First, however, he was a businessman in Japan, connecting rapidly growing companies with Western expertise and rubbing shoulders with Japanese executives. Which is how he found himself involved in the Fuji Speedway project.

The story is told below in an extract from a new book about Nichols and his Shadow team, which includes extensive interviews with the mysterious ‘Shadowman’ before his death in 2017.

You can read more about the book in the latest issue of Motor Sport Magazine. The book is available in the Motor Sport Shop.

The tale of the Fuji Speedway begins in the early 1960s when Nichols joined forces with the Sports Car Club of Japan and wealthy industrial firm Marubeni-Ida to build an oval circuit on the foothills of Fuji. The investors wanted the very best. And they got it.

Extract from Shadow: The magnificent machines of a man of mystery by Pete Lyons

The future Speedway’s site was some 60 miles southwest along the coast from Tokyo on the eastern skirts of iconic Mount Fuji. “We formed a company to design the Fuji Speedway,” said Don. “We had the contract with Marubeni- Ida, which eventually did the financing and construction. I set up the office, and got all the publicity going.

“I came over here [the US] and hired Charlie Moneypenny.”

Charlie Who?

“You’re gonna build a Superspeedway here? Ha-ha-ha…”

Don explained that Moneypenny was a civil engineer who had designed the Daytona Speedway for Bill France of NASCAR, as well as Talladega Superspeedway and other big banked ovals in stock car country. Not only did his Japanese friends want to engage The World’s Foremost Circuit Designer, they aimed to partner with The Biggest Players.

Nichols’s own company took on both tasks.

The partners’ high-profile approach called for the World’s Foremost Speedway Designer to visit the building site. “So we brought Charlie Moneypenny over and put him in the Okura hotel in downtown Tokyo, with an office where he could design the Fuji Speedway.

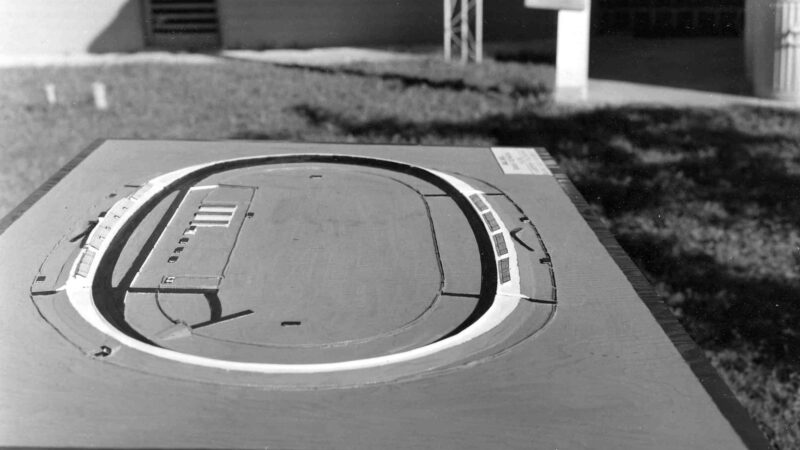

Fuji Speedway as first imagined — by a NASCAR track designer before he had seen the property. When Charlie Moneypenny and Don Nichols got there, both immediately realised it was time to go back to the drawing board.

Don Nichols collection

“At that stage I hadn’t really been to the site and looked at the land. The Japanese said it was an ideal location that they had bought, just above a famous resort, the biggest seaside resort in Japan.

“Charlie showed up, he already had a plan laid out,” Don continued. Indeed, apparently the Daytona man brought along an actual scale model of his idea for Fuji. It showed a fully rounded oval, a sort of watermelon shape with two modestly banked, gently arcing straightaways — like Daytona’s front stretch — connecting a pair of steeper, longer curves.

“Naturally, American speedways are on level ground. He and I went down, and the land was like this.” Don’s long arms indicated a pronounced departure from level. Even on the outer flanks of the majestic volcano the slope is significant.

“He looked at that, and he looked at me and he started laughing. “You’re gonna build a Superspeedway here? Ha-ha-ha…”

Clearly much rethinking and recalculating had to be done

“Charlie said, ‘Can you get a consultant to help?’ I said, ‘Yeah, I know a guy that’s perfect for a consultant.’ Stirling Moss had just had his accident [at Goodwood in 1962, the end of his great driving career]. I hired Stirling to come over. He was like a god to the Japanese.”

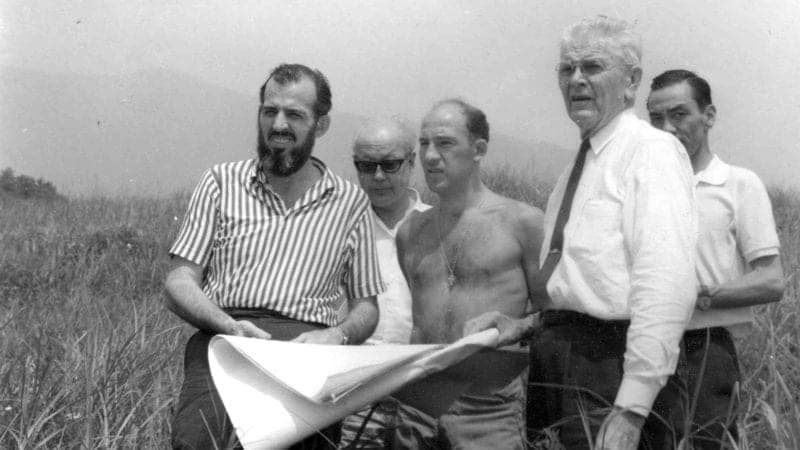

Our interview entered a mirthful stage. “You hired Stirling Moss!” “Yeah. I’ve got pictures if I can find them [he did find them], Stirling with Charlie out in weeds this high…

OK, fellas, here’s what we’re gonna have to do.

Don Nichols collection

“Stirling was in medium health after his accident, but rambunctious. He spent most of his time measuring his temperature from one side of his body to the other. He said, ‘You know, I’ve got this problem. My temperature on my left side, where I had the accident, is really low, and my temperature on this side is too warm.’ But he said, ‘It doesn’t hurt. When I have contact with the opposite sex it doesn’t bother me.’ I said, ‘I think you’d better activate that circulation!’ “He did. He was with us during the day, trampling around in the tall grass, giving his opinions about how a racetrack should be done, and then hurrying back to Tokyo for the night life.”