While it’s right that incidents and reactions to them should come under scrutiny – could a VSC not have been a better solution, for example? Was there an appropriate gap in the traffic where a VSC would have made it safe for a marshal to retrieve the mirror? – it’s worth remembering just how far we’ve come in the constant quest for improved safety standards. One only has to think back to the barbaric deaths of Tom Pryce and the marshal Frederik Jansen van Vuuren in the 1977 South African Grand Prix to understand just how an apparently innocuous situation can escalate horrifically quickly.

An incident in the 1980 USA West Grand Prix at Long Beach carried the potential for something serious but thankfully ended up being almost comedic – although, like Sunday’s mirror incident, it did seriously spoil several drivers’ races.

It was in the early laps of the race when Bruno Giacomelli spun and stalled his fuel-heavy Alfa Romeo under braking for the hairpin preceding Shoreline Drive. The braking area came just after a blind exit kink and as Carlos Reutemann was confronted by the spun car taking up most of the width of the track, he braked his Williams heavily to a stop, as he couldn’t move to where the gap was because the Brabham of Riccardo Patrese was partly alongside. Patrese nipped through the gap but Giacomelli – who’d got the engine started – selected reverse and moved to where Reutemann was trying to get by.

Mark Hughes

Combined, the two cars were now blocking the track and as others came around the kink, there followed a classic concertina-style series of collisions. When it had all been sorted out and Giacomelli had got on his way, the Lotus of Elio de Angelis was left heavily damaged on the left of the track. It was off the racing line, but immobile. Elio had hurt his ankle and limped off to the side of the track. The marshals set about getting his car moved and for the next several laps, one of them was stationed in the middle of the track at the fast kink, indicating that the drivers should stay right as they exited, not left, where the Lotus was now being loaded onto a pick-up truck! It was of course potentially lethal, and there were two wrecked cars – Jean-Pierre Jarier had ripped a wheel off his Tyrrell – but a single ankle sprain was a good outcome.

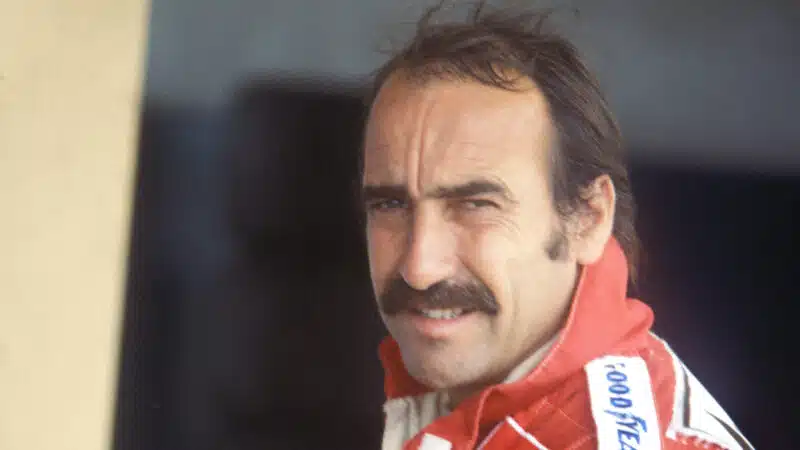

Despite missing the mid-race pile-up, the 1980 Long Beach GP would be Clay Regazzoni’s last

Grand Prix Photo

But that butterfly wing effect did have a tragic consequence later that day. If Clay Regazzoni had got caught in the concertina accident rather than scraping by in his Ensign, he’d have taken a harmless non-finish and a lift back to the pits. Instead, he was still in the race many laps later when his brake pedal snapped at the end of Shoreline Drive, putting him into the tyre barrier at horrific speed, leaving him paralysed from the waist down for the rest of his life.

We’ve come a long, long way. But there is always room for improvement. What happened on Sunday shouldn’t be used as a stick to beat anyone with, but rather a series of lessons which can be used for further progress.