Jaguar shocks Le Mans with second win

Having celebrated its first victory at La Sarthe in 1951, few thought Jaguar could do it again two years later with largely the same car. Cue a record-breaking display that put the British marque’s rivals in the shade

Getty Images

The Le Mans 24 Hours carries with it more tradition and history than any other event, and the occasion of the XXIst Grand Prix d’Endurance not only continued this position, but celebrated the race’s 21st birthday by being the first when over 100mph has been averaged for the whole 24 hours. This achievement was recorded by A. P. R. Rolt and J. Duncan Hamilton driving a factory XK120-C Jaguar, averaging over 105.5mph. So fast was the pace set by the leaders that the first seven finishers all averaged over the 100mph mark.

The weeks before Le Mans were crammed with rumour and speculation as other races were watched closely to try and get a lead on which team could potentially star at La Sarthe. This year, if anyone had suggested that Jaguars would have swept the board, with the four cars starting and finishing in first, second, fourth and ninth, they would have been considered to be out of their minds. It was well known that the Coventry firm was competing with the same models it used in 1951, whereas everyone else was preparing special new cars.

Right up to the first practice there was never a suggestion that the Jaguars had a hope of winning, unless everyone else blew up. But when Moss began to put in some 4min 32sec laps, comfortably as fast as any of the opposition, it was time to think again.

“There was never a suggestion Jaguar could sweep the board”

At 1600hrs on Saturday, it was still not certain that Jaguar could be in the running, unless the opposition fought each other so furiously as to blow each other up. But 24 hours later it was a different story. Jaguars had set the pace from the fall of the flag, and led for the entirety at a speed never before realised, which caused all but two of the opposition to retire or drop right back. Jaguar had achieved the impossible not by luck or chance, but by winning the fiercest battle ever fought at Le Mans. Practice gave a good insight, with all of the factory-entered cars showing incredible speed. Watching along the Mulsanne, the speeds of the Ferrari coupés, the Lancias, Jaguars, Allards and Aston Martins were most impressive, while the two streamlined 1.5-litre Porsches were going past the Austin-Healeys with ease. Many drivers believed they were doing 160-170mph, but a roadside calculation suggested that the really fast cars were travelling nearer 130mph. During the race the answer was given by official timing over a flying kilometre, when the fastest proved to be the Cunningham with 248.2kph (154mph), followed by the Alfa-Romeos with 245kph, Ferrari with 239kph and Allard with 234kph: as the local paper said, “not as fast as the claims, but quite fast enough anyway.”

At Mulsanne corner the impression was one of immense acceleration by the 4.1-litre Ferraris, unbelievable braking power on the Jaguars – Moss in particular – and the high cornering speeds of the little French cars, such as the Renaults, DBs and Gordinis.

Times in practice do not count for anything, except perhaps to demoralise the opposition; as the starting grid is arranged on capacity, a supercharged car doubling its normal capacity for this purpose.

Between midday and 1600hrs on Saturday the cars began to form up, with full tanks, fillers sealed and all spares and tools loaded. Passenger seats contained boxes of spares, jacks, tools, shovels and anything else that might be needed.

At the top of the line of 60 cars was the old supercharged 4.5-litre Talbot of Chambas-Cortanze, then came the three Cunninghams, Briggs himself and Spear driving one of last year’s open two-seaters, Walters/Fitch with the new two-seater and Moran/Bennett with last year’s coupé. All three were using the V8 Chrysler Firepower engines. Painted in blue and white and supported by a large pit staff and even larger overpowering mobile workshop; it really did seem that it was time Cunningham received a win in return for his money.

Moss talks with Jaguar team manager Lofty England in the pits

The three olive-green works Jaguars were, to all intents and purposes, identical to the 1951 cars. These were driven by Moss-Walker, RoIt–Hamilton and Whitehead– Stewart. The major changes on the Jaguars were the fitting of three double-choke Weber carburettors drawing air from a sealed box fed by a bonnet-top scoop, and the adoption of disc brakes. Whilst changing from SD to Weber carbs the characteristics of the power curve had been extensively modified to give a much wider and more useful rev range, far more power in the middle of the curve, thus giving better pick-up and keeping the peak about the same. Added to this was the effect of the disc brakes, operated by Girling booster mechanisms, which gave greater braking power and almost indefinite life and efficiency, with the result that lap times were reduced enormously with virtually no increase to the car’s top speed. With the improved power curve the Jaguar was obviously spending more time at its top speed than some of the faster cars, which took longer to reach their maximum.

“It did not seem possible that Jaguar could keep up this pace”

The performance of these revised Jaguars was a perfect example of the simple maxim that speed is a question of time and distance, not miles per hour.

At 1600hrs the flag fell and the field set off in a free-for-all race. Moss and Parnell both made good starts from positions way down the line, obviously out to set the pace for their respective teams, as was Villoresi. At the end of the first lap there was a strong impression that everyone was soft-pedalling and trying not to go too fast and Allard led the field, which was closely bunched among the faster cars. The first few laps at Le Mans mean very little and it was not until the end of the first half-hour that the picture became clearer. Rolt had put in a record lap at 173.667kph, Moss was leading the field, closely followed by Villoresi, Cole, Rolt, Fitch, Kling, Fangio, Sanesi and Hawthorn.

