As Gordon says, this was a different South American to the Brazilians who began to cross the Atlantic and plot their path to F1 in the same era. Reutemann was a cattle rancher’s son from Santa Fe, who began racing in 1965 and was chosen five years later by the Automovil Club Argentino for a sponsored season in Europe driving a Brabham BT30 in Formula 2. Unlike Fittipaldi, it didn’t all click immediately but he finished runner-up to Ronnie Peterson in 1971 and was signed the year after by Bernie Ecclestone, who had completed his purchase of Brabham. Remarkably, he qualified the ‘lobster claw’ BT34 on pole position for his first grand prix, at home in Argentina.

More nuggets would follow in the BT42, but it was in the BT44 in 1974 that he really started to get motoring. He led the first two grands prix that year and won the third, in South Africa. Then unfathomably his form dropped away – only to return in spades at the Austrian GP. He won the season-ending US Grand Prix too: three wins, yet only sixth in the world championship. That was Reutemann.

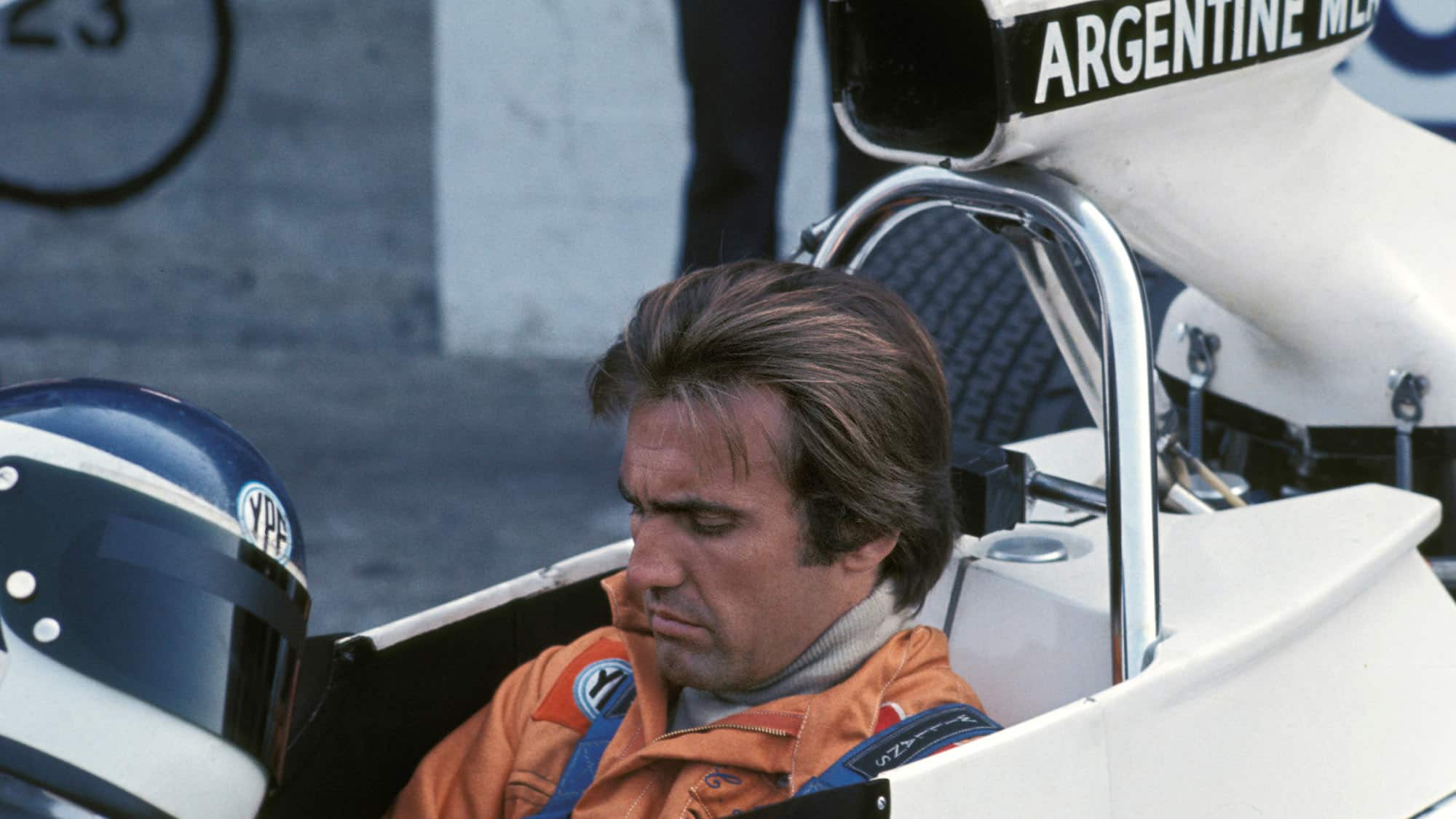

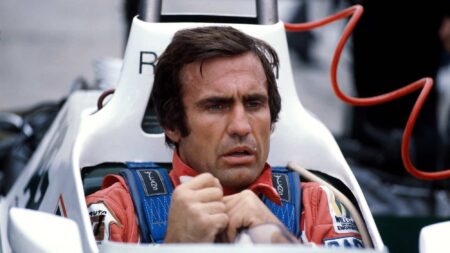

Reutemann and the Brabham BT44B at Paul Ricard in 1975

Grand Prix Photo

It appeared 1975 might be his year and he was certainly more consistent, but only one victory – albeit a memorable one on the Nürburgring Nordschleife – left him in the shadow of Niki Lauda and the magnificent new Ferrari 312T. He and The Rat never