The mirror took the place of the riding ‘mechanic’, as was typical at the time – and the car showed winning pace.

Though the WASP may look large and ungainly today, at the time its single-seater ‘fuselage’ body was innovative through its relative aerodynamic nature – a winning margin of 1min 43sec of Ralph Mulford’s Lozier proved as much.

With motor sport history starting as it meant to go on, competitors protested the Wasp, out of fear for its speed, but on the grounds of the apparent speed of the single-seater approach – but to no avail.

“With no one to warn him of overtaking cars, they claimed Harroun would be a menace on the course,” Motor Sport wrote in 2001.

He and relief driver Cyrus Patschke, whose mid-race burst of pace helped secure the win, were indeed – but only in the sporting sense as they claimed the first ever Indy 500 with a new innovation to boot.

Miller Special: The first rear-engined IndyCar

Over two decades before Jack Brabham shocked the IndyCar grid by setting the pace in his little rear-engined Cooper-Climax T54, innovative Henry Miller’s rear-engined machine became the first such prototype to make the 500 field, piloted by George Bailey in 1938.

The creative Miller saw a wide number of groundbreaking technologies make their debut at The Brickyard, including front and four-wheel drive, but it was rear-engined innovation which had the lasting effect.

Bailey would qualify the car sixth. Though he only lasted 46 laps, this was the furthest anyone of Miller’s several ‘back-to-front’ cars would go – until ‘Black Jack’ came along.

Jack Brabham’s rear-engined Cooper T54

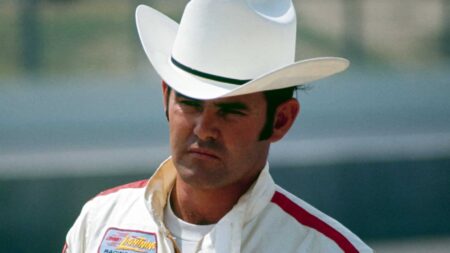

Brabham T45 – not to AJ Foyt’s tastes

Getty Images

While it may not have been the first rear-engined car to race at Indy, Brabham’s Cooper-Climax caused even more of a stir – mainly due to the results it garnered on track.