His and team-mate Bailey’s ’89 La Sarthe jaunt was over before it had really began – “the shortest Le Mans ever” – after brake failure meant the latter spectacularly rear-ended another competitor in race-ending fashion on lap five.

Things had got better in the ’89 season with a pair of podiums at Donington and Spa, with more following in 1990 but even these relatively successful weekends weren’t without their hiccups.

“Back then things were a lot more raw and agricultural,” he remembers. “So there was a lot more actual testing on track to find out what’s going on as opposed to using data.”

Never did this become more apparent than at Dijon in 1990.

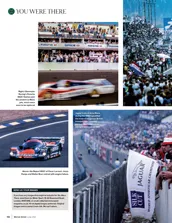

A turbo monster with no power steering, Blundell says the R90CK was extremely physical

RM SOtheyby’s

“The car managed to get an airlock inside the cockpit and punch the windscreen through from inside out,” says Blundell.

“I remember the screen popping out and going up probably 50 feet in the air, into the crowd! It wasn’t ideal.”

Come Le Mans ‘90, reliability issues with the R90CK still hadn’t been overcome, further exacerbated by a car more geared towards one-lap pace rather than endurance events.

Podiums showed promise – when Nissan wasn’t breaking down

DPPI

“We were going to Le Mans on the pretence of having a qualifying car as such, which was basically because we had a qualifying engine,” he says.

“So we knew that we were taking something there that had a huge amount of increase in performance compared to what we had previously, but no understanding of what it was going to be like until we got there, because we hadn’t tried or tested it [in this spec].”

Blundell had flipped a coin with Bailey over who would do the qualifying run and who would take the race start – that was if it could even manage a lap.