Early action in the Esses: the Cunningham of Charles Moran and John Gordon Bennett leads the Ferrari 375MM Berlinetta of Alberto Ascari and Luigi Villoresi and the Jaguar C-type of Stirling Moss

Getty Images

At first it was thought that the Italian Alfa-Romeo and Ferrari cars would battle each other in a delightful demonstration of Latin excitement, but it was not so. The Alfa-Romeos were clearly playing a waiting game, running in close formation, Fitch and Walters with the new Cunningham were being pacemakers, while Cole was running a lone race. Allard didn’t last long and retired after only four laps with a collapsed rear suspension that severed a brake pipe, and Hawthorn’s Ferrari 340MM came in with a loose brake pipe, but not before he had raised the lap-record to 174.160kph. Rolt pushed this up to 174.905kph, before Kling was timed at 245.065kph.

By 1700hrs the order had settled down, although the average speed was enormous, over 175 kilometres being covered in the first hour by Moss, who had built a useful lead. It was now clear that Jaguar really was a force to be reckoned with. Ferrari and Alfa-Romeo were also in the hunt, but the Talbots and Lancias were quite outclassed, as were the Aston Martins. The lap record continued to fall, while the Ferrari pit forgot the regulations and topped up Hawthorn’s brake system with fluid before the specified 28 laps, thereby being disqualified.

A streamlined Porsche streaks past a crashed Talbot-Lago

Getty Images

Moss dropped the lead to Villoresi’s Ferrari and came in for a plug change. Rolt made up for Moss’ stop by taking the lead at 1800hrs. The pace was still fantastic and it was Jaguar setting it, causing the Italians to press their machinery hard. By 1900hrs, the Rolt-Hamilton Jaguar led the Ascari-Villoresi Ferrari, followed by Cole-Chinetti, Sanesi-Carini, Kling-Riess. Already the first five cars were two laps clear of the rest.

Hamilton took over from Rolt and lapped steadily in 4min 35sec – five seconds faster than last year’s record and a speed of 176.623kph, while Moss stopped again for plugs and then discovered the fouling was being caused by a dirty fuel filter; this was removed and the car then went properly again, he and Walker setting about getting back among the leaders.

As darkness approached the Ferrari-Jaguar battle continued unabated, between the teams Ascari-Villoresi and Rolt-Hamilton with the Alfa-Romeo not far behind. By 2100hrs, 15 cars had already dropped out and with pit-stops and changes of drivers the order underwent a shuffle, though Rolt and Hamilton were still well in the lead. Following were the two Alfa-Romeos – Kling-Riess and Sanesi-Carini – followed by the Ferrari of Ascari-Villoresi, the Cunningham of Fitch-Walters, and the Jaguar of Whitehead-Stewart, all on the same lap.

Cars dropped out regularly due to the fierce pace.

Through the early hours of the night the Jaguar pace continued with little slackening, lapping at 4min 46sec in the darkness, and still the Ferrari of Ascari-Villoresi hounded their heels, occasionally taking the lead during pit stops, while the two Alfa-Romeos were third and fourth, content to sit and wait. The Moss-Walker Jaguar was gaining and by 0100hrs was back into seventh.

“Cars fell by the wayside often, but not the ones from Coventry”

The speed and endurance of the Jaguars was nothing short of remarkable and the consistency with which Rolt-Hamilton circulated, with laps as quick as 4min 37sec, was unbelievable. They were still in the lead on both distance and handicap through the small hours of the morning and showed no signs of tiring while the rival Ferrari was now losing ground, handicapped by a clutch problem. By 0300hrs another Alfa-Romeo was out, when the Sanesi-Carini car had its rear suspension collapse, yet still the Jaguars went on, with Whitehead-Stewart now in fifth behind the Fitch-Walters Cunningham.

By now the field was reduced to 32 runners and if the pace did not slacken it looked as though many more would fall, for it did not seem possible that the Jaguars could continue at this mad pace. But continue they did, and cars fell by the wayside at frequent intervals, but not the Coventry products, they just went on and on, never missing a beat. The last Alfa-Romeo was withdrawn when something unexplainable stopped it and there was disaster at Bristol when its No.38 450 Coupé burst its engine, causing a major fire in the cockpit which burnt Wisdom rather badly.

