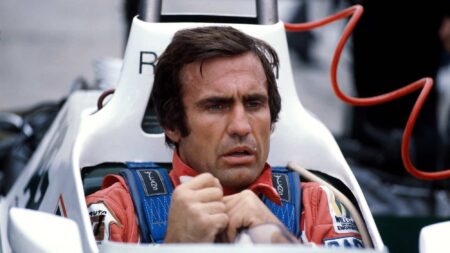

I well remember arriving at Silverstone on Saturday (yes, Saturday; there is nothing new under the sun) July 14, 1979, to watch that year’s British Grand Prix. I was 16, and, although I was disappointed that my hero, Carlos Reutemann, had qualified his ageing, still beautiful, but no longer competitive Lotus 79 only eighth, I was excited to the point of near stupefaction to see Jones’s Williams FW07. Why so? Well, let’s put it this way. The qualifying time that had earned Reutemann his P8 was 1min 13.87sec — 0.76sec slower than that of Jones’s Williams team-mate Clay Regazzoni. But Jones was in another world, a chasmic 1.23sec better than Regazzoni and a scary 1.99sec faster than Reutemann.

Jones did not finish that race – his water pump failed at half distance, at which point he had been cruising to an easy win — so Regazzoni scored Williams’ maiden F1 grand prix victory. It was a popular result – because Clay was a lovable rogue – but in truth Alan deserved it not only because he had helped Frank Williams and Patrick Head launch and nurture Williams Grand Prix Engineering, as it was then called, but also because he was the better and faster driver.

He was faster and better than not only Regazzoni, but also than anyone else at that time. You doubt me? OK, let’s study his principal rivals through the specific prism of Jones’s purple patch, in other words the 1979, 1980 and 1981 seasons. In terms of a tiny number of drivers’ stunning and perhaps god-given ability to climb into an F1 car and straight away turn a superfast lap in it, irresistibly fluent yet effortlessly nonchalant, Ronnie Peterson was the 1970s exemplar; but he had died in hospital of wounds sustained at Monza in 1978. Gilles Villeneuve was still alive and well, but in 1980 and 1981 his Ferraris were lively and unwell: ‘slow’ would be another word, although at Monaco and Jarama in 1981 he bludgeoned his powerful but unwieldy Ferrari 126CK to two improbable victories nonetheless.

Legends like Andretti, Hunt and Fittipaldi were fading forces by 1979

James Hunt was well past his briefly magnificent 1976-1977 best by 1979, and he retired after that year’s Monaco Grand Prix, having failed to finish that race and the three that had preceded it. Niki Lauda lasted just six grands prix longer than Hunt did before he, too, threw in the towel before the end of the season. Mario Andretti was 39 by the time 1979 was just two grands prix old; perhaps he, too, was also not as sharp as he had once been, his acuity blunted by having to battle with his once unbeatable Lotuses that had been outclassed by more efficacious ground-effect designs.

Double F1 world champion Emerson Fittipaldi was still only 32 in 1979, but he had last won a grand prix four years before that and since then he had been languishing in uncompetitive Copersucar-Fittipaldis; he was never a force in F1 after he had left McLaren at the end of 1975. Although Jody Scheckter became F1 world champion in 1979, driving fast and reliably to achieve his long-yearned-for objective, by his own admission he had set out that year to accumulate points by occasionally and judiciously settling for podium placings rather than gunning for wins at all costs, as he might have done a few years before, when one of his nicknames had been Fletcher, after the baby seagull in Richard Bach’s 1970 novella Jonathan Livingston Seagull, who tried to fly when he was too young to do so and as a result kept crashing into cliff faces. In 1980, his hunger sated by his 1979 world championship success, he was distracted and ineffective, and he retired at the end of that year.