The Brits are coming

Stirling Moss knew a British Grand Prix winner was close, and Jaguar’s Le Mans win in 1951 showed what was possible, even if BRM didn’t

Getty Images

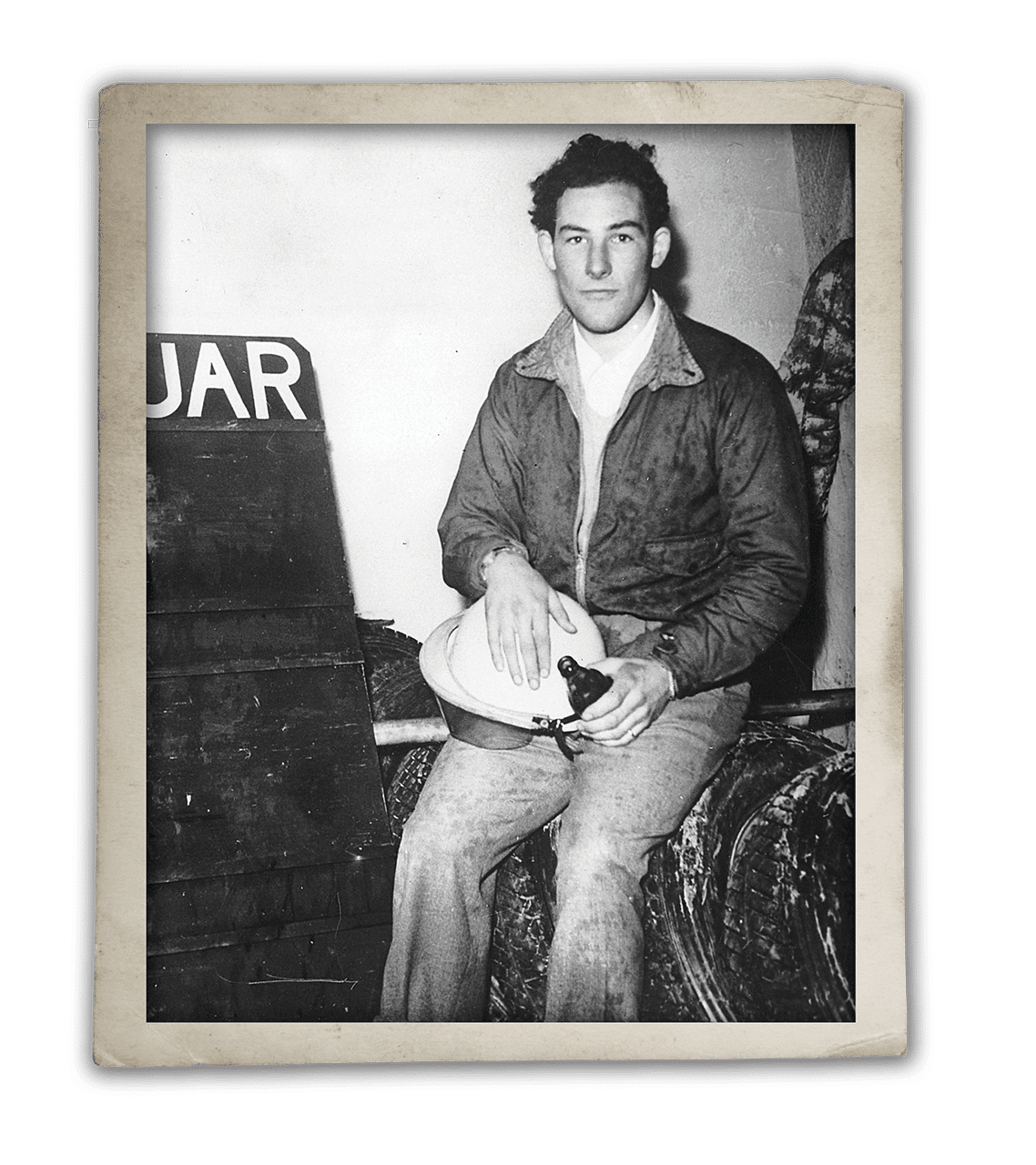

Stirling Moss preferred the C- to the D-type. The latter was tauter and faster – at Le Mans at least – but the former was more adaptable and kinder to a burgeoning career. The pride he felt as Jaguar’s secret weapon was pushed into scrutineering prior to the 24 Hours of 1951 was perhaps equalled only by his British Grand Prix victory for Vanwall at Aintree six years later.

“We really did feel as if we were showing the flag, and that counted for a lot,” said Moss.

‘The Boy’ had signed to drive for Jaguar on the eve of his 21st birthday in 1950, having proved that he could handle a ‘man’s car’ – an alloy-bodied XK120 – in the tipping Tourist Trophy rain of Dundrod. He arrived seeing no reason why Britain could not succeed on the wider stage. The C-type confirmed that. Then he drove BRM’s V16 Grand Prix challenger and began to wonder… it would remain forever the worst car he drove. In contrast to that magnificent, hugely hyped flop, Jaguar aimed lower with its C-type, and with greater accuracy and perspicacity.

The XK120-C was a spaceframe racer – albeit underpinned by that sculptural, proven in-line ‘six’ – which, unlike the BRM – a pre-war design in a post-war world – looked to the future of speed.

Aerodynamicist Malcolm Sayer created an enveloping shape as beautiful as it was efficient. Suddenly Britain found itself ahead of the French curve. When Moss, on a measured half-throttle yet still pulling 150mph-plus along the Mulsanne, breezed past the Talbot-Lago – a GP car in two-seater disguise – of José Froilán González on the opening lap, the template of that groundbreaking Le Mans was set. The beefy Argentinian squeezed back by on the brakes soon after – Jag was still on drums in 1951 – only for Moss, grinning inwardly, to breeze by once again on the run to Arnage. Moss led by a lap after two hours and headed a Jaguar 1-2-3 after four. It was too good to be true. And it was. A copper oil pipe in the sump succumbed to vibration and bearings ran dry after eight hours. The same problem had sidelined the sister car of Clemente Biondetti/Leslie Johnson four hours earlier.

That night was wet and miserable – and the Jaguar’s headlights were one of its lowlights – yet the remaining C-type greeted the dawn with an eight-lap lead. Peters Whitehead and Walker had continued to wear down opposition that included a Talbot co-driven by Juan Manuel Fangio and heroic 1950 winner Louis Rosier – plus nine Ferraris and a fleet of Chrysler V8-engined Cunninghams.

No, Moss didn’t win this Le Mans, but Jaguar did, and in doing so showed British ingenuity against much better-funded organisations. Shame then that at the time its approach wasn’t translating over to BRM. Motor Sport, still hopeful, intoned: “May the BRM follow in its [Jaguar’s] noble wheel tracks…”

Moss, drawn to the BRM V16’s siren’s song, was not blind to the car’s shortcomings, but would join Walker in racing the V16 once – his experience at Dundrod’s Ulster Trophy in June 1952 proving somewhat mentally scarring. He again put pen to paper, this time to say, ‘Thanks, but no thanks.’ Moss would spend the next year on a fruitless quest to find a British-made GP winner. Being ahead of your time can be a double-edged sword. But he was surer than ever that time was coming. For three weeks after the Ulster Trophy, back behind the wheel of his beloved C-type at Reims, he had scored the first international victory for a car fitted with disc brakes. Jaguar was pointing the way.