Learning English in school – he now speaks the language fluently – gave him access to British publications. But he wasn’t able to find much detailed information about American racing until two decades ago, when he discovered the statistics collected by Phil Harms.

A Boeing engineer and avid motorsports fan, Harms amassed 10,000 photos and compiled a database of race results stretching back to the 1890s. Ferner was fascinated by what he found – but also by what was missing. Harms had focused on major-league events. But during the Depression, the AAA Contest Board National Championship, as IndyCar racing was known back then, was limited to a handful of races. In 1938, for example, there were only two on the schedule – Indy and a 100-miler on the dirt at Syracuse.

“I realised there had to be more races, and I wanted to know where the rest of the history was,” Ferner says. “If I had known how deep that foxhole was, maybe I wouldn’t have dared to start digging. But once I got my nose in, I dug deeper and deeper and – wow! There’s probably tenfold as much racing in America as there is in the rest of the world. So there’s a lot of history that still needs to be found.”

“Ernie Triplett is very much under-appreciated. He’s been completely forgotten but he was a superstar in the ’30s.”

Ironically, Ferner isn’t the first European motorsports historian to focus his attention almost exclusively on the United States. Donald Davidson, an Englishman expat, spent 23 years as the official historian of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway before retiring last year. But whereas Davidson was a master of the memorable anecdote, Ferner favours a more analytical approach.

Fortunately, he began his project around the time that the awesome power of the internet as a research tool was first becoming apparent. This allowed him to tap into online databases collating digitised copies of thousands of American newspapers, large and small, from coast to coast. Although he originally planned to track only sprint car races, he eventually widened his net to include midgets.

By searching for drivers, cars and tracks, he was able to identify scores of races that weren’t in the Harms database. And while Ferner is the first to admit that his records are incomplete, they offer a remarkably expansive look at open-wheel racing in the United States.

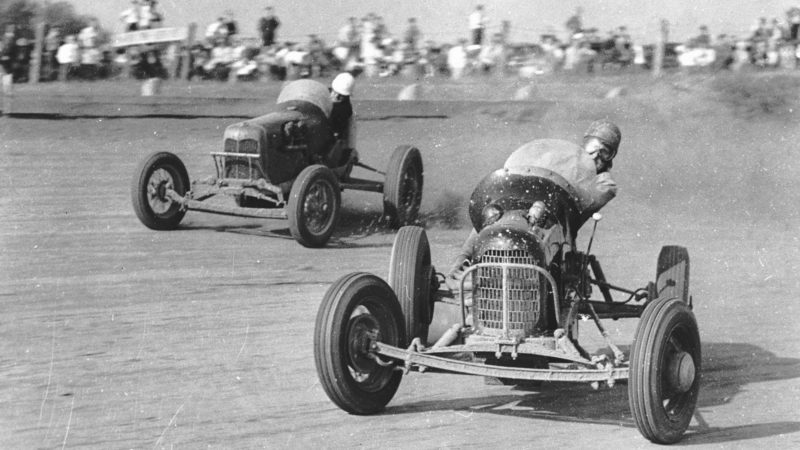

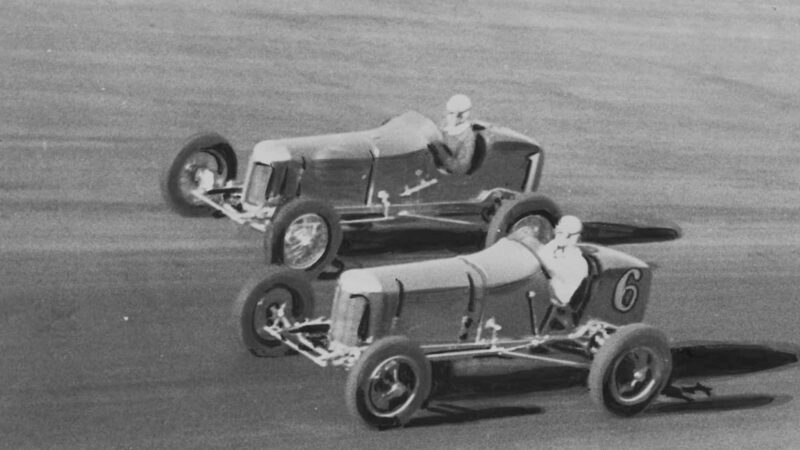

Ferner’s research has shed new light on under-rated names like Ernie Triplett, here in car No1 alongside Bob Carey in San Leandro, California