got on, and it seems their dislike was rooted long before the summer of 1976, when Carlos – frustrated by Brabham’s new partnership with Alfa Romeo – quit to join Ferrari as replacement for Lauda, who had suffered those terrible injuries at the ’Ring. Lauda had every reason to be furious – with Enzo, not with Reutemann. But of all the people they should sign…

In his book To Hell and Back, Lauda offered a typically unvarnished assessment. “No bouquets for this one. A cold, unappetising character,” wrote Niki of Carlos. “When we were together at Ferrari, we made no bones about it, we simply couldn’t stand each other. It was impossible trying to work with him on the technical side because he would always look for a tactical answer that might conceivably work to his advantage during setting up. After my shunt in 1976 he was something of a problem for me to the extent that he tried to win over the entire Ferrari camp, but I soon settled that. A good driver, but nothing spectacular.”

It sounds like a different man to the one Murray describes. Reutemann himself was non-plussed by Lauda’s plain dislike of him. What was it all about? Murray shrugs. “Niki was quite abrasive, which was fine when you knew him. But Carlos was quiet and he was the new boy on the block from South America, and it was difficult for him. His English in the early days wasn’t brilliant. Mind you, Niki’s wasn’t brilliant either. If a sentence didn’t include ‘shit’ or ‘rubbish’…”

