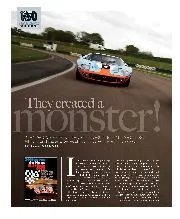

A large rear wing upset some purists, although some cars did run one at Le Mans in ‘71. It also had air jacks, which were unknown in its heyday. A 4-speed CanAm gearbox was used, and there was a choice of 4.5 and 4.9-litre power units.

By now dubbed 917K-81, the bright yellow car was given a shakedown on the Nürburgring short circuit just before Le Mans.

“It appeared to be a very easy car to drive, actually,” said Wollek. “I’d been driving 935s with up to 740bhp, so I wasn’t impressed by the power. But it was well-balanced, and didn’t seem to be what people had told me about 10 years before.

“But when we got to Le Mans the car was desperately slow, or at least the lap times were not there. Eventually we realised the car was slow in a straight line, perhaps because they’d added a big wing on the back and some downforce on the front, which actually made the car easier to drive. But it was ridiculous compared to the speeds the 917s used to do 10 years before.”

A change of ratios made a big improvement, but Wollek had more on his mind than technicalities.

“Funnily enough, it was the very first and last time in my life that when I left my house, I had a very bad feeling. I just did not feel right – I felt that something was wrong, something was going to happen to me. I was very, very uncomfortable. I just did not know why, and that feeling started when I left my house, and it just followed me all the time.

“When the race started we were still slow, and were nowhere, miles behind the leaders. Which upset me, because I honestly thought at one stage we had a good chance to finish well up.”

The 917 still looked the part at Le Mans in 1981, but was off the pace of the modern machines

Klemantaski Collection/Getty Images

The first hours of the race were scary, and saw a series of horrific crashes on the Mulsanne Straight. In one a marshal was killed by debris from Thierry Boutsen’s WM, while in another Wollek’s contemporary Jean-Louis Lafosse lost his life. Although he’d got up to ninth, Bob was deeply unhappy.

“This was too much. I could not take it anymore. I spoke to a friend I met in the pits and said to him, ‘I don’t like this, I hate this race. The only thing I’d like to do is **** off and go home.’

“He said, ‘Why?’ And I said, ‘I just get the feeling that I’m going to get killed here’. He said, ‘You know what, Wollek? **** off and go home.’ ‘You think I can do that?’ ‘Of course, if you don’t feel OK, **** off.’ So I ****ed off…

“My intention was just to go home, get out of this. I didn’t want to drive that car any more.”

“I went to the pits and I spoke the Kremers and said, ‘Look, I’m unhappy, I don’t feel well, something’s going to happen to me. I don’t want to go on.’ And I left. Which never ever happened to me before or since. I went back to the hotel, packed and drove home.

“At that stage I thought it was the thing to do, and looking back, I did it right. Kremer couldn’t understand, and they thought that I was going to retire from racing. But my intention was just to go home, get out of this. I didn’t want to drive that car any more.”

Few people noticed that he had even left, because the car was withdrawn in the eighth hour, after Lapeyre had damaged it.

“Two weeks or so later there was a German championship race with the 935,” Wollek recalled. “The Kremers spoke to me on the phone and said, ‘What do you want to do?’ I said, ‘No problem.’ ‘What about Le Mans?’ I said, ‘I told you before, and that’s it. Forget about it.’”