Of course, the problem was that tuners – especially those trying to squeeze more horsepower out of the Japanese fours, which were starting to take over the world – were trying to make silk purses out of sow’s ears.

These were genuine streetbikes, a million miles from today’s purpose-built superbikes, which is why the first years of US superbikes were more about sports twins built by BMW, Ducati and Moto Guzzi, than Japanese fours. Then, bit by bit, disaster after disaster, Kawasaki, Suzuki and Honda learned to reign supreme. At least until the 1990s when Ducati came back from the brink of bankruptcy with its eight-valve twin, created, funnily enough, for WSB.

Superbikes quickly became a runaway success in the USA, because fans were bored of watching grids full of Yamaha TZ750s every weekend. Not only were they hugely entertaining to watch – riders wrestling with their machines as they took them way beyond their design limits – they were also what the manufacturers wanted. These became the days of ‘Win on Sunday, sell on Monday’.

Ironically, it is the man now in charge of MotoGP’s tiresome, but arguably necessary, track-limits and tyre-pressure penalties that has the greatest story to tell of those early years of supers racing.

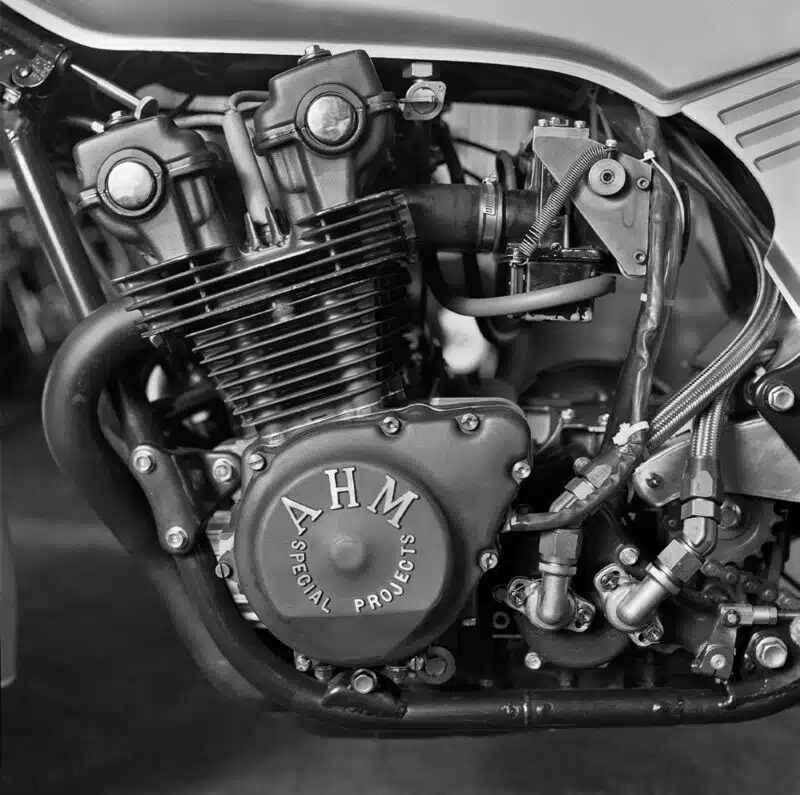

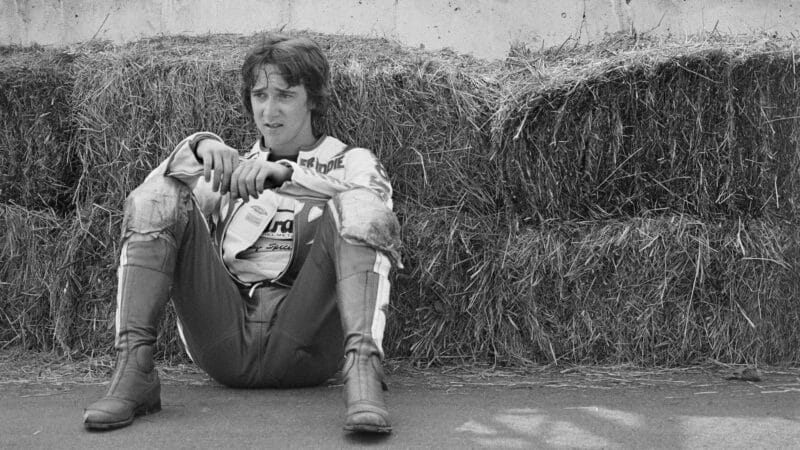

Freddie Spencer, who made his name on TZ750s and TZ250s, had his first supers experiences in 1979, riding a Kawasaki Z1000 and (yes!) a Ducati 750SS. His talent was so startling that within months he was snapped up by American Honda, to ride its 1023cc CB750F superbike.

Spencer doesn’t seem to be looking forward to doing battle at Loudon, where track safety was, erm… unsafe. In 1979 the future three-time world champion mostly raced two-strokes, but had his first superbike races on a Ducati 750SS and a Kawasaki Z1000

John Owens

The CB was an animal, like all Japanese fours of the time.

“That bike just flexed all over the place,” Spencer recalls. “In fact I’d literally bend the handlebars, just from counter-steering the thing to get it to turn. And it was really unstable. Everything was just bad.

“Plus it had so much engine compression that you’d go into a corner, roll off the throttle and the bike would start hopping. And once that started it would hop right off the racetrack.”