“He was a very smooth driver and had a very good brain on him, especially for the 500s. He knew how to pace himself.”

In fact, Unser won four 500s in a row, the 1977 Ontario marathon having also fallen under his spell. So, too, had the 1976 Pocono race: the maiden victory for the Cosworth DFX variant pioneered by VPJ.

“I first worked with him in 1975 at Vel’s Parnelli Jones Racing,” says Absalom.

“I tended to be a little bit guarded having been in motor racing since the middle 1960s, when we were knocking them off left, right and centre: Jimmy, Mike Spence, Jochen Rindt, and all those other guys. You had this inbuilt protection system that stopped you from becoming too close to drivers.

“But I let this slip with Al.

“The most honourable and honest person you could ever meet in this world, he was probably my best friend ever.

“Luckily, we only had one big accident while we worked together.”

That occurred early in 1978 on the high banks of Texas World Speedway – and caused Unser to miss the race at Trenton, New Jersey, immediately prior to Indianapolis.

“Something possibly broke,” says Absalom. “The thing went up against the fence and his head kissed the outside wall. It knocked him a little goofy for about two weeks.

“So he went straight into Indy, where he was still nowhere near back to his normal self; and even though he won all three 500s in it, he remained very apprehensive about that car.”

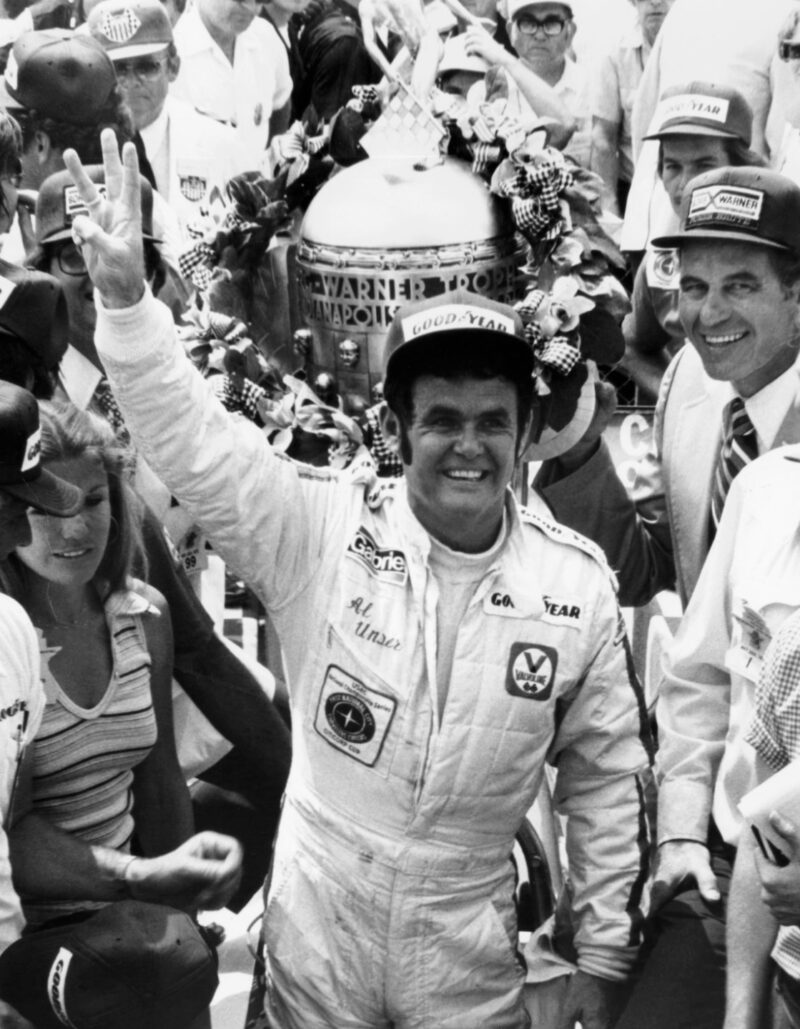

Unser celebrates in ’78 at Indianapolis

National Motor Museum/Heritage Images/Getty Images)

Unser finished second in that season’s USAC final standings having failed to add to his three keynote victories. (Champion Tom Sneva was win-less with Penske.)

“We weren’t that far off on the short tracks but always seemed to have some kind of dilemma,” says Absalom. “That T500 was probably not the greatest race car of all time, as I am sure [designer] Eric Broadley would agree, but we just hit it off at the 500s. We seemed to land at the right place and then make the car faster as those races went on.

“In a 500-miler in those days you had maybe eight pit stops and so you were able to, indeed needed to, make adjustments – tyre stagger, aero, etc – as the track evolved.

“We had a two-way radio – of sorts! – but really I could pre-empt Al, without outguessing him, in terms of what he wanted.

“It was one of those things. It’s about having confidence in each other.

“Indy? It just happens sometimes. If you are lucky enough to win, okay, it’s very nice. But to win all three was very much more of a planned project.

“We were a small operation – six full-time staff and a couple of weekend warriors, and that includes us doing the engines, too – and though we had our own test track down in Midland [Texas], we couldn’t go there between every race because of the distances involved.

“Ability-wise, Al could have done Formula 1. But his mental structure was not geared up to travel the world.”

“But we did a reasonable amount of updates and made the car a lot better than it had been when it first turned up.

“There was a lot of pressure on us to win that third 500 and yet we managed to get it done without too much drama.

“There was no one magic ingredient… though maybe Al would be the biggest one.

“Whereas his brother Bobby would want to take everything apart and analyse it all, Al relied more on his natural ability than the engineering side of being a racing driver. He’d tell you what the car was doing and let you sort it.

“He had great feel. We had adjustable anti-roll bars on the Lola and at one section of that Indy 500 he would adjust them twice every lap: full stiff for turns One and Two and then back them off.

“I worked with Mario Andretti as well. Chaparral was also running a Formula 5000 team [of Lolas] and Mario would go out and turn a lap at Riverside or wherever and be miles quicker; Al just couldn’t get the hang of it.

“But then they would readjust the car to Al’s liking and he would go faster than Mario. Then Mario would say that he wanted Al’s set-up on the car and go even quicker again.

“Ability-wise? Yes, Al could have done Formula 1. But his mental structure was not geared up to move from Albuquerque to travel the world.

“He was very much a homely kind of guy. He wouldn’t have lasted travelling all over the place, I don’t think. It wouldn’t have worked out for him. Not like it did for Mario.

“But I rated Al as the best for Indycars.”