Despite the ever-present risk of a catastrophic crash, Attwood found himself leading the 1969 race, thanks to the pace of the car until, in the 21st hour, a gearbox failure ended his race. He says that he wasn’t disappointed for a second.

“I was quite happy when it broke. We were only three hours away from the win but I wasn’t concerned about that. I was concerned about me. I couldn’t have cared less about the race.”

So, the following year saw Attwood in the 917K, opting against the power upgrade used by other Porsche entries, in the hope of avoiding a repeat gearbox failure.

“The car was a lot slower than anyone else’s 917 and the Ferrari,” he says. “Mulsanne corner and Arnage – two really short corners – we must have been losing 2-3 sec out of just those each, and then we were losing time all round the rest of the lap as well.”

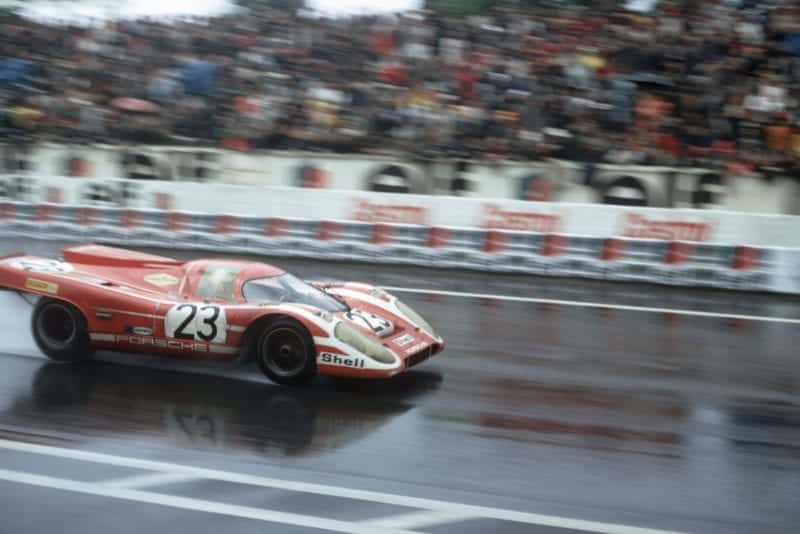

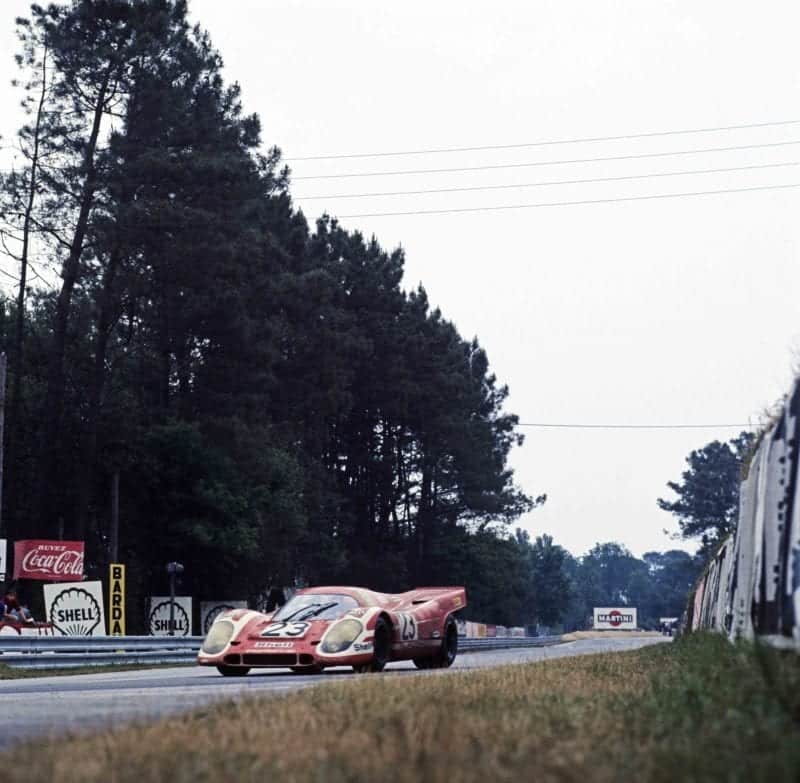

Expectations dampened, Attwood watched Herrmann start the race in their No23 car. “Just before the race the whole place goes completely quiet. That doesn’t happen any more because of the rolling start, but to have all those cars lined up – before the flag drops, the silence was just deafening. It was an incredible atmosphere.”

51 cars begin the race… seven would be classified at the end

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

It was the first year that drivers did not start in the traditional manner of running to their cars, and Denis Jenkinson was unimpressed, describing the dropping of the flag as the moment that the race fell over and died.

Attwood recalls the first laps somewhat differently. “The start of the race was like a grand prix,” he says. It was just ridiculous – everybody else was quite stupid.

“They were all trying to get round on the first lap in the lead – and the second and the third laps. All these guys realised they could win it with the cars they got but they had to last the race as well.

“The pace was just stupid and the race came to us, as Le Mans does. It either comes to you or it doesn’t.”

After 30 minutes the rain began, and car No23 began moving up the field.

“Four Ferraris went off in one accident,” says Attwood. “One of the Porsche factory drivers [Siffert] missed a gear and over-revved it. The other driver [Porsche’s Mike Hailwood] didn’t come in when it was raining. He had dry tyres on and crashed.”

By the early hours of the morning, Attwood’s Porsche was leading. “We had done nothing for that to happen,” he says. Everybody had made way for us to be the leader.

“The others might think they had bad luck, but you make your luck and a lot of them made mistakes – silly really.”