With his IndyCar career coming to a close, Chilton eventually became McMurtry’s test and development driver along with hillclimb ace Alex Summers. He describes the incredible sensation of driving the car – with fan system engaged – in full anger for the first time.

“I really was blown away,” he says, agreeing with the poor pun offered to him by Motor Sport. “The thing just shocked me straight away, once the fan, power and torque was all on full, is that it was definitely more advanced in some ways than an F1 car.

“Its slow-speed grip and acceleration is just out of this world. There’s nothing that comes close to it – that’s why we started testing at Silverstone because it’s so quick, we needed a big track that we could start pushing the limits on.

“The most backwards thing is that because it generates two tonnes of downforce at zero mph and stays there at whatever speed you’re doing, it doesn’t brake like a normal single-seater. There’s still a bit of technique left for me to get better at that, it’s all a bit odd. There’s still loads of time in it, we haven’t really exploited it fully yet.

“It’s a young team, some of them are ex-F1 engineers, it’s about the way they think. This is banned F1 technology, no-one’s had a fan car competing for 40 years. They’ve put it in the 21st century, and its performance is outrageous.”

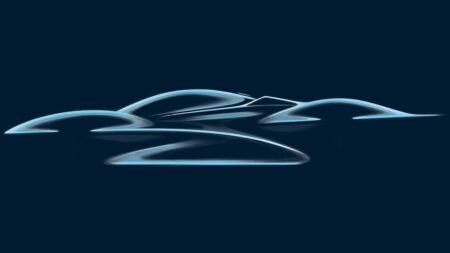

Stubby shape designed for F1 performance

Turton laughs when asked by Motor Sport about the Batmobile-like profile, saying the aerodynamic architecture has simply been borne of necessity, as he explained the unique test and design journey that the Spéirling has been on.

“If you want to circulate a grand prix track in a high-performance electric car as fast as possible, you need to build out from the driver,” he says.

Not your average competition car profile

Jamie Bufton Photography

“You put the driver in a carbon-fibre monocoque with a closed roof that keeps them safe and gives you the aerodynamic efficiency.

“You then fit the battery around them in a low-drag position that minimises the wheelbase, so that’s why the batteries are in the sidepods of the car and underneath the driver’s legs in a ‘u’-shape – that’s to get it in the dead zone between the wheels so there’s no penalty either on drag or the length of the car.

“You place the tyres in a position where the track width is very narrow to reduce frontal area, saving on energy requirements and therefore battery weight.

“Therefore the wheelarches have this LMP-esque bubble architecture, while everything else is about minimum surface area.

“We have gained a rear-wing in the development phase, which was suggested by Max, but it actually only adds about 10% overall downforce. It’s mainly a stability and tuning tool, the rest comes from the fan system, which is the secret weapon.”

Two tonnes of downforce from onboard fan system

The fan produces 2000kg of downforce and 3g of grip through the corners, meaning that at up to 150mph the Spéirling can match the acceleration and cornering speed of an F1 car – quite staggering.

The car has been pounding round Silverstone, Donington and Castle Combe but the McMurtry team has very much been feeling its way through the process – understandable for such an idiosyncratic vehicle.

Small car’s design is built out from the driver, with minimal drag one of the main aims

Jamie Bufton Photography

“With a car designed to no rules you get a lot more freedom of how you test and what you want to test,” Turton explains. “You’re not taking a previous car and tuning it, you’re literally creating the future as you go so there’s probably more challenges, less prior cars to draw experience from.

“You have to go back to first principles: “What we try to achieve with this component? What are the loads? What are the temperatures? What are the materials and techniques you need to achieve it? Every single part of this car is bespoke because it’s only way to achieve our aims.

“We did high-speed testing at Silverstone with the premium asphalt, and got data from the twisty sections at Landau with a more bumpy surface.

Car can produce 3g of grip, when not doing burnouts for the crowd

Jamie Bufton Photography

“We did use a simulation to get the car in the right ballpark for the set-up, but at Goodwood nothing can prepare you for what the drivers have to go through to deliver that lap time. You can’t replicate the fear factor in a simulation!”

Turton and his team have shown gratitude to that final crucial component, the driver.