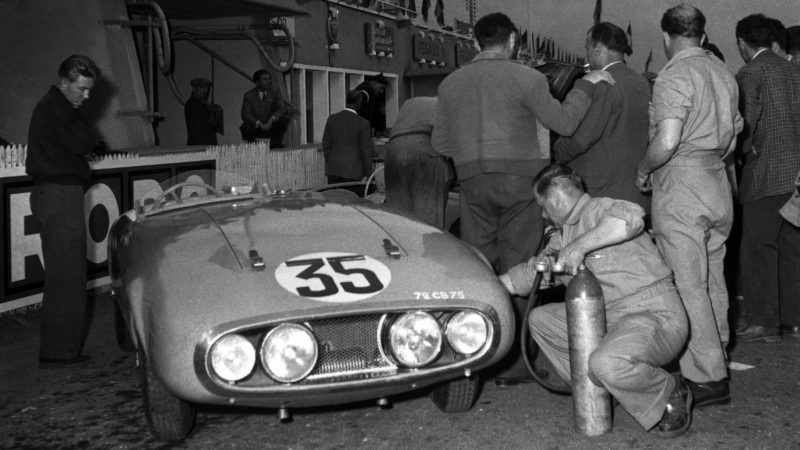

Preparation in the pits before the start

Getty Images

Although the Ascari-Villoresi car was still putting up a fight to Jaguar, it was very lame, for the clutch would not free at all and it was using a lot of water. After each pit stop it had to be driven off on the starter in bottom gear until the engine fired and once or twice it nearly failed; especially after Ascari had left all lamps ablaze during a stop! However, in a win-or-burst attempt it was driven hard the whole time, but it had no effect at all on the remarkable Jaguar of Rolt and Hamilton that now had a full lap’s lead, and was still leading on handicap, which was a remarkable feat that caused the French to check their sums.

The night had been clear, but some damp mist hung as dawn approached, leading to tiring conditions for the drivers. Hamilton handed over to Rolt with the remark that he had just had the worst three hours of driving he had ever known. Their windscreen had been smashed early in the race and both were suffering from wind-buffeting, but kept up the pace, with an average speed of well over 170kph (105mph).

At dawn all the Jaguars came in for routine stops, for fuel, oil and tyres and there was a moment’s consternation when the Ecurie Francorchamps C-type stopped to investigate a loose plug just as the pits were preparing to receive Walker, who was making up time fast and due to hand over to Moss. The yellow car was put right and quickly shooed off, to the surprise of driver Roger Laurent, who was unaware of the fast-approaching works car. In reasonably quick time Moss was away, though the pit work was not as smooth and confident as one would like to see; it was quick enough but lacked the certainty of the Ferrari team. The Jaguar team was controlled by two signboards, one indicating faster, steady, slower or come-in by a clear movable arrow, the other giving lap times, illuminated at night by a hand-directed flood-light.

Duncan Hamilton swigs champagne alongside Tony Rolt as they celebrate their record-breaking victory at Le Mans

Ferrari had an impressive single-piece self-illuminating sign, like an advertisement hoarding, in the centre of which was a square containing the Ferrari ‘horse’ with a light behind it which flashed on and off.

By the time the morning mists had cleared and the Jaguar pit was full of frying eggs and bacon, Rolt and Hamilton were still a lap ahead of the lame Ferrari, which was nevertheless still going hard; three laps behind came the Fitch-Walters Cunningham a lap ahead of the Jaguars of Moss-Walker and Whitehead-Stewart. While everyone not driving was contemplating breakfast, a regrettable disaster happened at White House when Cole crashed in his Ferrari and was killed instantly. Still the leading Jaguar kept up the pace, now supported by the Moss-Walker car that was creeping up.

Shortly after 0830hrs there was much excitement when the leading Jaguar and the leading Ferrari both made refuelling stops at the same time, while Moss moved up another place when the leading Cunningham came in for fuel. At 0900hrs 31 runners remained and by mid-morning the sick Ferrari was dropping back fast, now in fifth due to unexpected stops for the clutch.

“Jaguar can’t get complacent, but it can enjoy a superb success”

Rolt and Hamilton were now way out in front, but they could not ease up as the leading Cunningham was now beginning to heap on the coal and challenge the Moss-Walker Jaguar for second. Just how hard it was trying was seen by its speed over the flying kilometre which went up to a record of first 246 and then 248kph, but Jaguar was still in full command. The sick Ferrari was finally withdrawn at 1100hrs, leaving only the Marzottos’ car left to challenge the English-speaking teams, but it was in fifth.

Normally the leading car can afford to slow up by midday on Sunday, but with the Cunningham still pressing hard in third place, the two leading Jaguars were kept going at a seemingly impossible speed. With three hours to go the pace slackened a little, but the average was still not far short of last year’s lap record.

The order didn’t change over the closing hours, with the Jaguars’ pace enough to thwart the late threats of the Cunningham. As Hamilton took over to complete the last stage of the race he was followed by Moss, Fitch, Stewart and Giannino Marzotto.

As the leaders started the last hour, both Jaguars and the Cunningham began to have their bonnets split, due to fastening catches breaking and Moss stopped to tear a piece of his clean away, as did the leading Cunningham, while Stewart looked to be in danger of losing the whole of the side of his bonnet. All the cars were still sounding healthy and were lapping at over 100mph. When 1600hrs arrived the whole Jaguar organisation relaxed, sure in the knowledge that it had cracked up the whole of the Continental opposition with a two-year-old car and had more than made up for the debacle of last year and its Mille Miglia retirements.

It had been an Anglo-American victory in a most outstanding manner, and while Jaguar cannot afford to become complacent, it can enjoy a wonderful success, won after one of the fiercest battles Le Mans has ever witnessed.