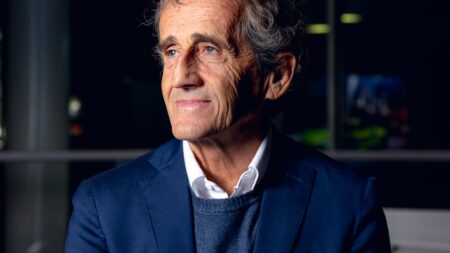

But do such people actual care how we remember them? That thought was forefront recently when I met Alain Prost for a rare interview. You can read the results in the March issue of Motor Sport, which has gone on sale this week.

This is one of the greatest racing drivers who for more than a decade set the benchmark in F1. Yet through the prism of a certain rivalry and too-binary perceptions of how he supposedly operated has found his career ‘tarnished’ (that word again) by a quick-to-judge – and quick-to-post – critical world. The label on Prost’s box claims that he was ‘political’.

I wondered whether it bothers him. After all, no amount of sniping can ever take away his own memories of those years. He knows how good he was and why he was able to achieve what he did, and that’s what counts the most. Isn’t it? But I also knew as I headed down to the McLaren Technology Centre to meet him that it was a bit of an issue. He has touched upon it before. Still, I wasn’t expecting him to be quite so open about how much it troubles him. It really does hurt and he appears a little bewildered by how he is perceived.

Prost showed his mettle at Renault

Grand Prix Photo

“I do ask myself sometimes how I am going to be remembered,” he admitted in his quiet, considered manner. “What you said about the political things… It sounds like a joke but I’m completely underrated! I know that. I can see. I don’t know why, but it’s my brand in a way.”

The reality is most of us care about what other people think of us – even those who claim they don’t. OK, perhaps Kimi Räikkönen, the most insouciant of them all, really couldn’t give a hoot – but it’s human nature to want to be liked. We all have egos, for the best of us to be the image that is portrayed to the wider world, be it in our social media posts or how people feel about us when we actually meet in the flesh. Of course Prost cares. I bet Andy Murray does too. Jackie Stewart certainly does.

In Prost’s case, the failure of his years as an F1 team owner, for a time, threatened to consume our view of him. He certainly took a battering in his native France, although as he alluded to in our interview his relationship with his home nation was always complicated.

Prost’s supposed role in rivalry with Senna can overshadow his achievements

Pascal Pavani/AFP via Getty Images

But has that lost Midas touch once he stepped away from the cockpit really affected how we recall Alain Prost in the long-term? No. Today, we remember the racing driver first. The young man who fully belonged at the pinnacle the moment he arrived in a mediocre McLaren in 1980; who quickly established himself as the most complete F1 driver of his era in the yellow and black of Renault; who ascended finally to the status of world champion back in the Day-Glo and white of McLaren; who then found himself spiralling into the most toxic – yet celebrated – rivalry of them all. That’s Alain Prost. Not the harangued, aging before our eyes, haunted figure that stood biting his nails on pitwalls as his blue cars once again fell way short of his own high standards.

Legacy? It’s a pompous word. But how we are remembered does count, it does matter. Fortunately, it’s also human nature that for the majority who have left a positive mark, in whatever field of work or play, we tend to focus on the best of them. Yet there are unfortunate – and unfair – exceptions.

Is Alain Prost one of them? I really hope not.