F1 snore-fest shows new cars badly needed: Up/Down Japanese GP

The 2025 Japanese GP showed a much more extreme change than next year's technical regulations is needed to make racing at classic F1 tracks interesting

The four-wheeled Tour de France pre-dates its two-wheeled namesake and was once equally pivotal to its sport. Then its history took a different course.

The start of the Le Mans special test on the 1964 Tour de France. Lucien Bianchi’s Ferrari 250 GTO, the eventual victor, is centre

In its heyday, the automotive Tour de France shared many characteristics of its two-wheeled namesake. Both were sponsored and organised by newspapers, with L’Auto somewhat ironically backing the bike race whilst Le Matin breathed life into the car marathon. Both covered large flanks of the country, with a tendency to drift towards the more pointy landscapes and wine-growing regions. Both incorporated a variety of tests – time-trials and sprints for the men in lycra, hillclimbs and race tracks for those in fireproofs. And both were deemed, in their day, to be the foremost test of man and machine in the respective sports. But whereas one continues to be a centrepiece of the sporting calendar, the other has fallen to a position of relative anonymity. Why?

‘In the world of bike racing, the Tour de France is recognised as the world’s greatest event,’ read Motor Sport’s report on the Nice-to-Nice epic in 1954. ‘All other forms of long-distance racing are reckoned to be mere practice runs in preparation for the big event. If the Automotive Club de Nice continue to organise the Tour de France for cars as they have done over the past four years, then it is quite likely that the event will be placed as highly in the rally world as its namesake is in the pedal world.’

For a few glorious decades, this preposition appeared on track to reality. Some of the most evocative names in the sport won the Tour through the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s, the likes of Olivier Gendebien, Lucien Bianchi, Vic Elford and Patrick Depailler. They did so in some of the sport’s most iconic cars, with wins falling to the likes of the Ferrari 250 GTO, Lancia Stratos, Ford Mustang and Renault 5 Turbo, who took on cars as humble as the Citroën 2CV on the open roads of France. Like today’s bike race, the Tour would venture into neighbouring countries to pace some of the most fabled terrain on the continent: Spa, Nürburgring and Monza among the regular fixtures, as well as France’s finest circuits from Le Mans to Reims-Geux. It was a definitive grand tour at a time when freedom of travel was increasingly of the essence.

Straddling race and rally, the 1954 test covered 6,000 kilometre from Nice-to-Nice with nine special tests along the way. Of differing type, they ensured ‘no partiality to any particular type of car.’ From Nice to the base of the Pyrenees, the route then headed north and inland to Le Mans for a timed test at la Sarthe, before heading to Nancy where drivers took on a half-kilometre acceleration test with points deducted for the slowest. The north coast followed before the Tour headed through iconic two-wheel country – Roubaix, Paris and through Champagne district for another speed test, this time over the 8.3km Grand Prix circuit of Reims-Gueux. Then another hillclimb, the Montet-Brabois at Nancy, before making tracks back towards Nice via the Maritime Alps and a climb up the infamous La Turbie mountain road to the summit of the Grande Corniche. Finally a 47-lap of a Nice circuit concluded a true tour of France.

Two Ferrari 250 GTOs in action during a test at Reims-Gueux during the 1964 Tour de France

As is the case in the bike race, few gains were to be made on the connecting stages and instead survival was key. Mechanical dramas, disqualifications and loss of time dropped many out of the reckoning, but the race was always going to be decided on the mountains and timed tests, something Chris Froome knows well, and it wasn’t just the machines who were tested to their limits either. Nights in a hotel at the stage ends may have seemed a luxurious way to tour, but forget it – time to rest was minimal and after ten arduous days on the road, physical resources were drained. Of the 122 starters in 1963, only 31 survived the journey.