Bay Area News Group Archive via Getty Images

At the moment, Ferner’s Excel spreadsheets contain entries for 31,348 Indycar and sprint car races in the United States and Canada, with 417,652 lines of data about the events, plus another 9,264 midget races, mainly U.S. and Australian, with 84,793 lines of data. He’s also compiled records for 17,964 other car races and 7,881 motorcycle races from all over the world.

Of course, statistics alone are just numbers. Ferner’s voluminous records also tell compelling stories about the breadth of the American racing scene; in certain regions, in certain eras, there seemed to be a racetrack in every town with more than a couple of stoplights. Chassis histories also trace the serpentine trails cars took on their way from team to team and then from series to series as they were progressively modified to stave off obsolescence.

By looking at the big picture, Ferner has been able to shine the spotlight on some figures who’ve been unfairly overlooked. “Someone like Ernie Triplett is very much under-appreciated,” he says. “People say, ‘He never finished in the top five at Indy. He can’t have been very good.’ So he’s been completely forgotten. But he was really a superstar in the ’30s.”

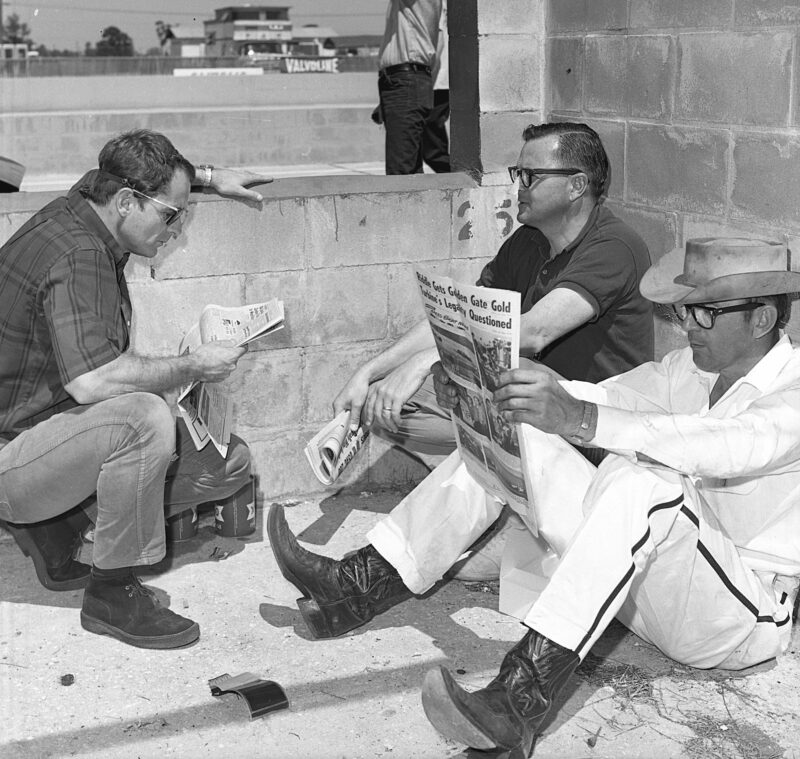

Mechanic and designer Henry ‘Smokey’ Yunick reads National Speed Sport News, which covered the US scene from 1934 to 2011

ISC Images & Archives via Getty Images

One setback in Ferner’s effort to fill in the gaps in his data is his inability to get his hands on National Speed Sport News, which was the weekly bible of oval-track racing in the States for nearly three quarters of a century. But while he searches for more information, he continues to investigate other forms of racing.