted the golden era that was about to dawn.

In the eight races held between 1958 and 1965, Ferraris won seven, beaten only by Aston Martin in 1959. Some evidence of just how bad the weather was in 1958 is provided by the fact the winning Testa Rossa of Gendebien and Phil Hill covered 22 fewer laps than the private D-type that won the year before. It was however a dominant win, coming home fully 12 laps clear of the second-place Aston Martin DB3S of the Whitehead brothers.

Olivier Gendebien was a key to Ferrari’s success. Here he is en route to victory in the 1961 250. It would be his third Le Mans win

Getty Images

A year later Gendebien would be the first driver to reach four wins, here with Phil Hill.

Getty Images

Gendebien’s first victory, during a soaked 1958 race

Getty Images

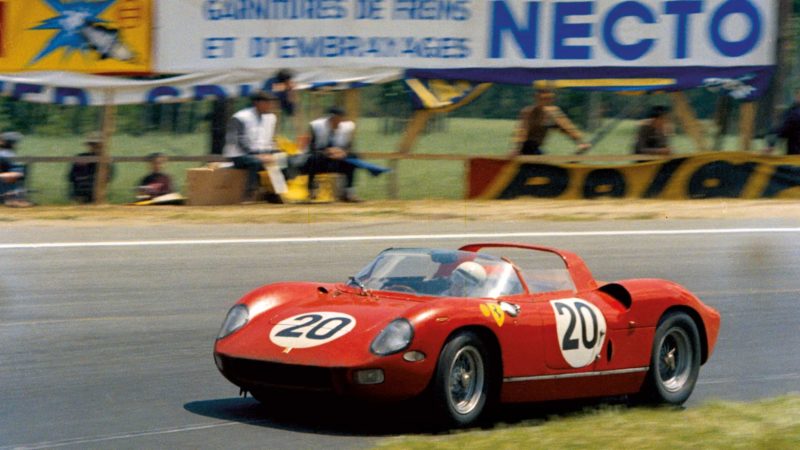

Jean Guichet and Nino Vaccarella’s 275P on its way to a fifth-straight Le Mans win for Ferrari in 1964. The Scuderia’s seven-race streak was only broken by Aston Martin in 1959

Getty Images

The races from 1960-63 brought straightforward victories against frankly thin opposition, proved by the fact that in 1962 and 1963 second place was achieved by privately entered 250GTOs, the closest to date a car from the GT category has come to winning Le Mans outright. The 1962 event was also the last time a front-engined car would win Le Mans.

“When Ferrari packed up its works team, everyone wondered when it would ever be back. Few would have bet it would take 50 years”

It was only in 1964 when Ford turned up with a handy new device called the GT40 that Ferrari found itself with a proper fight on its hands. A stunning lap by John Surtees put Ferrari on pole, but there was a Ford right next to him. In the event the Fords were too new and too fragile and they’d all retire, leaving Ferrari to lock out all three places on the podium. The only suggestion that the tide was turning was the Shelby American Daytona Coupé in fourth place, ahead of all the GTOs and breaking Ferrari’s stranglehold on the GT category. Who would have bet as the corks popped in the pits that night that Ferrari would already have recorded its last works victory at Le Mans, at least until now?

The grid lined up for the 1964 event. John Surtees had put Ferrari on pole with a superb lap in the 330P he shared with Lorenzo Bandini, but it would be the No20 275 of Nino Vaccarella/Jean Guichet that would lead an all-Ferrari podium ahead of Graham Hill/Jo Bonnier and Surtees/Bandini. At this point a Le Mans without Ferrari was unthinkable

Getty Images

I’m not going to dwell for long on the 1965 race because the failure of both the works Ferrari and Ford teams is well documented, as is the victory of the utterly unfancied NART 250LM of Rindt and Gregory and the fable of Ed Hugus doing a night time stint when no-one else was looking. But it does amuse me that the single biggest threat to the car’s win in the closing hours came from none other than Ferrari itself, possibly even Enzo Ferrari himself. The car was battling it out with an equally private Belgian LM, the biggest difference between the two being that the Belgians were on Dunlop tyres, the NART car on Goodyears, and Ferrari was contracted to Dunlop. So an emissary was sent to tell the NART team that it would be most helpful if the Dunlop-shod car be allowed to win. They reckoned without the boss of NART, who made his feelings on the subject of throwing the race to suit Ferrari very clear. That boss? None other than Luigi Chinetti, the man responsible in very large part for both Ferrari’s first and most recent Le Mans wins.

