F1 snore-fest shows new cars badly needed: Up/Down Japanese GP

The 2025 Japanese GP showed a much more extreme change than next year's technical regulations is needed to make racing at classic F1 tracks interesting

How one of Aston Martin’s most iconic modern cars came to be, via Jaguar

You may know the story of the Jaguar that was turned into a Porsche and went on to win Le Mans not once, but twice in succession. If not, the tale of how a tub of designed by Tom Walkinshaw Racing for the Jaguar XJR-14 went on to a double win in France as the Porsche WSC95, having also spent some time betwixt as a Mazda, is one of the great racing stories. Consider the amount of time elapsed from the XJR-14’s race debut in 1991 to the WSC95’s last win in 1997, and that that final win was achieved not with the involvement or support of the Porsche factory, rather its steadfast opposition. Porsche not wanting a Porsche to win Le Mans? You read that right: if Porsche had had its way, the 1997 24 Hours of Le Mans would have been won by a McLaren…

But that’s another story for another time. For now a tale from the same period, also involving Jaguar and Walkinshaw but this time from the road car arena. I’d heard it before but never in the detail provided to me last week by one of its principal protagonists, Ian Callum, as he addressed the Aston Martin Owner’s Club at the annual Walter Hayes Memorial Lecture at the Royal Automobile Club.

Even Callum’s presence at an Aston event was, shall we say, a little surprising given he is now head of design at Jaguar. The companies were once related through Ford but have been apart for years. Imagine Adrian Newey turning up to give a talk to a room full of McLaren fans.

Except Callum and Aston have history through Tom Walkinshaw. Indeed the design language used to this day by all Aston Martins is evolved from that originated by Callum some 25 years ago. The car that wore it originally was called the DB7 and the first thing I learned was that before the DB7, Callum had never designed an entire car by himself. So not a bad way to open your account.

The second thing I didn’t know is that he wasn’t meant to do it at all: the job had originally been earmarked for Peter Stevens, who turned out to be otherwise engaged doing another handy slice of mid-1990s British sports car exotica called the McLaren F1. Thirdly, I had no idea Walkinshaw’s ultimate, unrealised aim was to start a car brand of his own.

His idea was to re-body the Jaguar XJS. It was a design he knew, liked and, after seasons of racing it culminating in victory in the European Touring Car Championship, trusted. In the meantime Jaguar had itself been struggling to replace the XJS, and had got a brand new car codenamed XJ41 to the point of production before Ford bought the company, took one look at the overweight, over budget and over time project and killed it stone dead. So using only his own money, Walkinshaw got Callum to adapt the XJ41 to fit the XJS platform and pitched the result, conceived in a fraction of the time and cost, back at Jaguar. Who didn’t like it.

At this stage Aston Martin boss Walter Hayes enters the story. Like Jaguar, Aston Martin was now owned by Ford, but unlike Jaguar, Ford had little interest in the tiny sports car manufacturer for whom profits were near mythical occurrences. Ford’s CFO at the time called the company Austin Martin. Hayes knew Aston Martin’s future depended on producing a car that would get the attention of the big bosses back in Detroit and Walkinshaw had a rejected design for a new sports car on his hands. So it didn’t take much to work out what to do next. Without telling Jaguar, Walkinshaw took Callum’s XJS-based coupe to Hayes and told him it was the car that could save Aston Martin. And Hayes agreed.

“It was a make or break car,” Callum confirms, “both for Aston Martin and me.” And because money and time remained tight, he just raided the Ford parts bin for everything that would fit. He took the tail-lights from a Mazda 323F, the door handles from a 323 estate, “because Walter wanted chrome handles and they were the only ones in the whole Ford empire.” The front indicators came from the MX-5 and the interior door mirror switches from the Ford Scorpio. Only the exterior door mirrors came from elsewhere. “We took them from the Citroen CX because they were the only mirrors that looked really cool we could afford.”

Though no one said so at the time, there was so much XJS in the DB7 it retained the same seat frames and even the structural elements of the steering wheel. But even when the car was finished, it was still not approved by Ford.

Then two things happened. On January 1 1993, Jac Nasser was appointed chairman of Ford of Europe and he was and remains a true car guy, the antithesis of the Dearborn bean counters. Then Aston Martin took the car, still without a green light to its name, to the Geneva Motor Show where it was received like its grand-father, the Jaguar E-type, had been 32 years earlier. The whole car had cost $30 million, about the price of a minor, entirely cosmetic face-lift today. Callum calls it ‘my happy car’ and if you look at it and its legacy, you can see why.

Before Callum joined Jaguar full time, he’d designed the Vanquish, the DB9 and laid out the hard points of the V8 Vantage which, I was surprised to learn, was originally intended to be mid-engined. But then Ulrich Bez joined the company and killed the idea, choosing the economically more sensible route of spinning both cars off the same platform.

So that’s how a Jaguar became an Aston Martin. But how did it become a Jaguar again? Simply because the DB7 persuaded Jaguar that there was indeed life left in the XJS platform after all, so it did its own comprehensive re-skin and called the result the XK8. It stayed in production until 2006, extending the life of the XJS platform to over 30 years. Or put another way, more than twice as long as that managed by the iconic E-type before it.

The 2025 Japanese GP showed a much more extreme change than next year's technical regulations is needed to make racing at classic F1 tracks interesting

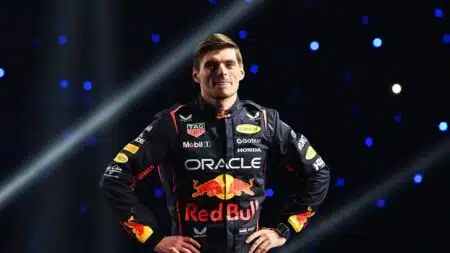

Max Verstappen looks set to be pitched into a hectic, high-stakes battle for F1 victories in 2025, between at least four teams. How will fans react if he resorts to his trademark strongman tactics?

Red Bull has a new team-mate for Max Verstappen in 2025 – punchy F1 firebrand Liam Lawson could finally be the raw racer it needs in the second seat

The 2024 F1 season was one of the wildest every seen, for on-track action and behind-the-scenes intrigue – James Elson predicts how 2025 could go even further