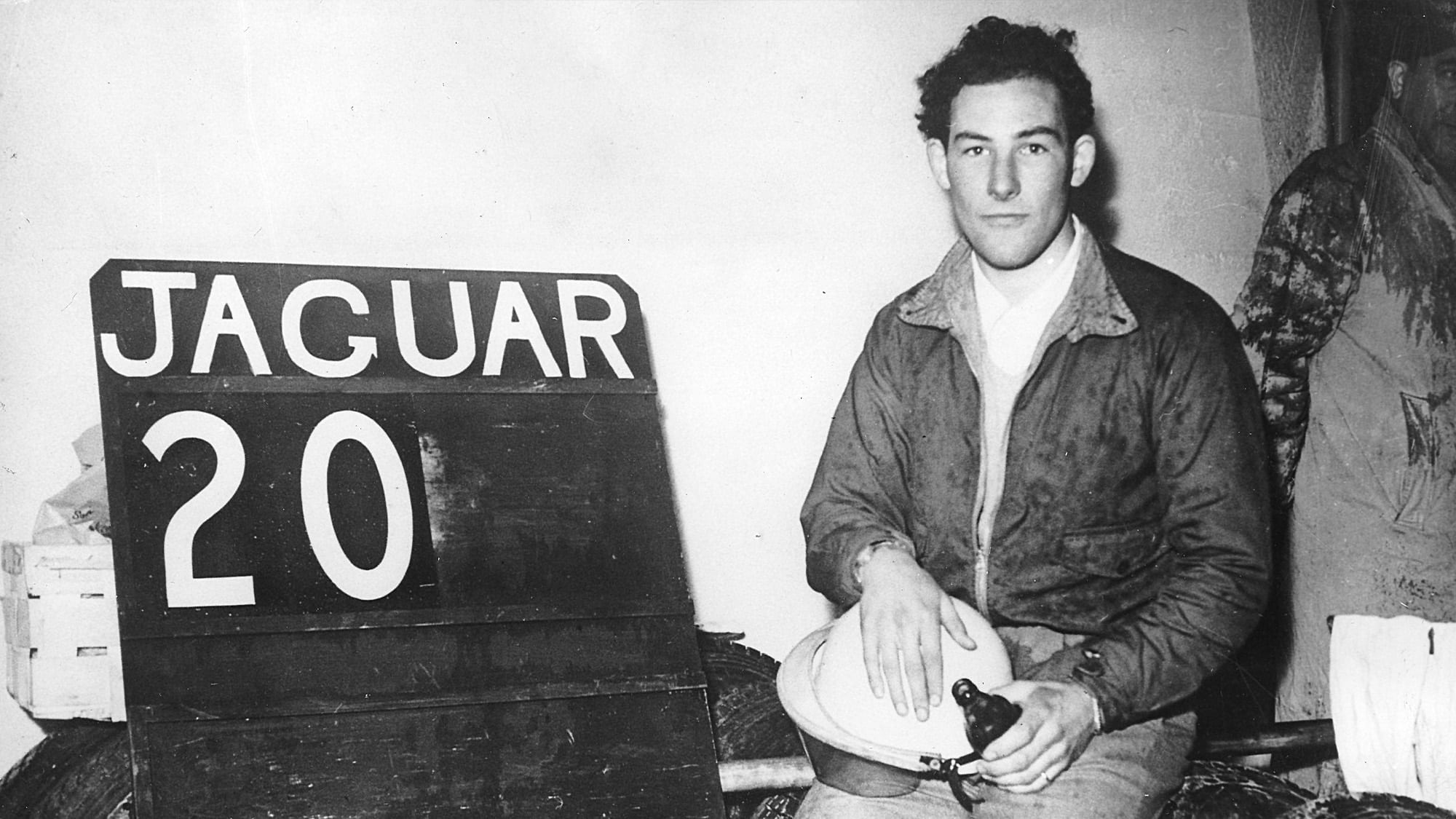

At his first Le Mans in 1951 Moss almost immediately made his mark and was in the lead after three laps. He broke the lap record repeatedly, eventually setting a new mark a full six seconds below Louis Rosier’s from a year earlier. By the end of the second hour he’d lapped the whole field; by hour four he was two laps ahead. But having broken his opposition, the race broke his car, as it so often would. Just before midnight, having led for seven hours, a conrod bust due to a lack of oil pressure. Still, his job was done: Jaguar went on to win Le Mans for the first time, thanks to the sister XK120 driven by Peters Walker and Whitehead.

Perhaps Moss’s ambition and impatience was unsuited to 24-hour endurance racing. The following year his drive to push for more performance arguably cost Jaguar the race before it had even arrived at La Sarthe. Following the Mille Miglia in which he had been impressed by the form of the new Mercedes-Benz 300SL, Moss impetuously sent a cable to Jaguar chief Sir Williams Lyons: ‘MUST HAVE MORE SPEED AT LE MANS’. In haste, Jaguar’s engineers modified the new C-type, fitting longer noses and tails with smaller air intakes for the radiators. All three promptly retired with over-heating problems as a pair of 300SLs swept to a German one-two – just seven years after the war had ended.