“Chinetti made his feelings clear about throwing the race to suit Ferrari”

Ferrari had no answer to the Fords for the next four years nor the Porsches in 1970 and 1971. But with the new 3-litre formula in 1972 Ferrari had a golden opportunity to return to winning ways. Its 312PB was so much better than anything else it won 10 of the 11 rounds of the championship that year and only failed in the 11th by not entering it. That race was Le Mans. Why? Essentially because Matra had taken a diametrically opposed strategy and forsaken all other races that year to focus its efforts on Le Mans alone. And it worked. Despite Ferrari being fastest at the test weekend, despite there being four 312PBs on the entry list, one week before the race they were all withdrawn, giving its rival the clear run to victory it craved.

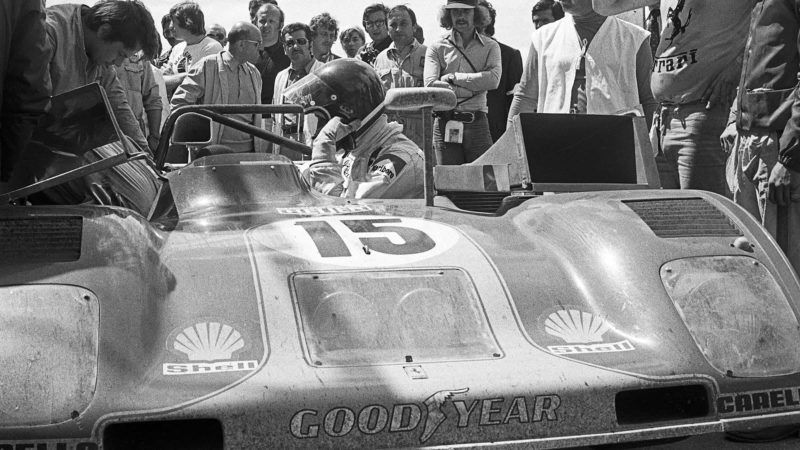

Jacky Ickx in the 312PB of 1973, the last Ferrari works entry to compete at Le Mans’ top class

Getty Images

Schenken and Reutemann’s car in action in the same race

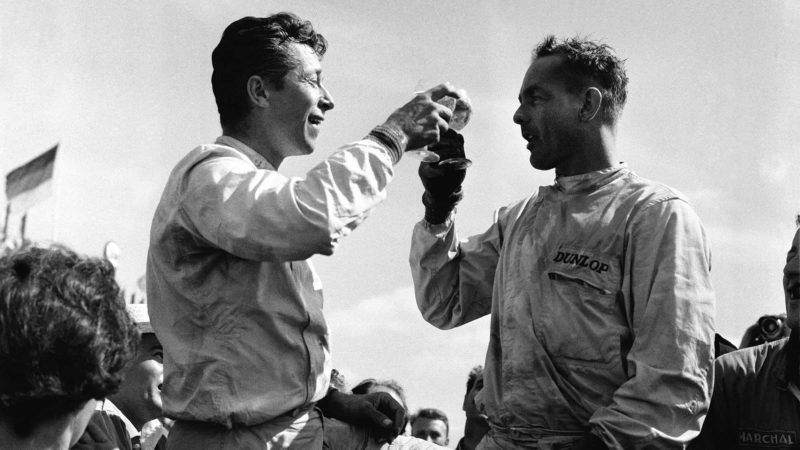

NART drivers Masten Gregory and Jochen Rindt celebrate in 1965, Ferrari’s last outright Le Mans win

By contrast, 1973 was a fine effort, promoted by the ACO as an epic battle between Matra and Ferrari on the 50th anniversary of the original running of the race. And it lived up to its billing. Ferrari certainly had the pace, the 312PBs lining up first and second on the grid with the Matras behind, but the cars proved fragile.

A wonderful night-time battle between the Ickx–Redman Ferrari and Larrousse-Pescarolo Matra ended when the Ferrari developed a fuel leak and then blew its engine fighting back through the field. By then the sister car of Reutemann and Schenken was already out with the same malady, leaving just the car of Merzario and Pace to fight the cause. And if it too had not suffered a fuel leak and the need to change the clutch maybe the outcome would have been different. In the end it merely split the surviving Matras, beating one by no fewer than 18 laps, but still six laps behind the runaway winner.

And that was it: Ferrari retired its factory sports car team and everyone wondered when it would ever be back. Few, I imagine, would have bet it would take 50 years.