Denis Jenkinson's Porsche 356 roars again at Goodwood

Six decades after Motor Sport's famous continental correspondent Denis Jenkinson ran his Porsche 356 across Europe, it's now racing again following a long and careful restoration

Pioneers of motor sport, the Black American Racers was a team formed of African American drivers and engineers that aimed to compete against the odds

Leonard W. Miller, an African American, was raised in Philadelphia during America’s Great Depression and World War II eras. And he was to make history in motor sport. The only thing is, not many people know this story.

Watching Duesenbergs, Auburns and Packards participate in holiday parades spawned a passion for automobiles when he was five years old, and when he reached his teenage years, he evolved as a partaker in America’s explosive car culture. Miller was drawn to the initial volumes of Hot Rod magazine and others sprouting on local newsstands. America’s passion for motor racing was booming; Miller’s too.

Eventually, Miller (above) purchased a 1940 Ford Club Coupe convertible (below) in 1952 in Pennsylvania, with a vision to convert the coupé into a hot rod. With money he earned from a summer job at a lumberyard, loading wood onto a cargo train, he built that hot rod.

The coupé was outfitted with a 1948 Mercury motor, Lincoln transmission sporting Zephyr gears and other aftermarket parts like a Tattersfield intake manifold, dual Smithy mufflers and a Buick speedometer with a dial that went past 100mph.

As the sole African American teenager that owned a hot rod in a radius of more than 50 miles around his home of West Conshohocken, Pennsylvania, Miller turned heads.

“I took a friend, Daisey Thomas, after church, on the turnpike and she became tense as I shifted through the gears toward 100 miles an hour,” recalls Miller, who’s now 85. “We hit close to 120mph before I backed off. And I’m talking about the days before seatbelts and airbags!” he says.

His peers were intrigued by the hot rod, which Miller tested on a makeshift drag strip formed out of an unopened section of the Pennsylvania Turnpike – a highway that stretches across the state – on the smooth, untouched concrete.

In 1954, things got just a little more serious and Miller was provoked into a street race by a good ol’ boy at an Esso gas station in Essex County, in the heart of segregated Virginia. Miller says he embarrassed the driver of that 1949 Ford hot rod, the good ol’ boy’s friends gawking at the two Fords streaking past the gas station, shouting repulsive slurs. They were stunned that Miller won the race; Miller was adamant to prove that he could hold his own.

They had never witnessed a confident African American, let alone one driving a hot rod that was so advanced.

The 1960s approached and Miller, now married with two children and having completed his drafted service in the United States Army, was working as a senior research scientist at New York University. Miller had an NHRA (National Hot Rod Association) ‘automatic class’ drag racer: a 1963 Volvo P-1800 modified to street legal standards.

The Volvo was prepared by Tony Hill, a British engineer who had moved to New Jersey from the UK and the car earned Miller numerous wins at the Vargo Dragway in Pennsylvania.

And at the boiling point of America’s civil rights movement, drag racing afforded Miller sanctuary from the stresses surrounding his own life as an African American. The mayhem of Martin Luther King’s assassination and the aftershocks raged on.

At the end of the 1960s, on the backdrop of an America that was suffering record numbers of casualties in Vietnam, motor racing was reaching its zenith. Miller befriended another famous African American driver – Wendell Scott – at the Trenton International Speedway and Scott attempted to convince the drag racer to form an African American NASCAR team.

More: Changing of the old guard: the story of Wendell Scott and Bubba Wallace

That meeting with Scott planted seeds in Miller’s mind. But Scott warned him away from NASCAR. “Road racing is fancier than stock cars, but it is going to burn a bigger hole in your pocket,” he said.

In 1969, Miller created Miller Brothers Racing, which would compete in NHRA racing with a 1955 Chevrolet station wagon, powered by an inline-six cylinder engine modified with parts from a shop in Southern California.

Taking parts from his Chevrolet on the train from Trenton, New Jersey, up to a carburettor shop in Harlem, New York City, Miller managed to outfit the Chevrolet station wagon (below) with a custom part from a Jaguar, the part modified by British mechanics to fit the station wagon.

