Sixty years on from Breedlove becoming the fastest man on earth for the very first time, it’s interesting to see why 400mph seemed such a difficult barrier to break, while 500mph and 600mph were so comparatively easy.

Of course that first run of his was not a land speed record as such, as to comply with the FIA’s then-definition of an eligible vehicle required a car with four wheels and to be driven by at least two of them. His Spirit of America was a jet-powered three wheeler. The only land speed record set above 400mph and recognised as such at the time was the 403mph achieved by Donald Campbell in his wheel-driven, four-wheeled Bluebird-Proteus CN7 at Lake Eyre in Australia, 11 months after Breedlove had done 407mph. So while Campbell was undoubtedly the LSR holder, he was never the fastest man on earth.

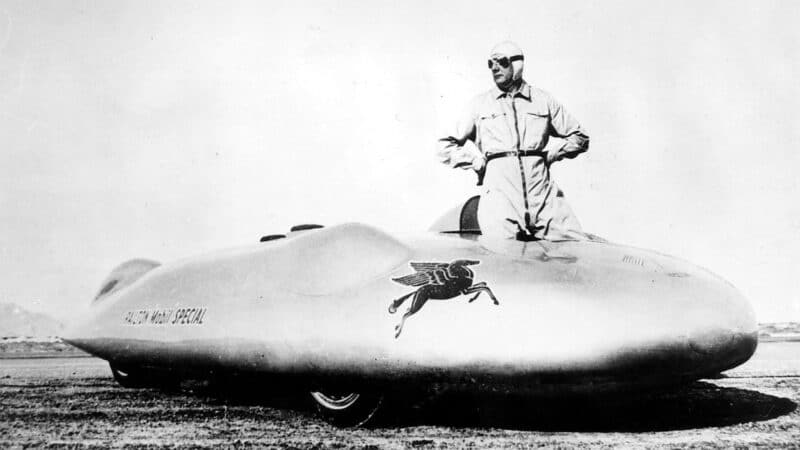

Breedlove with Spirit of America at Bonneville in 1964. His run of 526.28mph would make him the first man on land to top 500mph

The requirement for land speed record vehicles to be wheel-driven was dropped in 1964. The interesting thing is, to this day, while the outright LSR is the same 763mph achieved by Andy Green in Thrust SSC at Black Rock desert on October 15, 1997, the wheel-driven record has risen by just 53mph to 458mph, set by Don Vesco in his ‘Turbinator’ at Bonneville in 2001. Indeed only once has 500mph ever been achieved by a car driven by its own wheels, a speed reached by 76-year old Dave Spangler in ‘Turbinator II’ at Bonneville in 2018. But it was a peak, not an average speed and in one direction only, both of which disqualifies it from official record holding status.

So what makes a wheel-driven 400mph so damn difficult? Let’s look in the other direction: in the 1930s, the LSR advanced steadily thanks to the efforts of three great Britons, Sir Malcolm Campbell, George Eyston and John Cobb. On the first day of the new decade it stood at 231mph, on the last some 367mph. Then, to be fair, a global conflict got in the way so it would be 1947 before Cobb could take his monster Railton Mobil Special out of mothballs and raise the mark to 394mph becoming, I should say, the first person to break 400mph on land, if not set a record above that speed.

Who’d have thought it would take so long for those last few mph would be added? When Cobb set the record in 1947 no one had even flown faster than the speed of sound; by the time Campbell raised his record by just 9mph, 11 men and one woman had already been into and returned from space.

The LSR has come a long way since John Cobb – pictured here in 1947

Getty Images

The reasons for this, however, are not difficult to understand. Huge speeds require not just huge power, but minimal drag too. But the problem encountered by Cobb and co is that even the more beautifully rendered teardrop body shapes presented an enormous frontal area when, as was the case with his car, it had to house two 26.9-litre, supercharged, twelve-cylinder Napier Lion aero engines. Of course Donald Campbell’s solution to that was to use a long, slender gas turbine instead, but that only addressed one of the problems.