A test for cars, a test for drivers, but the Tour’s earliest days were a test of survival for the competition itself. The very first race in 1899 was something of a groundbreaker at a time when road racing in Europe was very much still a hatchling. Only nineteen cars took the start, nine reached the finish and it was to be the last tour for another 13 years. The humble Panhard of Rene de Knyff was the victor of that first race, covering 1,350 competitive miles. He was fastest on every stage and enjoyed a stroll of a tour compared to Camille Jenatzy who regularly finished 20 to 40 hours behind the leader. Remarkably, by driving through the night he reached the finish just four hours behind the leader with an average speed of just 8.1 mph.

Propped up by the media barons who backed the race, the Tour had a shaky start and it wasn’t until 1912 that the race was organised again. Fatalities on the Paris to Madrid in 1903 brought in restrictions and in some cases total bans and obtaining the free use of the public road for racing cars was an increasingly challenge. A class for light aeroplanes was added in 1931, quickly dropped when the Tour returned another 20 years later along with the motorcycle class, but the entry for cars was left wide open. Citroëns took on Ferraris and into the ’60s the Tour was an event of astonishing prestige, lasting ten days with several hundred cars and rivalling today’s two-wheel marathon for grandeur with huge public interest.

The Matra Sports factory fielded an entry in 1970 with its Le Mans-derived prototypes, piloted to victory by F1 aces Jean-Pierre Beltoise and Patrick Depailler, whose co-driver was a certain Jean Todt. It was the simplicity and purity of the competition that drew the big names. Scrutineering was conducted in a small Esso petrol station on one of Nice’s busiest crossroads and the open road hosted the connecting stages, but this was no laid back grand tour. In 1970 the test at Montjuich Park in Barcelona was such a scorcher that Vic Elford and Jean-Claude Andruet in their Ferrari Daytona had to be revived with oxygen afterwards and shortly after torrential rain lashed down leaving the roofless Matra crews sat in inches of water.

These years were the Tour’s moment in the sun, when the rules were free and the greats of the race and rally worlds could duel it out on an even footing, with a handicap system and varying tests ensuring the competition was wide open. Unfortunately, it wasn’t to last. An oil crisis, the stranglehold of red-tape and TV demands to focus on a single circuit rather than following a continent-straddling tour forced the competition into steep decline and, incorporated into the European Rally Championship in the ’70s, it survived only until 1986 when the Group B cars were banned.

The Tour de France visits the Circuit Rouen les Essarts in 1964

Competition was revived in 1992 as Tour Auto, open to pre-74 machinery and taking in race circuits and hillclimbs across the country on a four day tour. Several hundred cars enter and although the glory days of the Tour are long over, the name ‘Tour de France’ remains equally evocative. The Ferrari 250 GT ‘Tour de France’ of the ’50s is, quite simply, the most valuable car in the world – one sold for just shy of £23 million in 2014 – and a year later Ferrari heralded that great history with a limited-edition V12 mega-machine under the same name.

For many commentators it failed to live up to the name of its predecessor, perhaps an ironic reflection of the great race itself, although the Tour is so much more than that. It embodies the pure enjoyment of driving, which was after all the rationale for so many of the great cars that take part. It’s therefore a healthy antidote to the often politicised world of top-flight motor sport today, and that’s something certainly worth holding on to.

The 2025 Japanese GP showed a much more extreme change than next year's technical regulations is needed to make racing at classic F1 tracks interesting

Max Verstappen looks set to be pitched into a hectic, high-stakes battle for F1 victories in 2025, between at least four teams. How will fans react if he resorts to his trademark strongman tactics?

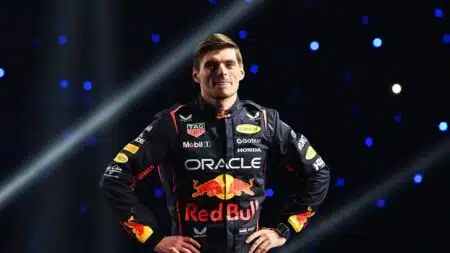

Red Bull has a new team-mate for Max Verstappen in 2025 – punchy F1 firebrand Liam Lawson could finally be the raw racer it needs in the second seat

The 2024 F1 season was one of the wildest every seen, for on-track action and behind-the-scenes intrigue – James Elson predicts how 2025 could go even further