His brother, Dexter Miller, attached the parts when Leonard moved back to New Jersey and a childhood friend, Kenneth Wright, was summoned to drive. Wright was another African American hot rodder and drag racer. His record – 38 victories in New Jersey – propelled Miller Brothers Racing to local fame as it won the fourth State Championship at Atco Dragway at the end of the 1960s.

NASCAR driver Scott introduced Miller to African American United States Auto Club official, Mel Leighton, who persuaded the Miller Brothers Racing Owner to assemble a road racing team with second generation African American racing driver Benny Scott (no relation to Wendell) at the wheel.

“Early in the meeting, Benny told me, ‘I’m ready to go with you thick or thin,’” says Miller. “In other words, like me, Benny was willing to bet the farm if our money became too tenuous to support ourselves in road racing.”

Miller flew to Los Angeles to meet Benny and created Vanguard Racing, entering SCCA (Sports Car Club of America) Formula A and Formula 5000 races with a Chevrolet V8-powered McLaren M10A, racing at the likes of Watkins Glen, Laguna Seca and Riverside on their way to the 1972 Formula A Southern Pacific Division Championship.

Small sponsorships followed, and white driver John Mahler qualified the team’s McLaren M15A in the 1972 Indianapolis 500. Vanguard’s real objective was to forge a path for Benny to race, but there just wasn’t enough sponsorship offered to African American businessmen for it to sustain the McLarens for the following season.

So Miller reorganised in 1973 and created Black American Racers, Inc. (BAR), developing a less costly Formula Super Vee team with driver Benny in a Lola T-252. Miller also recruited Coyle Peek, an African American driver from New York to be developed as a backup driver.

Miller dispatched Peek to England to compete with a Royale RP16, Formula Ford powered by a Scholar 1600cc motor at Brands Hatch, Mallory Park, and Silverstone.

“Peek was apprehensive to travel across the North Atlantic to England. I learned days before his departure that he had never flown on an aeroplane,” Miller recalls.

Miller’s office had a bank of analog clocks on the wall representing all four time zones in the contiguous United States and a fifth clock labelled London. “I glanced at the time in London and telephoned Peter Semus, with whom I established a relationship to facilitate Coyle Peek’s Formula Ford competition.

“I put Peek on the phone with Semus to offer Peek reassurance.”

It was the expertise of Ronald Hines, another African American hot rodder, that helped BAR become a driving force. Hines was employed as chief engineer for the team.

“In the late 1950s, my dormitory roommate, John Cox was from Terre Haute, Indiana and let me read his Rod & Custom magazine featuring a 1934 Ford Coupe,” Hines recalls, smiling.

“That’s how I became hooked on old Ford coupe hot rods.”

Hines was a mechanical engineer graduate from the University of Pennsylvania and had also served as an officer in the United States Army National Guard.

With childhood friend Wright, a Temple University graduate, who was a United States Navy Reservist, Miller garnered enough funding from their personal savings to compete in Formula Super Vee in 1973. BAR was about to take to the track in anger.

Apprehensive as Peek was, Miller had created something unique against the odds: in the gladiatorial sport of motor racing, the Black American Racers became the first African American-run racing team, and perhaps the only one ever.

Leonard T. Miller is the co-author of Racing While Black: How An African-American Stock Car Team Made Its Mark On NASCAR

Six decades after Motor Sport's famous continental correspondent Denis Jenkinson ran his Porsche 356 across Europe, it's now racing again following a long and careful restoration

Voice of 90’s motor racing is completing project to revive hidden gems of motor sport film and television.

Ferrari's F1 car is set to feature a 'blue livery' at the 2024 Miami GP – we look back on the other times Maranello cars haven't run in red

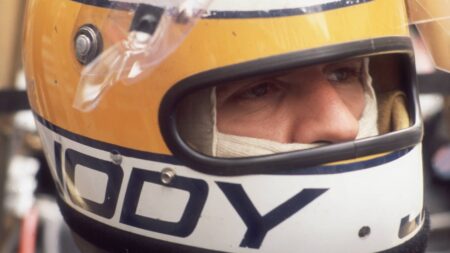

Think of the great Formula 1 champions and Jody Scheckter is unlikely to feature. But, writes Matt Bishop, the 1979 title-winner deserves more acclaim for a career in which he was once the best driver, bar none