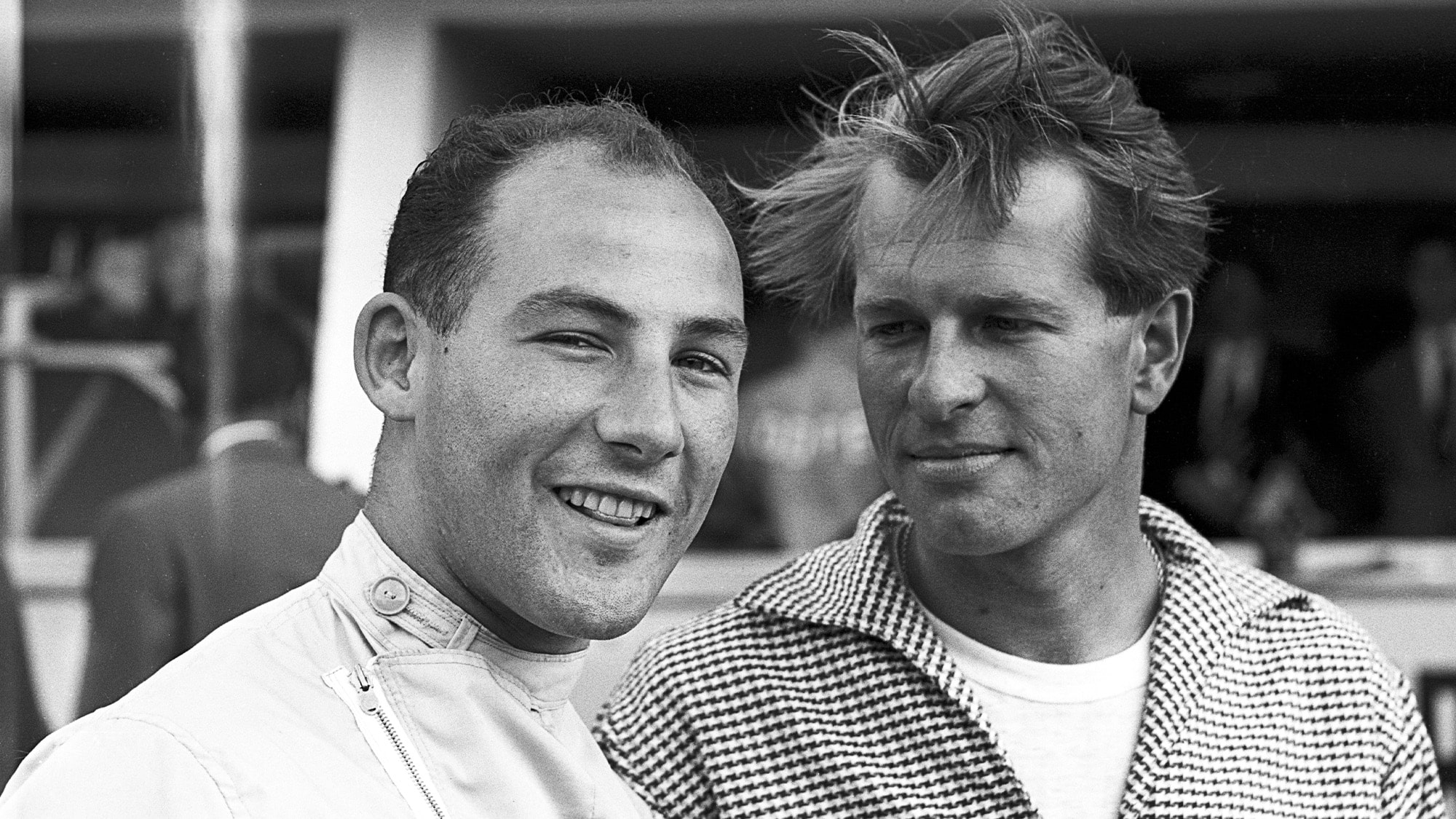

Moss (right) and Walker on the pitwall in 1953 with(left) Jaguar team manager Lofty England

Ronald Startup/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

But Moss’s finest attributes were back on show at Le Mans in 1953 as the C-types returned, now fitted with disc brakes that helped give them a clear edge. Having led – naturally – Moss and Peter Walker were delayed by a misfire. Their recovery charge, one of the finest ever seen at Le Mans, carried them to fourth by morning and to a remarkable runner-up spot at the flag, behind Tony Rolt and Duncan Hamilton’s winning C.

“It was probably the nicest Jaguar ever built,” said Moss. “Wonderful because we developed the car and developed the disc brakes. It really did need them. The [drum] brakes were alright-ish on the XK120, but on the C-type they weren’t because the car was a lot faster. So from that development point of view it was my favourite Jaguar.”

Moss inevitably led again in 1954 as the svelte new D-type took its bow, only for unreliability to once again bite. But by 1955 Stirling’s career had taken an upward turn – even if it was a ‘foreign’ one. At Mercedes beside ‘El Maestro’ Fangio in a dual attack on grands prix and the World Sportscar Championship Moss had his chance. In F1, he reverentially and without complaint assumed the role of apprentice to the man he respected above all others – but in a sports car, Moss had Fangio’s number.

“Fangio, to my mind, was the best F1 driver in the world,” Moss would always say. “But I could beat him in sports cars, which is something I don’t understand. He didn’t like enclosed wheels, but in F1 he was very fast. He was braver than me too, actually. At a place like Spa he was exceptionally quick. It was a very daunting circuit.”