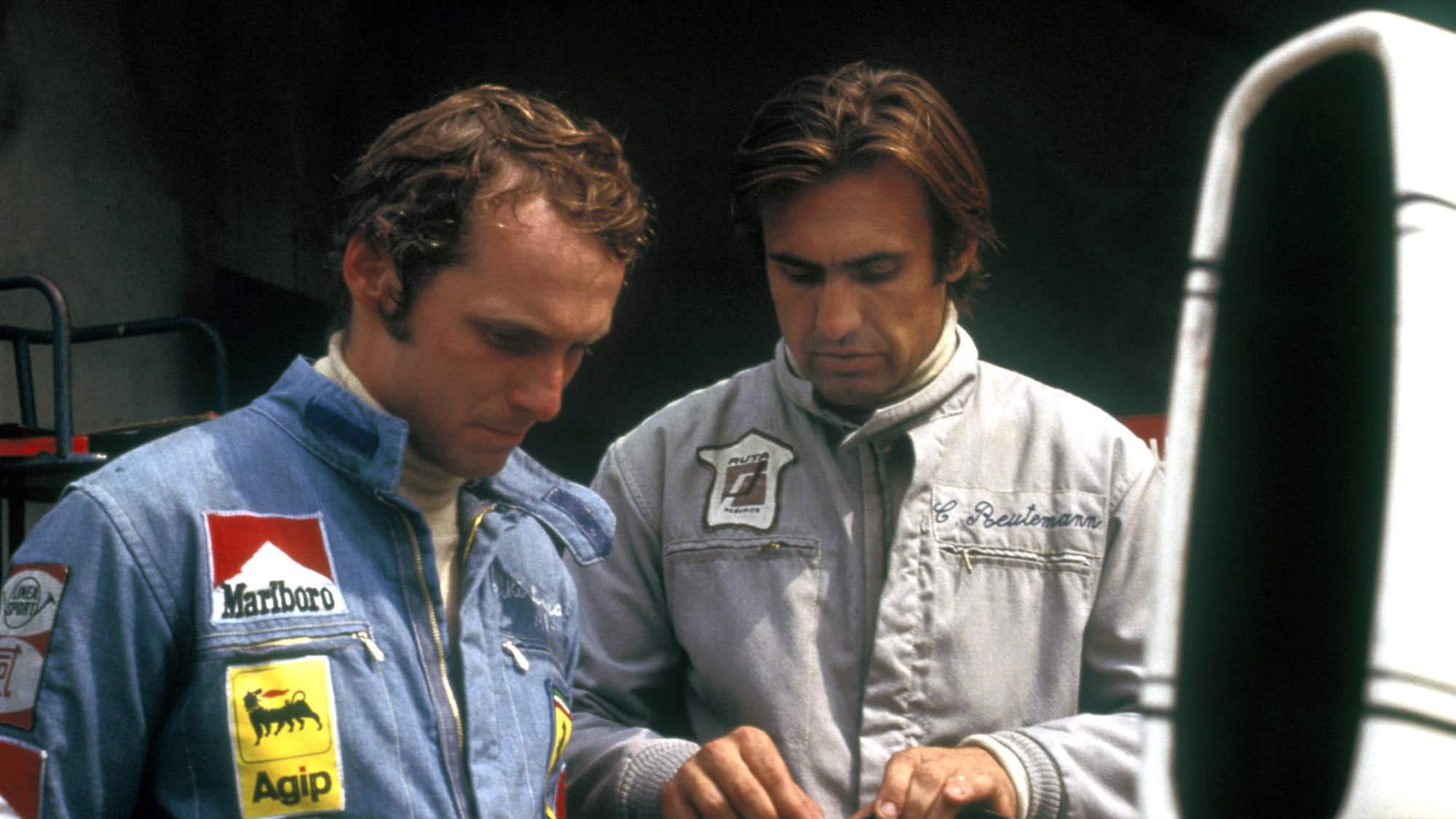

Lauda and Reutemann were never the best of friends even here, at Monza in 1974, before they were team-mates

Grand Prix Photo

Reutemann should have been world champion, of course, late in the day at Williams in 1981. Written off by some as a has-been, he rallied that year to get on top of reigning champion and Williams favourite Alan Jones to head to the Caesars Palace finale a point ahead of Brabham’s Piquet. He stuck the Williams on pole – and then simply disappeared in the race, mumbling something about a handling problem he’d noticed in the morning warm-up. What happened that day remains a mystery, and now he’s gone it always will be.

So any idea why he faded on that day in Las Vegas, Gordon? “No, but I’m glad he did!” comes back the reply. “I don’t know, I don’t think anybody does. Williams said they couldn’t find anything wrong with the car. Carlos always had to be right in his head. Quite often in qualifying he’d say ‘Denny Hulme’s quicker than me, Jackie Stewart’s quicker than me’ or whoever it was and he’d be happy with third. He stopped.”